La théorie quantique des champs

(traduction automatique)

L'explication la plus simple de la plus belle théorie quantique de la réalité

"J'avais entrepris de réfuter la théorie quantique des champs - et c'est le contraire qui s'est produit ! J'étais choqué."

— David Gross, physicien théoricien et lauréat du prix Nobel

Quand nous étions à l'école, on nous a appris que chaque matière est composée de minuscules petites particules appelées atomes ayant une masse centrale concentrée appelée noyau. Le noyau contient des protons chargés positivement et des neutrons sans charge. Il y a aussi des électrons qui tournent autour du noyau. Si vous êtes un étudiant universitaire, cette même chose est enseignée d'une manière légèrement différente et un peu plus avancée, que les protons et les neutrons ne sont pas des particules élémentaires car ils sont en outre constitués de quarks. Cela signifie que l'univers est composé d'une combinaison d'électrons et de quarks. Mais est-ce complètement vrai ?

Essayons de comprendre cela. L'univers n'est pas seulement composé d'électrons et de quarks, car dans ce modèle, nous ne pouvons pas savoir comment fonctionnent les différentes forces et de quoi sont faits ces quarks, électrons, etc. Nous préférons souvent parler de théorie des cordes, de mécanique quantique et de sujets tels que le multivers parce que nous avons entendu parler de ces termes à un moment donné quelque part et nous trouvons ces sujets très fascinants. Mais il existe aussi une telle théorie que la plupart d'entre nous ne connaissent pas, ou du moins ne comprennent pas. Cette théorie est la théorie quantique des champs.

Afin de comprendre l'univers, la théorie quantique des champs est l'une des meilleures théories car la plupart des prédictions faites par QFT se sont avérées vraies et il fonctionne mieux pour décrire la plupart des phénomènes physiques et le comportement de l'univers à un grand Le degré. Classiquement, QFT est souvent considéré comme un concept compliqué. Dans cet article, je vais essayer d'expliquer les bases de la théorie quantique des champs d'une manière aussi simple et compréhensible que possible.

Avant de commencer à en savoir plus sur QFT, essayons de comprendre ce que le modèle standard de la physique des particulesest. Il fut un temps où les scientifiques croyaient que les atomes étaient les plus petites particules de matière et qu'ils ne pouvaient plus être divisés. Ensuite, nous avons compris que les atomes ne sont pas vraiment les plus petites particules et qu'ils sont constitués de particules subatomiques - protons, neutrons et électrons. Lorsque la théorie quantique est entrée en jeu au milieu des années 1930 et 1940, elle a prédit l'existence de nouvelles particules, avec lesquelles nous n'étions pas familiers jusqu'à présent. Afin de comprendre ces particules nouvellement prédites, nous avions besoin de nouvelles théories. Lorsque ces nouvelles théories ont été formulées, elles ont prédit l'existence de quelques particules plus élémentaires. Plus tard, lorsque nous avons brisé les particules déjà existantes dans les accélérateurs de particules à haute énergie, nous avons découvert de nouvelles particules prédites. Avec les découvertes croissantes de nouvelles et nouvelles particules élémentaires,masse, spin, charge électrique, etc. Cela a donné naissance à un modèle pouvant tenir dans toutes les particules fondamentales réparties selon leurs propriétés intrinsèques. Le modèle a non seulement organisé ces particules, mais a également fourni un moyen d'expliquer les forces fondamentales de la nature en ce qui concerne leurs porteurs de force correspondants. Ce modèle est connu sous le nom de modèle standard de la physique des particules.

Comprenons ce que sont ces particules dans ce modèle et quels sont leurs rôles dans l'univers. Toutes les particules présentes dans l'univers se répartissent principalement en deux catégories : les bosons et les fermions. Les fermions sont responsables de la construction de la matière, que ce soit une table, un arbre, un livre ou un animal. Alors que les bosons sont les porteurs de force. La famille Fermionic est divisée en Quarks et Leptons. Il existe au total six types de quarks différents : Up, Down, Charm, Strange, Top et Bottom. Ils forment des protons et des neutrons à l'intérieur du noyau d'un atome. Les quarks ne sont pas des particules stables, ils se combinent donc en un groupe pour former des hadrons. Les hadrons sont ensuite divisés en mésons et baryons. Les particules baryoniques (protons et neutrons) sont formées par la combinaison de trois quarks. Les protons sont constitués de deux quarks Up et d'un down alors que les neutrons sont constitués de deux quarks down et d'un up. Les quatre types de quarks restants se combinent pour nous donner d'autres nouvelles particules. Les leptons, d'autre part, sont ces particules qui ne sont pas formées par des quarks, comme le muon, les électrons, le tau, le neutrino , etc. Ce sont des particules stables et, par conséquent, elles n'ont pas à se combiner les unes avec les autres pour former d'autres particules et ils peuvent exister indépendamment.

Le principe d'incertitude de Heisenbergprédit l'existence de ces particules qui existent sans aucune cause, et leur existence est probabiliste. Ces particules sont appelées particules virtuelles. De telles particules virtuelles sont trouvées expérimentalement. Indépendamment de la bizarrerie de ces particules, elles ont toujours tendance à suivre un certain schéma spécifique. Ces particules viennent toujours par paires. Ces paires contiennent deux types de particules dont l'une est une particule de matière régulière et l'autre est une particule d'anti-matière. Les particules d'antimatière sont les particules qui ont la même masse que les particules de matière mais qui ont des charges opposées. Lorsqu'un électron se forme, il se forme également une particule d'antimatière à côté de laquelle on appelle un positon, ou un électron positif. Lorsque ces particules matière-antimatière entrent en collision, elles s'annihilent pour produire de l'énergie pure. Comme les électrons, tous les autres leptons ont aussi leur paire d'antimatière. Les bosons sont de quatre types : les photons, les bosons W/Z, les gluons et les gravitons. Jusqu'au début du 19e siècle, les scientifiques croyaient que l'électricité et le magnétisme étaient deux forces différentes. Nous savons maintenant que ces deux forces ne sont que des formes différentes de la même force appelée force électromagnétique. L'électricité, la lumière visible, etc. sont les résultats de la force électromagnétique. Cette force est portée par les photons. Nous faisons l'expérience de ce type de force chaque jour dans nos vies, l'une ou l'autre forme. La force nucléaire faible est la deuxième force la plus faible de toutes qui est responsable de la désintégration bêta. Les bosons W/Z sont responsables du transport de cette force. La force nucléaire forte est la force la plus puissante de toutes qui est responsable de la liaison des nucléons (protons et neutrons) ensemble dans le noyau d'un atome. Les gluons sont les particules chargées de transporter une force nucléaire forte. La force gravitationnelle est la plus faible de toutes les forces fondamentales qui sont hypothétiquement portées par les gravitons. Malheureusement, nous n'avons pas découvert l'existence de telles particules, mais leur existence a été prédite par de nombreuses théories importantes. Jusqu'à présent, nous avons appris sur les particules de matière et la force transporte dans le modèle standard. Il existe cependant un autre type de particule dans la liste appelée boson de Higgs, qui est principalement responsable de fournir de la masse à l'autre particule. Je partagerai l'histoire du boson de Higgs dans un autre numéro. nous n'avons pas découvert l'existence de telles particules, mais leur existence a été prédite par de nombreuses théories importantes. Jusqu'à présent, nous avons appris sur les particules de matière et la force transporte dans le modèle standard. Il existe cependant un autre type de particule dans la liste appelée boson de Higgs, qui est principalement responsable de fournir de la masse à l'autre particule. Je partagerai l'histoire du boson de Higgs dans un autre numéro. nous n'avons pas découvert l'existence de telles particules, mais leur existence a été prédite par de nombreuses théories importantes. Jusqu'à présent, nous avons appris sur les particules de matière et la force transporte dans le modèle standard. Il existe cependant un autre type de particule dans la liste appelée boson de Higgs, qui est principalement responsable de fournir de la masse à l'autre particule. Je partagerai l'histoire du boson de Higgs dans un autre numéro.

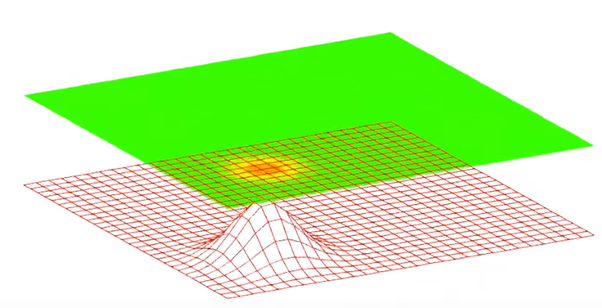

Les particules porteuses de force, les bosons, ont été prédites par la théorie quantique des champs. Comme son nom l'indique, la théorie quantique des champs est la combinaison de la mécanique quantique et de la théorie des champs. La mécanique classique est plus un jeu de déterminisme, ce qui signifie qu'avec les informations passées, nous pouvons en dire beaucoup sur l'avenir. La mécanique quantique, quant à elle, est une question de probabilités. L'acte de mesure, en mécanique quantique, altère la réalité des phénomènes physiques. La combinaison de tous les résultats possibles d'une particule est connue sous le nom de fonction d'onde qui peut être comprise comme les propriétés intrinsèques de la particule quantique comme la position, l'impulsion, la vitesse, etc. Un individu ordinaire observe le monde matérialiste mais un scientifique, en particulier, un physicien observe un monde avec de la matière et des champs. L'espace vide, en physique, n'est pas forcément vide. Essayons de le comprendre avec un exemple simple lorsque vous essayez de joindre les pôles similaires d'un aimant ensemble, vous ressentez une sorte de force répulsive. La région entre les aimants est considérée comme vide, mais nous ressentons toujours une sorte de force agissant là-dedans. L'espace considéré comme vide contient en fait un champ magnétique. De même, les espaces vides dans l'univers ne sont pas vraiment vides, ils contiennent des champs. C'est l'idée de base de la théorie des champs. les espaces vides dans l'univers ne sont pas vraiment vides, ils contiennent des champs. C'est l'idée de base de la théorie des champs. les espaces vides dans l'univers ne sont pas vraiment vides, ils contiennent des champs. C'est l'idée de base de la théorie des champs.

Maintenant, lorsque vous combinez la mécanique quantique et la théorie des champs, cela donne naissance à la théorie quantique des champs qui stipule que partout dans cet univers et à chaque instant du temps, il existe différents types de champs que nous ne pouvons pas voir comme un champ magnétique, un champ électrique , champ gravitationnel, etc. En fait, chaque particule élémentaire a son propre champ comme le champ de Higgs, le champ d'électrons, le champ de quarks, etc. Les physiciens représentent ces champs par des nombres. Nous voyons un ou plusieurs de ces nombres dans chaque point de l'espace. Les champs sont divisés en plusieurs types en fonction du nombre de numéros requis par un champ. Par exemple, le champ de Higgs est un champ scalaire car à chaque point de l'espace il nécessite un seul nombre pour décrire ce champ. Les champs électriques et magnétiques sont des champs vectoriels car ils nécessitent à la fois une amplitude et une direction pour leur description complète. Selon Sir Isaac Newton, le champ gravitationnel est un champ vectoriel alors que selon Einstein c'est un champ tenseur. Lorsque ces champs reçoivent de l'énergie, ils passent à des états d'énergie plus élevés formant une sorte de ridée comme dans l'eau. Ces ondulations ainsi formées sont appelées particules. Par exemple, lorsque des ondulations se forment dans le champ d'électrons, des électrons se forment. De même, les ondulations dans les champs de quarks nous donnent des quarks. Lorsque ces ondulations deviennent silencieuses, les particules correspondantes disparaissent également. Au point où nous donnons l'énergie dans ces champs, la particule se forme à ce point et lorsque cette énergie commence à se répandre à travers le champ, nous disons que la particule se déplace. Pour certains champs, nous devons fournir une grande quantité d'énergie pour produire les particules. Certains champs nécessitent moins d'énergie pour générer la particule. Le principal facteur qui détermine la quantité d'énergie nécessaire à un champ pour produire une particule dépend de la masse de la particule correspondante associée au champ.

Par exemple, les bosons de Higgs sont beaucoup plus lourds que les électrons. Par conséquent, le champ de Higgs nécessite une énorme quantité d'énergie pour générer ces particules. Nous ne pouvons le faire que dans des accélérateurs de particules comme le Large Hadron Collider. Jusqu'à présent, nous avons compris la génération de différentes particules en termes de champs. Voyons maintenant comment fonctionnent les forces fondamentales selon la théorie quantique des champs.

Les champs existent au même endroit dans l'espace et le temps en raison desquels nous voyons souvent l'échange d'énergie entre et parmi les différents champs. C'est ainsi que les forces fonctionnent et, à cause de ce phénomène, une particule est parfois convertie en une autre. C'est l'une des meilleures théories pour comprendre la nature et la réalité au niveau quantique jusqu'à présent. Il y a encore beaucoup de questions associées à la théorie quantique des champs. Il n'a pas été en mesure d'expliquer l'existence de la matière noire et de l'énergie noire. De nombreux physiciens pensent que la matière noire est également le résultat de l'énergie dans certains domaines que nous ne comprenons pas encore.

Sunny Labh

Merci beaucoup d'avoir lu. Si vous aimez mon travail et souhaitez me soutenir alors vous pouvez devenir membre médium en utilisant ce lien ou m'acheter un café ☕️ . Continuez à suivre pour plus d'histoires de ce genre.