For These Young Street Artists, Amman Is a Beige Canvas

Color, community, and empowerment are enlivening Jordan’s capital.

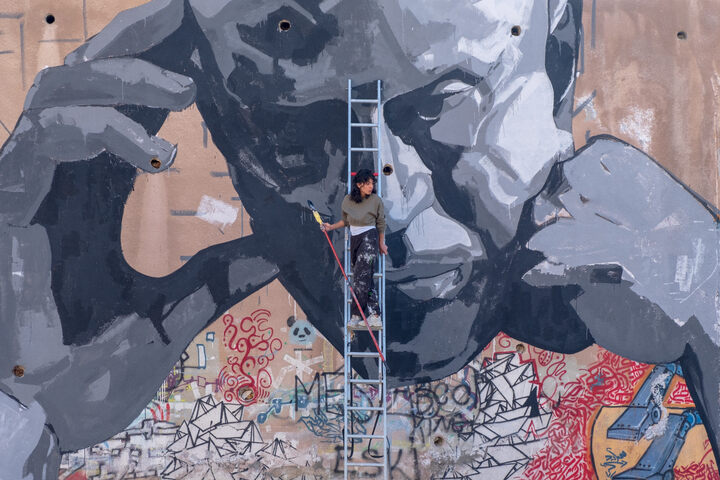

Miramar Al Nayyar, a 23-year-old émigré from Iraq, is at the forefront of a burgeoning art scene. Mohammad Emad

Passerby in secondhand overcoats scattered to

get out of the rain as dusty Parisian songs mingled with old favorites

from Lebanon and Egypt at a fashionable café in Amman’s Jabal Luweibdeh.

The district is popular with expats and home to a large portion of the

city’s cultural centers, coffee houses, pastry shops, and bars.

This café is usually a hipster hive,

filled with large beanies, oversized glasses, and pricey lattes, plus a

nice staff, well-watered plants, and a couple of stray cats. But on a

cold Monday night in January, the biting rain had chased most everyone

away.

Though not quite everyone: Miramar Al

Nayyar, a 23-year-old artist, dawdled at a pub table behind the barista

bar, smoking cigarettes, discussing the city’s changing art scene, and

describing her life with humor and candor.

She spoke about her family, and how they

fled Iraq in 1992, when government officials targeted her father for

forging documents used to get imprisoned communists out of jail. She

spoke about her decision to drop out of college and pursue art full

time. And she spoke about emotion, philosophy, and the fundamentals of

art, as her eyes wandered in search of words to describe it all.

Al Nayyar and a small community of

untrained street artists are at the forefront of a burgeoning art scene

in Amman—one that exists outside the traditional galleries that dot

Jabal Luweibdeh and other districts like it.

Traditionally, the galleries here have

been reserved for “specific” kinds of people, according to Al Nayyar.

That is to say, those who can afford to buy paintings to fill their

homes. In Jordan, where wages are low and unemployment is high, art usually has little place in the day to day struggle to put food on the table.

Founded on seven hills, or jabals,

Amman has swelled in size and population over the last century. When

the city was chosen as the new capital of Jordan, in 1921, it had about

5,000 residents. But in 1948, in the wake of the Arab-Israeli war, wave

after wave of refugees began to arrive here. Now more than four million

people call Amman home.

As the city’s population ballooned,

so too did the area it encompassed, swallowing and integrating

Palestinian refugee camps that were once outside the city limits, and

triggering a building boom to accommodate all the new residents. In

response, Amman’s civic planners erected a patchwork of cheap concrete

and sandstone buildings, which today snake up the city’s hills and into

its valleys like discarded cardboard boxes, arrayed in no obvious order.

The word “drab” has long been used to describe the city’s facade.

But lately that has started to change.

The influx of immigrants from different countries has included artists

from Iraq, skilled carpenters and tradesmen from Syria, and educated

Palestinians. All of that mixing and mingling has birthed an unofficial

citywide rejuvenation project that began over a decade ago and has

accelerated in the past five years. Vibrant murals and graffiti—some

sanctioned by the city, some not—have popped up on walls across Amman

like spring flowers peeking through cracks in the pavement.

Bright pops of color—blues

and pinks, yellows and greens, reds and oranges—now adorn the city’s

shabby stairs, metal doors and shutters, and sides of apartment

buildings and alleyways, forming striking portraits of robots and cats,

cartoons and calligraphy, poems and quotations.

Crowded markets, or souqs, and

Roman ruins—the city’s traditional tourist draws—have started to share

the spotlight with street art, creating a new cottage industry for independent artists

and organizations that are centering tours around murals and graffiti,

and that receive commissions from private businesses to beautify walls.

“The art tours have been really

interesting,” says Hind Joucka, a 27-year-old art consultant, who leads

tours herself and founded an online platform for local artists called Artmejo.

“They’re lots of fun, and there’s been this extra level of

communication between people coming to visit and really finding out

about the [city’s modern] culture.”

To Joucka, the trend is a

boon for residents and visitors alike. “You’re beautifying the city,

you’re adding a bit of color,” she says. “Everyone says Amman is a beige

color, and now it’s no longer that.”

Every day, she says, it seems like a new

mural or work of graffiti appears. Walk around long enough and you’ll

see the names Rain, Wize One, and Siner frequently tagged on walls

across the city. And murals are cropping up so fast that the Amman Street Art Documentation Project, a map dedicated to tracking them, has had trouble keeping up.

The municipal government seems to have

taken notice, and in 2013, after years of indifference to public art, it

approved a new street-art festival called Baladk. Founded by the community-focused Al Balad Theatre,

Baladk functions as a giant citywide workshop each year, bringing

international talent to Amman to partner with local artists to paint

murals.

Beyond the festival,

however, getting permission from the city to paint on public walls can

still mean a lot of red tape. Amman remains a conservative place, and

officials worry about offending religiously orthodox communities, where

subjects such as homosexuality and gender-based violence remain taboo.

For a recent public-art project called “Breaking The Silence,”

organized in part by Joucka and aimed at female empowerment, officials

seemed wary to grant permission upon learning that an eight-story mural,

painted by Al Nayyar and 22-year-old Dalal Mitwally, would feature a

woman.

“The people I was working with were a

little bit accepting of things,” says Joucka. “But at the same time they

would be like, ‘Oh, I have to see the picture. I have to see the woman.

We heard it was a female picture, so we need to know.’”

Mitwally painted her first

mural with Baladk in 2018. She now works part time at a cultural

foundation tucked away in Jabal Amman, another neighborhood dotted with

art galleries. Surveying the city’s chaotic downtown and rolling hills

of concrete from the foundation’s library, she says, “I think we as a

community … have [a] problem with our visual taste. I feel like [Amman]

is very gray and drab—beige even.”

Public art is starting to address that

aesthetic problem, and gender disparities too. Most of the street

artists in Amman are women, says Mitwally. When they paint a new mural,

residents often gather around them, watching them work. It speaks to the

communal nature of street art, and of murals in particular. It also

helps chip away at entrenched notions of what women can and can’t do.

“It’s … this interactivity with the

public that’s so unique,” says Mitwally. “You have kids walking around

and asking to help. You have old ladies passing by and just saying, ‘Yatik al afia’ [Arabic for ‘May God give you good health’] and offering you tea.”

This gives artists a chance

to talk directly to residents, and to listen to their stories in a way

“you don’t really have a chance to do unless you go knocking on their

doors and say ‘I want to get to know you.’”

Mitwally painted her first mural in

Hashmi Shamali, a low-income neighborhood that houses a Palestinian

refugee camp. Baladk has commissioned at least half a dozen murals in

the area, and residents now gladly direct tourists who are looking to

capture photos of some of Amman’s vibrant artwork.

“If it wasn’t for the art,” says

Mitwally, “they wouldn’t be that welcoming to the foreigners that pass

by. But they are very welcoming at this point, so [the art has] created

this openness.”

But Mitwally, like Al Nayyar, says that in some ways the city’s alfresco art scene, though changing, isn’t exactly new.

“[Amman’s street art] is very underrated,

I feel, because … if you pass by school walls, you find all these

quotes by these kids [written with] household spray cans … regarding

their favorite national team, or their favorite soccer league, or

talking about their girlfriend. This kind of stuff really does express

the community. We have a lot more [to show] than these huge … murals. We

were already painting on walls … way before we started to

professionally paint.”

Many of the quotes and poems that Mitwally refers to can be found in Amman’s 7Hills Skatepark,

tucked away at the foot of Jabal Luweibdeh, near the city’s old

downtown. They’re on what’s called an “open wall”—a wall or a space that

anyone can tag or paint, without permission.

Across the street from the skate park, a

local photographer has rented a studio that he hopes to turn into a

gallery. For now, a collage of brushes and dried paint clutters the

floor inside, next to makeshift ashtrays, newly finished paintings,

take-out shawarma, colored pencils, an anatomical skeleton named Haiker

(Arabic for “skeleton”), and Al Nayyar, who comes here to practice and

work as part of what she calls a “residency.”

“We don’t have a standard here, we don’t

have a scene,” she says of Amman. “It’s barely started. My goal is to …

create a standard in the public through street art.” But to achieve

that, Al Nayyar is adamant that she must improve. “I feel responsible

for the community … and it drives me toward that path.”

Art, she says, has literally saved her

life, pulling her back from the brink when she felt like ending it. “Art

was the only way to turn that destructiveness into constructiveness

through creation,” she says. “And when you see that creation on a

certain medium, like canvas, you start to analyze it and know more about

yourself. It was very therapeutic, and that impact really helped me.

[Now] I want to make it public.”

Working in the glow of a

small three-legged lamp, Al Nayyar sketches facial expressions in a

black-and-white journal, practicing the fundamentals, she says, while

humming a poignant but hopeful tune. Outside—as workers make the evening

commute home and kids leave the skate park wearing beanies and

jackets—street lights illuminate graffiti and murals in the distance.

© 2020 Atlas Obscura. All rights reserved.