Get Lost in a Corn Maze That Looks Like a Microscopic 'Water Bear'

by Jessica Leigh Hester

August 12, 2020

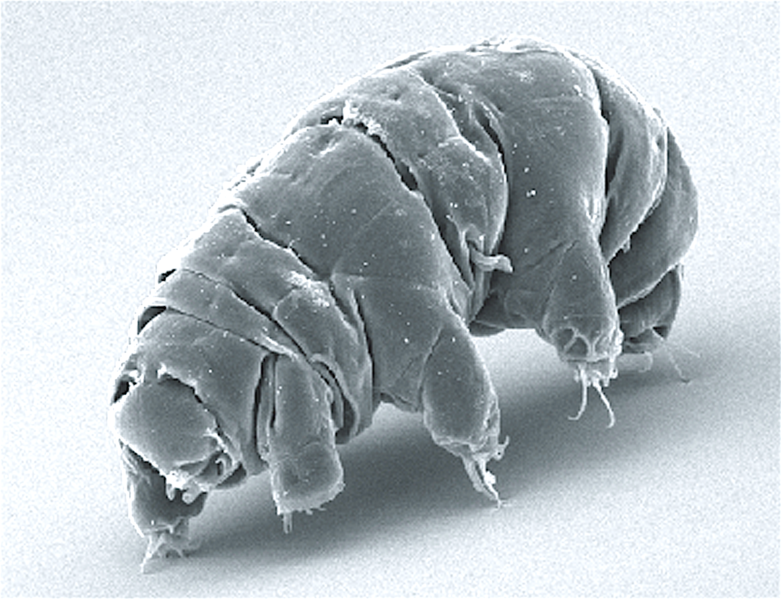

When Angie Treinen first learned about

tardigrades a few years ago, at a family-friendly science event at the

University of Wisconsin, she couldn’t believe it. She loved their

squashed little faces and their wonderfully rotund bodies, which look

like a puffy stack of partly melted marshmallows. “I just stood there

the whole time like, ‘Are you kidding me?’” Treinen says.

Treinen studied zoology

and worked as a veterinarian, but had never encountered teeny tiny

tardigrades, which are variously known as moss piglets and water bears.

Immediately, they captivated her. Typically less than a millimeter long,

tardigrades thrive in both mundane and extreme conditions, including

bone-rattling icy landscapes, oceans, and ultra-hot environments.

(They’re probably flourishing near your house, too, and it’s easy to meet them.)

Internet audiences love them because they’re endearingly goofy, like

claymation creatures loping around on impossibly spiky claws.

Researchers, meanwhile, are fascinated by their ability to stay alive: Tardigrades persist in the face of pressure changes, temperature fluctuations, and vanishing water and oxygen.

So when Treinen sat

down to plan out the annual corn maze for the eponymous farm she owns

with her husband in Lodi, Wisconsin, it seemed obvious. 2020, a year of

disease, economic recession, and crushing ennui, would be the year of

the tardigrade. Treinen talked to Atlas Obscura about designing, planting, sculpting, and welcoming visitors to the 15-acre corn maze, which is open at Treinen Farm through November 8, 2020.

What makes for a good maize maze?

We have a lot of parameters. It typically

needs to be a story, or something really intriguing—we’ve done Aesop’s

fables and some Greek myths, like Icarus. It has to be a recognizable

figure: When the picture of the maze is online, I don’t want people to

be confused, like “What is that?” But I try to do a completely different

art style each year. We did a Picasso-sketch style one year, and Art

Nouveau another. Sometimes it looks like stained glass; sometimes it

looks like folk art. I don’t want my mazes to all look exactly the same.

I’m also aware of what is challenging for visitors to navigate in the

maze. I want people to get lost, and I want there to be a lot of

challenge—but not so much that people are like, “I’m outta here and I’m

never coming back.”

How do you design them?

I fill up my Pinterest page with

interesting things, and then I start sketching by hand—just rough, rough

sketches so that I have an idea what the main figure and layout might

be. Then I do almost all of it in Illustrator. My ultimate product is a

black-and-white line drawing.

How does maze design affect the planting?

My husband plants the field

in vertical and horizontal rows, which is not how you normally grow

corn. But he does this so there’s literally a grid growing right into

the field, with each row about 30 inches from the next, so it becomes a

dense field. When I am done with the design, I put a grid on a layer in

the Illustrator, which matches the grid he’s planted in the field.

The design typically takes me about 10

days. I start in June, on the day that the corn goes in. Ten days is the

time between when you plant the corn and the time it’s going to be up

in visible rows—and if the weather’s warm, it comes up even faster. You

have to cut the corn while you can still see what the rows are. Once it

gets to be about knee-high, the leaves of the corn are starting to

overreach, and you can’t distinguish the rows anymore. So that’s the

deadline. One year it came up in six days, and my husband was like, “The

corn is up. I need the design.” I need that pressure.

How do crews go in and make the maze?

I print the plans out and

give them to the maze-cutting crew. They’re able to find a point on my

plan and then, by counting rows, they put stakes and flags out and find

the corresponding parts in the field. They paint where the trails need

to be, and they mow them first before tilling the fields [and ripping up

the roots]. We have a commercial mower about five feet wide. If there’s

a mistake when you mow the corn, it’ll grow right back (and I can

usually alter the map to match the mistake). It takes about 120 to 150

person hours to cut the maze. Periodically, I take my drone up to verify

things are looking ok.

The maze crew loves it when there’s a lot

of circles or parts of circles, because circles are easy to cut. I can

mark on the design the center of the circle and the radius. Somebody

stands at the center, takes a measuring tape, pulls it out to the

radius, and then just walks around in a circle. Anything geometric is

also easy for them to cut, because of the clear angles. Art Deco

borders, or specific flourishes which need to be precise, they get a

little complain-y about those things. But they always do it just fine.

This year, the maze is more organic. All of those paths are not set in

stone.

What’s the experience like for a visitor? Will they have any sense that they’re exploring a tardigrade?

The corn is about 10 feet tall now. The

only way you can see the tardigrade is to be up in the air. We have a

tower that you can walk up and overlook the maze, but you can’t really

see the design—just some of the swirls. You have to be up in an airplane

or use a drone to really see it. What the visitors are seeing is

corridors of corn that all look the same, basically.

You’ve done other science mazes in the past, such a trilobite, Wisconsin’s state fossil, in 2017. What appealed to you this year about tardigrades?

This year, when I was designing the maze,

I was anxious, as everybody else probably was, too. I didn’t know what

the future was going to be. I didn’t even know for sure if we were going

to be able to open our business at all. But my husband said, “You know

what, we’re going to put all the pumpkins in, we’re going to put the

maze in. We can’t do it if we don’t have those things.” I was thinking

how resilient water bears are. I mean, come on. That has to be the 2020

corn maze. A lot of people said to me, “Oh, why don’t you do a virus?”

I’d like to be a place where people don’t have to think about it for two

hours. But I did want to acknowledge that it’s really hard right now.

How does a maze made of living corn change over the course of its run?

Right now, the corn is as tall as it’s

going to be. But even after it stops growing vertically, it grows these

tassels, which hold pollen. Then the pollen falls where the ears are

going to be, and then the ears grow. The most important thing is that

the corn stalks be really strong and that the leaves stay green for as

long as possible, because when they dry, they get brittle and kind of

break, and then your maze looks really sparse. Ours will get killed by

the frost around the beginning of October. By the end of the season,

it’s brown. Eventually, we harvest it and sell it [typically for animal

feed].

This year’s maze recently opened to the public. How have visitors reacted so far?

One of the first people

who came in had a tardigrade tattoo. That is honestly one of the most

amazing things I’ve seen in a really long time. The visitors we’ve had

so far really want to talk about tardigrades; they’ve gone to our

website and clicked on all the links and learned about them. Somebody

said they had found tardigrades and had a microscope and were taking

care of them. I thought, “Wow, okay, I think I probably need to do

that.”