When Writing Has No Meaning

Edward M. Gómez

Ever since prehistoric cave dwellers first used mineral pigments to craft images of their hands and rudimentary pictographs on their interior walls, humans have been compelled to make and leave their marks.

If the phenomenon of spoken and written language, with its capacity for telling stories and conveying complex ideas, distinguishes humans from other animals, then what are we to make of writing systems that are unrelated to any known language and that, even to informed specialists, make no sense at all? Do such transcribed “tongues” exist?

Such so-called imaginary language is the subject of Scrivere Disegnando, an exhibition of more than 300 works produced by 93 trained and self-taught artists, which is on view through August 23, 2020, at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève in Geneva, Switzerland.

Co-curated by Andrea Bellini, the director of the art center, and by Sarah Lombardi, the director of the Collection de l’Art Brut (CAB), a museum in the nearby city of Lausanne, Scrivere Disegnando (translated by its organizers, from Italian, as “Writing by Drawing”) is the first-ever exhibition produced collaboratively by these two institutions. It brings together works that Bellini and his colleagues borrowed from various collections of modern and contemporary art, along with many loans that have rarely been exhibited before from the CAB, which holds the largest collection of art brut and outsider art in the world.

Scrivere Disegnando opened earlier this year but was forced to close temporarily due to the coronavirus pandemic. It is one of those exhibitions whose accompanying catalogue serves not only as a record of its themes and content, but also expands upon them, becoming a valuable reference in its own right.

Well-illustrated, packed with information about the lives and ideas of the artists whose works are on display in the show, and featuring essays by Bellini, Lombardi, the Swiss art historian Michel Thévoz (who was also the founding director of the Collection de l’Art Brut), and other contributors, Scrivere Disegnando has been published in separate French and English editions.

Imaginary languages — or, more precisely, the representations of such languages — created by artists are, to use one of the catalogue’s buzzwords, “asemic”; they neither possess nor convey any semantic value. They might appear to be made up of “letters” or character strokes, “words,” and “sentences,” but whatever visible forms they might take, they are inherently without meaning, except, perhaps, to their makers.

Indeed, by e-mail, Lombardi observed, “Some of these artists invented imaginary languages and alphabets made up of signs and symbols that are unknown to us; however, they do have a sense or a meaning for their creators.”

Although, she noted, “a certain mystery and strangeness” characterizes these artists’ works, she feels that their imaginary languages are marked by “their own logic” and therefore sometimes appear to be “based on a system that renders them legible” — readable, that is, in ways that demand some imaginative thinking from viewers.

Take, for example, the creations of Catherine Élise Müller (1861-1929), a Swiss woman based in Geneva who, as a spiritualist medium, became known as “Hélène Smith.” In 1891, she attended her first séance, experienced hallucinations, and discovered her paranormal ability.

Between 1895 and 1900, Théodore Flournoy, a psychology professor at the University of Geneva, observed Smith’s automatic writing, trances, and claims about channeling the spirit of Marie Antoinette and being psychically transported to Mars. Smith “wrote” in hitherto unknown languages, including, she said, those of Mars and Uranus. Scrivere Disegnando features her drawings from her psychic voyages and her Martian texts, which Flournoy reproduced in a book he wrote about Smith, which was published in 1900.

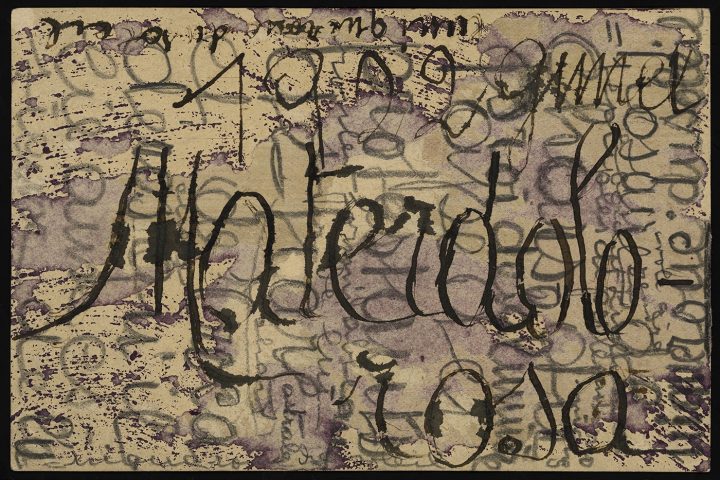

Scrivere Disegnando cites the well-known Swiss art brut creator Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964), who is best known for colorful fantasy images of the court of Wilhelm II, the last German emperor. Here, though, from the Collection de l’Art Brut’s vault comes “Materdolorosa” (1922), an extraordinary ink-on-paper writing-drawing that would feel right at home alongside the experiments in automatism by the Surrealists or certain American modernists on the road to full-blown Abstract Expressionism.

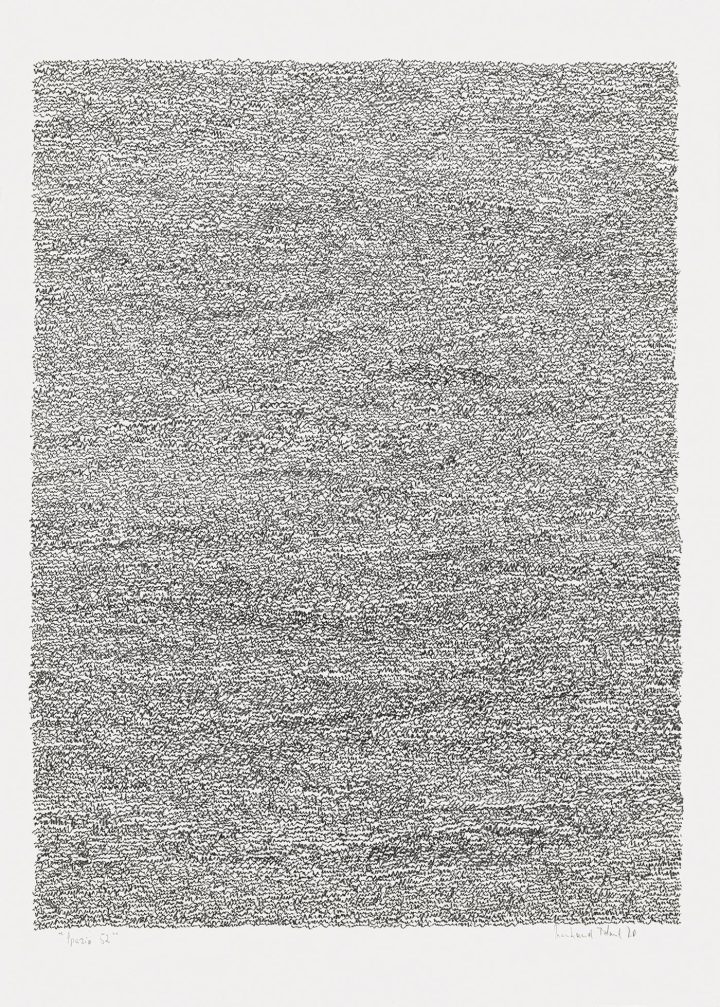

Scrivere Disegnando also examines drawings made by the German artist Irma Blank (born 1934 and based in Italy). Blank is known for her Eigenschriften (1968-72), a series of drawings whose title means “unique scripts” or “private scripts” and consists of sheets covered with dense lines of scrawl without any discernible meaning. The gesture of their making is their elusive semantic value.

In the 1970s, after Blank moved with her husband to Sicily, where she did not speak the language, she produced her Trascrizioni (“Transcripts,” 1973-79), filling the pages of books and newspapers with marks obliterating their printed texts. Joana P. R. Neves, a London-based curator, writes in Scrivere Disegnando that, in these later works, Blank “would push meaning away.” By making them, the artist herself said, she could “forget the world.”

There is more here, including works by the Italian modernist Alighiero Boetti (1940-1994), who moved on from Arte Povera to chart a personal, experimental path. Among other works, he made copy-drawings of Japanese kanji on folded sheets of paper that opened up to explode and render meaningless his written characters.

Like Blank’s Eigenschriften, the peculiar letter-drawings of Justine Python, a Swiss woman who was born in 1879 and whose death date is unknown, cover sheets of paper with densely packed lines of handwriting. They recall the horror vacui, or fear of empty spaces, that characterized the artistic creations of psychotic patients in European psychiatric hospitals, which pioneering researchers examined and attempted to analyze roughly a century ago.

Python, who came from a farming family, felt perennially persecuted, issued stinging recriminations against would-be enemies, and was sent to an asylum. Her letter-drawings, addressed to Fribourg’s “publicprosecutorbossLawyer,” are oddly elegant — and impossible to read.

Scrivere Disegnando examines much more; each artist’s invented language or writing system evokes its own world or provides an unusual bridge to the known world.

By e-mail, Bellini told me, “Our exhibition expresses a paradox: it’s about writing but, in the end, it offers very little to read. To the contrary, it offers a universe to examine, in which one is required to participate with one’s intellect and emotion.” He also noted, “If we look at the history of writing, it has very often been used to hide meaning rather than to make meaning explicit.”

Buried in the various essays in Scrivere Disegnando, a remark by the artist Irma Blank, who is now in her 80s, unwittingly sticks a thumb in Gustave Flaubert’s eye and summarizes the nature and spirit of imaginary language and impenetrable writing systems like her own. “[T]here is no such thing as the right word,” she observed.

And that, as an old American idiom has it, is all she wrote.

Scrivere Disegnando continues at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève (Rue des Vieux-Grenadiers 10, Geneva, Switzerland) through August 23. The exhibition is curated by Andrea Bellini and Sarah Lombardi.

Its accompanying catalogue, Scrivere Disegnando, has been published in separate French and English editions by Skira Editore, in collaboration with the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève and the Collection de l’Art Brut.

hyperallergic.com