VIVRE SOUS LA MENACE

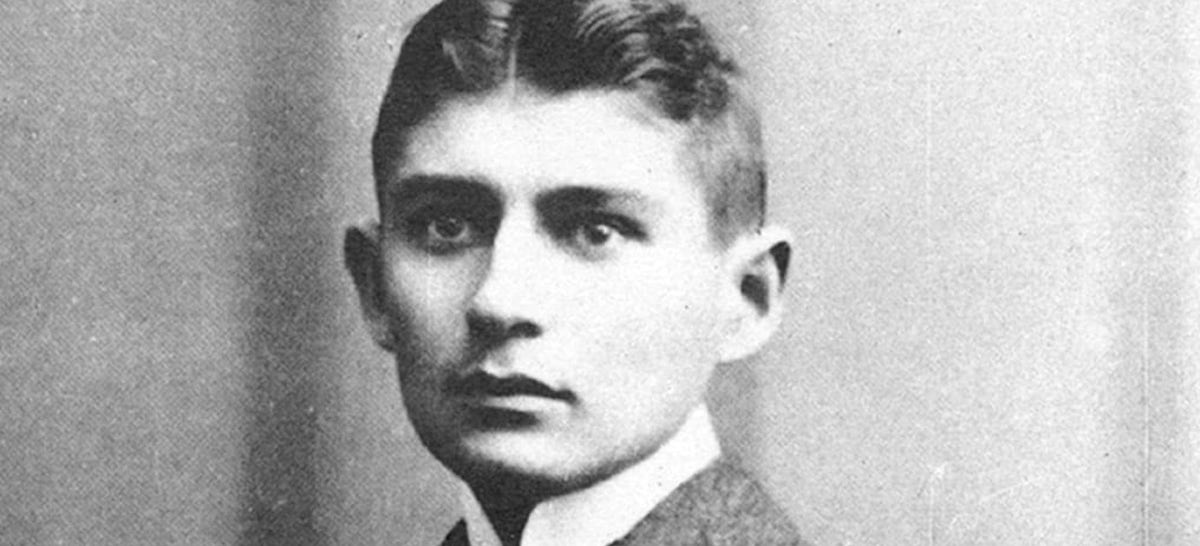

Le Terrier de Franz Kafka

Alain Parrau

« Kafka ne croit guère à la loi, à la culpabilité, à l’angoisse, à l’intériorité. Ni aux symboles, aux métaphores ou aux allégories. Il ne croit qu’à des architectures et à des agencements dessinés par toutes les formes de désir. Ses lignes de fuite ne sont jamais un refuge, une sortie hors du monde. C’est au contraire un moyen de détecter ce qui se prépare, et de devancer les “ puissances diaboliques ” du proche avenir » (Gilles Deleuze et Félix Guattari, Kafka, Editions de Minuit, 1975).

« C’est moi qui ai agencé le terrier, et il semble que ce soit une réussite » [1]. Ainsi débute le récit, sur le mode de la satisfaction du travail accompli que toute la suite du texte va s’acharner à défaire : défaite matérielle (le terrier n’est pas sûr), et défaite du moi qui espérait y trouver un abri définitif. Le récit de Kafka n’est que le déroulement obsédant des réflexions et des émotions suscitées par le terrier dans la conscience de celui qui dit « Je » (animal du genre taupe, blaireau ou renard) : monologue épuisant, ressassement infini où se pressent des constructions mentales de toutes sortes qui relancent chaque fois la pensée. Celle-ci semble ne jamais pouvoir s’arrêter : la menace ne provoque pas la sidération de la pensée, mais son affolement.

Dès le début du récit, le « Je » est livré aux hypothèses qui vont empêcher toute possibilité de repos. Contemplant le grand trou qu’il a creusé pour faire croire qu’il s’agit de l’entrée de son terrier (alors que celle-ci se trouve plus loin, masquée par de la mousse), il est très vite la proie de ce constat désabusé et sans espoir : « Je le sais bien, et c’est à peine si ma vie, même à son actuel apogée, connaît une heure de complète tranquillité ; cet endroit lointain sous la mousse obscure est celui où je suis mortel et c’est souvent que, dans mes rêves, une gueule concupiscente renifle alentour et sans trêve ». Le terrier apparaît déjà comme le lieu où le « Je » peut mourir de mort violente, un futur tombeau ; il faillit ainsi à sa fonction essentielle d’abri et de protection de soi : « je veux que le terrier ne soit rien d’autre que le trou destiné à me sauver la vie, et que, de cette tâche clairement définie, il s’acquitte avec toute la perfection possible […] Seulement, dans la réalité, il assure bien une grande sécurité, mais nullement suffisante ». Cette perfection qui garantirait enfin une sécurité absolue est impossible : la puissance de la menace, en tant que telle, suffit à en interdire l’hypothèse. L’imagination se met à son service pour entamer la possibilité d’échapper à des ennemis invisibles, qui peuvent surgir n’importe où et n’importe quand : « Et ce ne sont pas seulement les ennemis extérieurs qui me menacent ; il en est aussi dans le sein de la terre ; je ne les ai encore jamais vus, mais les légendes en parlent et j’y crois fermement. Ce sont des êtres de l’intérieur de la terre ; la légende elle-même ne saurait les décrire ; même ceux qui en ont été les victimes les ont à peine vus ». Avec ces ennemis légendaires et sans visage la terre elle-même, qui devait constituer une enveloppe protectrice et sûre, est contaminée par la menace, devient source d’une peur immaîtrisable.

Exposé à cette menace invisible, l’esprit avide de repos est condamné au travail épuisant de la pensée qui veut l’identifier, la prévoir et la prévenir, la conjurer pour s’en libérer. Cet épuisement de la pensée et de l’imagination, provoqué par l’attente de ce qui va certainement arriver mais n’arrive toujours pas, ne pourrait cesser qu’avec l’apparition de l’ennemi, le combat victorieux contre lui « pour qu’enfin – ce serait l’essentiel – je sois à nouveau dans mon terrier, tout disposé cette fois à en admirer même le labyrinthe, mais d’abord à tirer sur moi le couvercle de mousse et à me reposer, je crois, pour tout le temps qui me reste à vivre ! ». Tant que cet ennemi ne surgit pas, ne devient pas enfin visible (et, dans le récit, il ne surgira pas) la pensée se nourrit de cette attente anxieuse, se déploie avec toute l’énergie sans limites que libère l’absence de son objet réel.

La pensée insomniaque

Ce régime infernal de la pensée est intimement lié au sommeil, parce qu’il provoque l’impossibilité de dormir, ou l’interruption angoissée du sommeil. Au début du texte, pourtant, le sommeil semble encore le plus fort. Ayant aménagé dans le labyrinthe de son terrier des petites places rondes destinées au repos, le « Je » affirme : « Je dors là du doux sommeil de la paix, du désir calmé, du but atteint, de la propriété de ses propres murs ». La crainte du danger le réveille certes plusieurs fois, mais ces réveils ne se prolongent pas en une vigilance inquiète, au contraire : « Je ne sais si c’est une habitude héritée de temps anciens, ou bien si, même en cette demeure, les périls sont suffisamment forts pour m’éveiller : régulièrement, de temps en temps, j’émerge avec effroi d’un profond sommeil et je tends l’oreille, j’épie ce silence qui règne immuablement jour et nuit, je souris rassuré et, les membres détendus, je plonge dans un sommeil encore plus profond ». Dormir dans un abri sûr, ce désir lié à l’enfance et à son besoin de protection semble assuré par le terrier à son constructeur [2]. Parce que ce que le terrier « a de plus beau, c’est son silence ». Constatation immédiatement relativisée par une phrase qui annonce « le sifflement à peine audible » lequel, au milieu du récit, va définitivement rendre ce sommeil apaisé impossible : « certes, ce silence est trompeur ; il peut être interrompu tout d’un coup, et ce sera la fin ».

Une autre occurrence de ce sommeil profond apparaît ailleurs. Cette fois-ci, il n’est plus garanti par le silence, mais par un rêve, celui d’une construction parfaite de l’entrée du terrier qui le rend « imprenable » : « le sommeil où me viennent de tels rêves est le plus doux de tous ; des larmes de joie et de délivrance brillent encore à mes moustaches quand je m’éveille ». Le rêve surgit du plus intime du « Je » pour protéger le sommeil, il enveloppe le rêveur d’images rassurantes qui naissent du plus profond de lui-même et se répandent en lui comme un baume délicieux. Qu’elle vienne de l’extérieur (le silence) ou de l’intérieur de soi (le rêve), le sommeil a besoin de cette garantie pour être possible, il ne peut pas compter uniquement sur ses propres forces. Il apparaît donc comme une expérience fragile et incertaine, lorsqu’il est exposé à une menace, réelle ou imaginaire. Le récit de Kafka témoigne aussi de cette fragilité essentielle. On retrouve celle-ci dans les expériences où la violence du pouvoir veut détruire le plus intime de l’individu, dans les camps de concentration par exemple. Lisant le chapitre intitulé « Nos nuits » du livre de Primo Levi, Si c’est un homme, Pierre Pachet écrit ces lignes si justement accordées à ce que décrit Kafka : « La faculté de s’aménager des entours habitables est animale ; est humaine, en revanche, la suranimalité qui fait survivre cette faculté quand elle est contrainte à cohabiter avec la pensée – propre à l’homme, celle-là – qu’il n’y a plus de paix possible. La pensée est éminemment humaine, on le sait bien ; la dépasse pourtant en humanité le simple désir de dormir, de dormir avec la pensée d’un homme terrifié. Le nazisme vise cela ; il ne vise pas que la liberté de la pensée ; ou plutôt, s’il veut l’atteindre, c’est à travers le tiède, le tendre désir de dormir [3] ».

Protecteur du sommeil, le rêve peut pourtant trahir le rêveur, se mettre au service de la menace : lorsqu’il devient le cauchemar de cette « gueule concupiscente qui renifle alentour et sans trêve », ou celui de la certitude effrayante de l’imperfection du terrier : « Plus terrible est l’impression que j’ai parfois, généralement en me réveillant en sursaut, que la répartition en cours est une erreur totale, qu’elle est susceptible d’entraîner de grands dangers et qu’il faut de toute urgence la rectifier, sans égard pour ma fatigue et mon envie de dormir ; alors je me précipite, je vole, je n’ai pas le temps de me livrer à des calculs ». Le réveil, ici, n’est plus suivi d’un sommeil profond et paisible : avec lui commence une veille qui voudrait ne jamais s’interrompre, une vigilance qui aimerait pouvoir supprimer le sommeil. La menace fait surgir une puissante volonté insomniaque qui s’empare du « Je » et l’assujettit : il faut que la conscience reste toujours en éveil, aux aguets, car lorsque « c’est moi qui dors, veille celui qui veut ma perte ». Dormir, c’est s’abandonner à la vigilance de l’ennemi, se livrer à elle. La passivité absolue du dormeur en fait déjà une proie offerte, sans défense.

Cette volonté insomniaque est exacerbée par la nécessité d’une surveillance permanente de l’entrée du terrier, qui seule pourrait en assurer une défense efficace. Le « Je », alors, voudrait pouvoir sortir de soi, s’extraire de lui-même pour se dédoubler, devenir à la fois celui qui veille et celui qui dort. Fantasme d’une conscience toujours vigile, qui protégerait simultanément l’entrée du terrier et le sommeil de son habitant. L’imagination surmonte le besoin indispensable de dormir par un scénario fantastique, à l’attrait irrésistible : « Je me cherche une bonne cachette et je surveille l’entrée de ma demeure – cette fois de l’extérieur – des jours et des nuits durant. On peut dire que c’est insensé, mais cela me cause une indicible joie, mieux encore, cela me tranquillise. J’ai alors l’impression d’être non pas devant ma maison, mais devant moi-même pendant mon sommeil, comme si j’avais la chance de dormir profondément et de pouvoir en même temps me surveiller intensément ». Ailleurs dans le texte, le désir de surprendre l’ennemi est tel que le « Je » se dédouble à nouveau, il devient à la fois celui qui surveille et l’animal prêt à s’introduire dans le terrier : « Je ne m’écarte plus, même extérieurement, de l’entrée ; patrouiller en rond autour d’elle devient mon occupation favorite ; c’est déjà presque comme si c’était moi l’ennemi et que j’épiais l’occasion favorable pour réussir à m’y introduire par effraction ». Le dédoublement de soi est la seule « solution » qui s’offre à l’habitant du terrier, que l’impossibilité de faire confiance à quiconque condamne à une solitude absolue : « Si seulement j’avais je ne sais qui sur qui compter, que je puisse poster en observation à ma place, alors je pourrais assurément descendre le cœur léger […] Mais de l’intérieur du terrier, donc d’un autre monde, faire confiance à quelqu’un d’extérieur – je crois que c’est impossible ».

Prisonnier du mouvement incessant de sa pensée, qui le précipite dans des modifications de l’organisation du terrier toujours insatisfaisantes, le « Je » intériorise à ce point la menace qu’il semble, par moments, devenir une menace pour lui-même, au bord d’une folie de la pensée qu’il ne maîtrise plus et dont il est la proie. Il se révèle littéralement traversé par un fonctionnement mental qui le submerge. La pensée insomniaque, alors, brouille la distinction de la veille et du sommeil, ouvre l’espace d’une expérience ambiguë où les repères de la réalité se troublent. Évoquant à nouveau ses multiples travaux d’amélioration du terrier, le « Je » conclut : « Tout cela métamorphose ma fatigue en agitation et en zèle, c’est comme si, pendant l’instant où j’ai pénétré dans le terrier, j’avais fait un long et profond somme » [4].

Le « sifflement » de la menace

A peu près au milieu du texte, le sommeil de l’habitant du terrier est interrompu par le bruit ténu d’un sifflement : « J’ai sans doute dormi très longtemps ; je n’émerge que du dernier sommeil, celui qui déjà se dissipait de lui-même ; mon sommeil doit déjà être très léger, car c’est un sifflement à peine audible en lui-même qui me réveille ». Pour le sommeil de celui qui se sait menacé, le moindre bruit peut être signe d’un danger, provoque le réveil et la vigilance. A partir de ce moment, toute l’activité mentale de la conscience va se concentrer sur ce sifflement : déterminer l’animal qui le produit, localiser le bruit, le supprimer. La menace n’a pas enfin un visage, mais un son, sur lequel vont se fixer toutes les hypothèses, tous les plans de l’habitant du terrier. La pensée insomniaque devient la proie du sifflement [5].

Ce sifflement, le narrateur croit pouvoir immédiatement en identifier l’origine : il est provoqué par un passage creusé par les « petites bestioles », qu’il a « beaucoup trop peu surveillées et beaucoup trop épargnées » jusqu’à présent. L’inquiétude suscitée par ce bruit ne débouche alors que sur un plan d’action efficace et rationnel : « Il faudra que je commence, en auscultant les parois de ma galerie, par localiser l’avarie grâce à des sondages, et ensuite que je supprime ce bruit ». Plan dont l’objectif final est l’anéantissement des « petites bêtes » : « Aucune ne devra être épargnée ». L’imagination se donne ici un adversaire taillé sur mesure : rien à voir avec les « ennemis légendaires » qui infligent une mort si rapide que leurs victimes les ont à peine vus, ou avec l’inquiétante « gueule concupiscente » qui renifle autour de l’entrée du terrier. Les « petites bêtes » semblent d’abord pouvoir conjurer la menace en lui offrant l’incarnation la plus rassurante. Mais le travail de recherches et les quelques sondages effectués par le « Je » pour localiser le sifflement se révèlent très vite sans résultat. Non seulement le bruit persiste, mais il donne l’impression de venir de partout à la fois : « Mais c’est justement cette uniformité en tous lieux qui me trouble le plus, car elle est incompatible avec mon hypothèse de départ ». Le plan efficace et rationnel va se défaire avec la persistance et l’impossibilité de localiser le sifflement ; celui-ci, peu à peu, ruine toutes les explications imaginées par l’habitant du terrier. L’hypothèse des petites bêtes est abandonnée pour laisser la place à une autre, bien plus inquiétante : « Mais peut-être – cette pensée aussi s’insinue en moi – s’agit-il d’un animal que je ne connais pas encore ». Un animal qui, un peu plus loin, est imaginé « gros » et travaillant « à une vitesse folle ».

Reprenant ces petits sondages aléatoires dans les parois de son terrier, le « Je » ne peut que constater qu’ils ne mènent à rien, et que l’anxiété qui le pousse à ces travaux désordonnés l’épuise, le plonge dans un état quasi somnambulique : « Plus d’une fois déjà, je me suis pour un moment endormi au travail dans quelque trou, une patte levée et crispée dans la terre que, à demi endormi, je m’apprêtais à arracher ». Un nouveau plan s’impose, « bâtir dans les règles une grande tranchée en direction du bruit », « plan raisonnable » qui suppose d’abord que le « Je » répare les dégâts occasionnés par ses précédents sondages, comble les trous qu’il a lui-même creusés dans les parois. Mais ce travail, l’habitant du terrier, à bout de forces et hanté par la persistance du sifflement, n’arrive pas à le réaliser, alors même qu’il savait l’effectuer, assure-t-il, d’une « façon inégalable » : « Mais cette fois, j’ai du mal ; je suis trop distrait ; sans cesse, en plein travail, j’appuie l’oreille à la paroi et j’écoute, et je laisse avec indifférence la terre que j’ai ramassée retomber en ruisselant dans la galerie au-dessous de moi ».

La menace décompose toute forme de rationalité, théorique ou pratique, qui s’efforce de la prévenir et de la conjurer. Elle retourne les efforts du « Je » contre lui-même, fait de l’écoute une véritable torture : « Et que de temps, que de tension exige cette longue écoute de ce bruit intermittent ! ». Elle révèle un régime de la pensée qui l’emporte au-delà d’elle-même, dans une fuite en avant sans fin. Avec elle la conscience devient, non plus l’abri d’une liberté ou d’un « bonheur » (celui de se laisser aller à ses pensées les plus spontanées), mais un instrument de supplice : « Mais à quoi bon tous ces rappels au calme : l’imagination galope, et je ne démords pas de l’idée – inutile de vouloir se l’ôter de la tête – que le sifflement provient d’un animal, non pas de nombreux petits animaux, mais d’un seul, et gros ». Avec le renforcement du sifflement c’est encore l’imagination qui installe, peu à peu, dans la conscience de l’habitant du terrier, la certitude angoissante de son encerclement : « Il a bien dû déjà, autour de mon terrier, parcourir quelques cercles, depuis que je l’observe. Et voilà maintenant que le bruit se renforce bel et bien, que les cercles par conséquent se rétrécissent ». Cet encerclement provoque alors une forme de déploration : le « Je » se reproche son « insouciance puérile », d’avoir négligé tous les avertissements, de ne s’être préoccupé que des « petits dangers » en oubliant « de penser réellement aux dangers réels ». Vaincue par la puissance du sifflement la conscience ne peut plus, alors, que se raccrocher à une ultime rêverie rassurante, dernière et dérisoire protestation contre la violence qui lui est infligée : « Certes, l’animal semble très éloigné ; s’il s’éloignait ne fût-ce qu’un peu davantage, sans doute le bruit disparaîtrait-il ; peut-être alors que tout pourrait s’arranger comme au bon vieux temps ; ce ne serait plus alors qu’une mauvaise expérience, mais bénéfique, elle m’inciterait aux améliorations les plus diverses ».

Evoquant « la métamorphose en ce qui est petit » si fréquente dans les textes de Kafka, et en particulier celle en petits animaux, Elias Canetti l’interprète comme un moyen « d’échapper à la menace en devenant trop insignifiant pour elle » [6]. Le Terrier peut être lu comme l’échec de cette tentative. Impossible, face à la menace, de trouver un abri, ni dans la pensée, ni dans la réalité extérieure. De cette expérience si proche de ce qui a été vécu (et l’est encore dans certains pays) par des hommes exposés à la terreur, le récit de Kafka offre une préfiguration saisissante. Mais ne garde-t-il pas aussi la trace du cataclysme que fut la première guerre mondiale ? Les galeries, les boyaux sans cesse creusés dans Le Terrier évoquent les tranchées, dans lesquelles des millions d’hommes ont fait l’épreuve d’une nouvelle forme de guerre. Les conditions extrêmes de cette guerre ont révélé un rapport des combattants à la terre sans précédent : « Pour personne, la terre n’a autant d’importance que pour le soldat. Lorsqu’il se presse contre elle longuement, avec violence, lorsqu’il enfonce profondément en elle son visage et ses membres, dans les affres mortelles du feu, elle est alors son unique ami, son frère, sa mère. Sa peur et ses cris gémissent dans son silence et dans son asile : elle les accueille et de nouveau elle le laisse partir pour dix autres secondes de course et de vie, puis elle le ressaisit – parfois pour toujours » [7]. Creuser, s’enfouir dans la terre pour se protéger d’une menace de mort anonyme, sans visage, annoncée par les bruits des différents obus et projectiles fut le quotidien de la plupart des combattants du front. Abri provisoire et fragile, la terre est aussi, comme dans le récit de Kafka, matière dangereuse, annonciatrice de mort, linceul ou tombe. Roland Dorgelès rapporte, dans Les Croix de bois, l’effroi provoqué par le bruit sourd des pioches des Allemands qui creusent, sous la tranchée, une galerie pour y installer une mine. La menace qui venait du ciel naît soudain du cœur de la terre elle-même : « Nous prîmes la veille. Les obus tombaient toujours, mais ils faisaient moins peur à présent. On écoutait la pioche » [8] ; « Tous assis sur le bord de nos litières, nous regardions la terre, comme un désespéré regarde couler l’eau sombre, avant le seau. Il nous semblait que la pioche cognait plus fort à présent, aussi fort que nos cœurs battants. Malgré soi, on s’agenouillait, pour l’écouter encore » [9] . Comme le sifflement du terrier, les coups entendus dans la tranchée signent cette condition nouvelle de l’homme : nul abri sûr pour lui, désormais.

Ne reste peut-être, alors, que la compassion pour l’être sans défense exposé à la menace, l’accueil muet de sa fragilité et de sa détresse. Dans une lettre à Max Brod datée de 1904, Kafka écrit : « Telle la taupe, nous nous frayons une voie souterraine et nous sortons tout noircis, avec un pelage de velours, de nos monticules de sable écroulés, nos pauvres petites pattes rouges tendues en un geste de tendre pitié » [10].

Alain Parrau

[1] Franz Kafka, Le Terrier (Der Bau) traduction de Bernard Lortholary, Garnier-Flammarion, 1993, p.125. Ce récit inachevé, rédigé à Berlin pendant l’hiver 1923-1924, est le dernier des textes inédits de Kafka. Il sera publié une première fois par Max Brod en 1931. Le champ sémantique du mot allemand Bau est large : il désigne le terrier des petits carnassiers, mais aussi toute activité de construction ou n’importe quel édifice qui en résulte.

[2] Dans son livre L’Autre Procès, Elias Canetti écrit, à propos de Kafka (qui souffrait d’insomnies) : « Il y a chez lui une sorte d’adoration du sommeil, il le considère comme un remède à tous les maux, ce qu’il peut recommander de mieux à Felice quand l’état de cette dernière l’inquiète : « Dors ! Dors ! ». Le lecteur lui-même ressent cette exhortation comme un envoûtement, une grâce divine » (L’Autre Procès, Gallimard, 1972, p.39).

[3] Pierre Pachet, La Force de dormir, Gallimard, 1988, p.26.

[4] Ce brouillage de la distinction veille/sommeil, réalité/rêve, peut être rapproché de la « condensation du réel et du fantastique » caractéristique, selon Claude Lefort, du totalitarisme, un régime politique où la terreur, la surveillance dont chacun se sent l’objet et la méfiance mutuelle qui en résulte, aboutissent à ce que « nul n’est sûr d’être à l’abri dans son lieu propre ».

[5] Dans les expériences réelles des sujets exposés à la terreur, ce sont d’autres bruits qui incarnent la menace : celui de l’ascenseur, la nuit, dans les mémoires de Nadejda Mandelstam (les arrestations avaient lieu le plus souvent la nuit), celui des voitures de la Gestapo dans le Journal de Victor Klemperer.

[6] Elias Canetti, L’autre procès, op. cit., p.113.

[7] Erich Maria Remarque, A l’Ouest rien de nouveau, Le livre de poche, 1992, p.57.

[8] Roland Dorgelès, Les Croix de bois, Le livre de poche, 1972, p.215.

[9] Ibid., p.219. Ce sont les soldats de la relève qui seront victimes de cette mine.

[10] Citée par Elias Canetti, L’Autre Procès, op.cit., p.114.

paru dans lundimatin#310, le 26 octobre 2021