Astrologers Were the Quants of the Ancient World

by Alexander Boxer

August 7, 2020

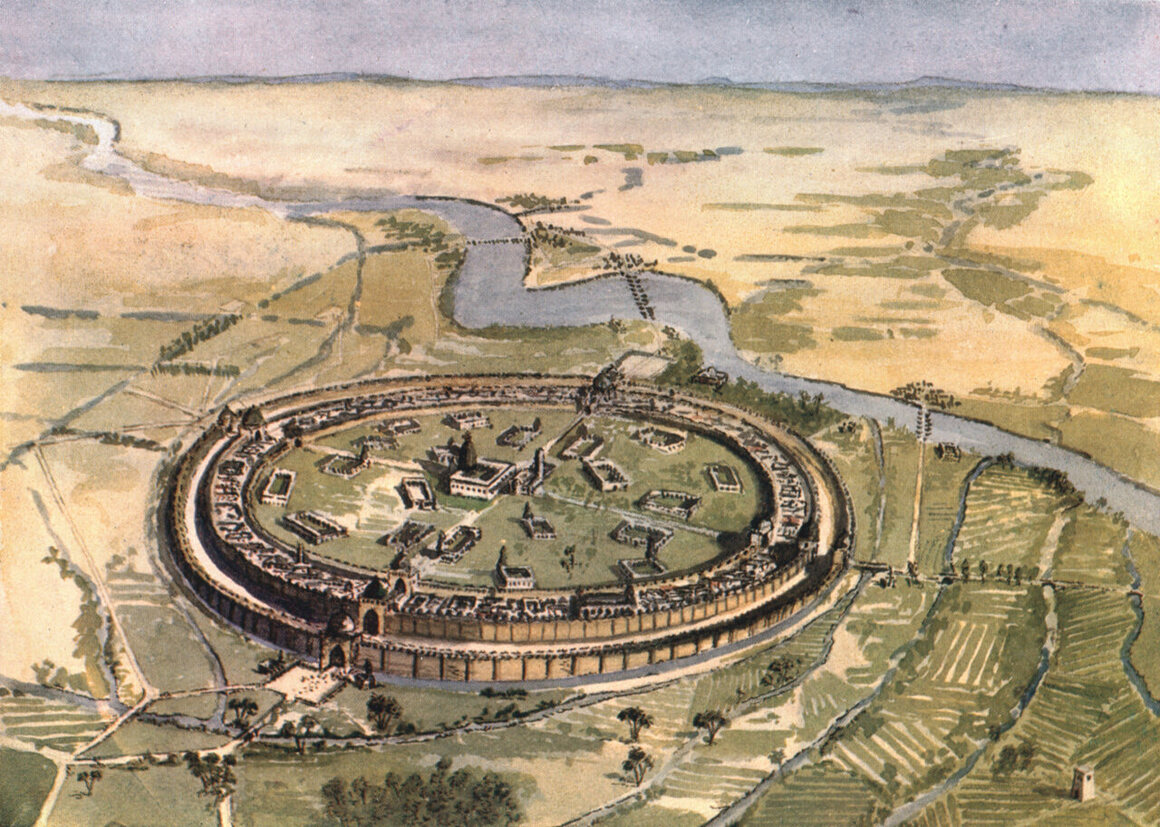

The location was perfect for a

new capital city. There were, of course, the standard prophecies that a

great metropolis was destined to arise there. Even more persuasive,

perhaps, were the reports that of all the districts along the Tigris

River, the site was said to be the least infested with mosquitoes. But

the main reason the caliph Abu Jafar al-Mansur chose to build his capital at Baghdad was that, with the absorption of Persia into Dar al-Islam, the “abode of Islam” had spread far to the east, and the place that would be Baghdad lay right at its heart.

But what good is the right place if it’s not also the right time? Accordingly, al-Mansur summoned his top astrologers—Nawbakht, a Persian, and Masha’allah, a Jew—to determine the optimal moment to inaugurate construction. Remarkably, the horoscope of Baghdad’s foundation has been preserved in the writings of al-Biruni, one of the foremost astronomers of a few centuries later. Baghdad’s

founding can therefore be dated with especially high confidence to the

afternoon of July 30 in the year 762. At that precise instant, Jupiter,

the planet of kingdoms and dynasties, was rising in the east, while

Mars, the planet of war, was setting in the west. Indeed, no horoscope

could have been more appropriate for a city that al-Mansur insisted be called Madinat as-Salam, the “City of Peace.”

Looking back at Baghdad’s founding, there is a strong case to be made that al-Mansur’s personal obsession with astrology was the not-so-secret impetus for his city’s

scientific pursuits. Certainly, the almost manic translation of Greek

texts into Arabic that took place in the city appears a lot less

eccentric if it’s understood as part of a government initiative to harness the power of the stars. Prior to seizing the caliphate, al-Mansur

had cultivated his power base among the conquered provinces of Persia.

There, in return, he was influenced by a Persian tradition that saw the

fall of Persia and the rise of the Arabs in explicitly astrological

terms. One of the earliest expositors of this idea was none other than

Masha’allah, the Jewish astrologer hand-picked

by the caliph to cast the horoscope for his new capital city. Just as

the planets rose and set in their allotted times, so, too, it was said,

did kingdoms, dynasties, and even religions. The most importance of

these cycles, insofar as they were supposed to herald events of global

significance, were the successive conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn.

Astrology’s insistence on linking earthly events

with celestial causes in this way may seem, today, like an easily

dismissed irrationality. Yet the astrologers of antiquity were no

mushy-headed mystics. On the contrary, astrology was the ancient world’s

most ambitious applied mathematics problem, a grand data-analysis

enterprise sustained for centuries by some of history’s most brilliant

minds, from Ptolemy to al-Kindi to Kepler. Astrology’s demand for

high-precision planetary data led directly to Copernicus’s revolution

and, from there, to modern science. Astrology’s challenge—teasing out

inferences from numerical data, determining which patterns are real and

which aren’t—remains fundamental in science today, too, especially as

society relies increasingly on complex, data-driven algorithms.

Astrologers were the quants and data scientists of their day; those who

are enthusiastic about the promise of data for unlocking the secrets of

our world should note that others have come this way before. Our

irrepressibly human penchant for pattern-matching makes the history of

astrology—a history that can bring together astronomy, statistics,

cryptology, Shakespeare, COVID-19, presidential assassinations, and even

the New York Yankees in a dance of coincidence and

correlation—surprisingly timely and always fascinating.

Saturn, the outermost planet visible to

the naked eye, takes about 30 years to complete an orbit through the

zodiac constellations of the night sky. Jupiter, the largest and the

next-most-distant planet, takes about 12 years. As these two astral

giants chase each other around, Jupiter catches up to and passes Saturn

roughly once every 20 years. The moment when these planets, or any two

heavenly bodies, line up in ecliptic longitude is called a conjunction.

As a curious consequence of orbital mechanics, every conjunction of

Jupiter and Saturn occurs almost exactly one third of the way around the

zodiac from the spot of the previous conjunction. Thus, three

successive Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions will trace an almost-perfect

equilateral triangle in the sky.

To give an example: If

Jupiter and Saturn come into conjunction in the zodiac sign of Aries,

then approximately 20 years later, their next conjunction can be

expected to occur in Sagittarius. The following conjunction, 20 years

after that, will be in Leo, before it cycles back to Aries. Aries,

Sagittarius, and Leo are the three zodiac signs associated with the

element of fire. Thus, in this example, the sequence of Jupiter-Saturn

conjunctions occurred entirely within the triangle of fire signs, a

pattern also known as the fiery trigon or triplicity.

Of course, the astral triangles traced out this way don’t

exactly overlap, and so after about 10 conjunctions, or roughly 200

years, the entire pattern migrates to the next triplicity of signs. Over

about 800 years, the sequence of Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions will

slowly cycle through all four triplicities: fiery, earthy (Taurus,

Capricorn, Virgo), airy (Gemini, Aquarius, Libra), and watery (Cancer,

Pisces, Scorpio).

Masha’allah

and his successors saw in this sequence an organizing principle for the

entire history of the world. Local political changes, they suggested,

were augured by the regular or “little

conjunctions” that occur roughly once every 20 years. Larger shifts of

kingdoms and dynasties, about every 200 years, were heralded by “middle

conjunctions,” when the sequence migrates from one triplicity to

another. Finally, the most momentous historical upheavals, such as the

fall of empires or the rise of new religions, were portended by “great

conjunctions,” once in a millennium, when the sequence of conjunctions

has completed a full cycle through all four zodiac triplicities: fire,

earth, air, and water.

The chronology Masha’allah

developed with this theory placed the creation of the universe in the

year 8292 B.C., with the first conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn

assigned to the year 5783 B.C., in the sign of Taurus. Masha’allah

then hopped through the history of the world, conjunction by

conjunction, pausing only to comment on a select few that he deemed to

be especially history-altering.

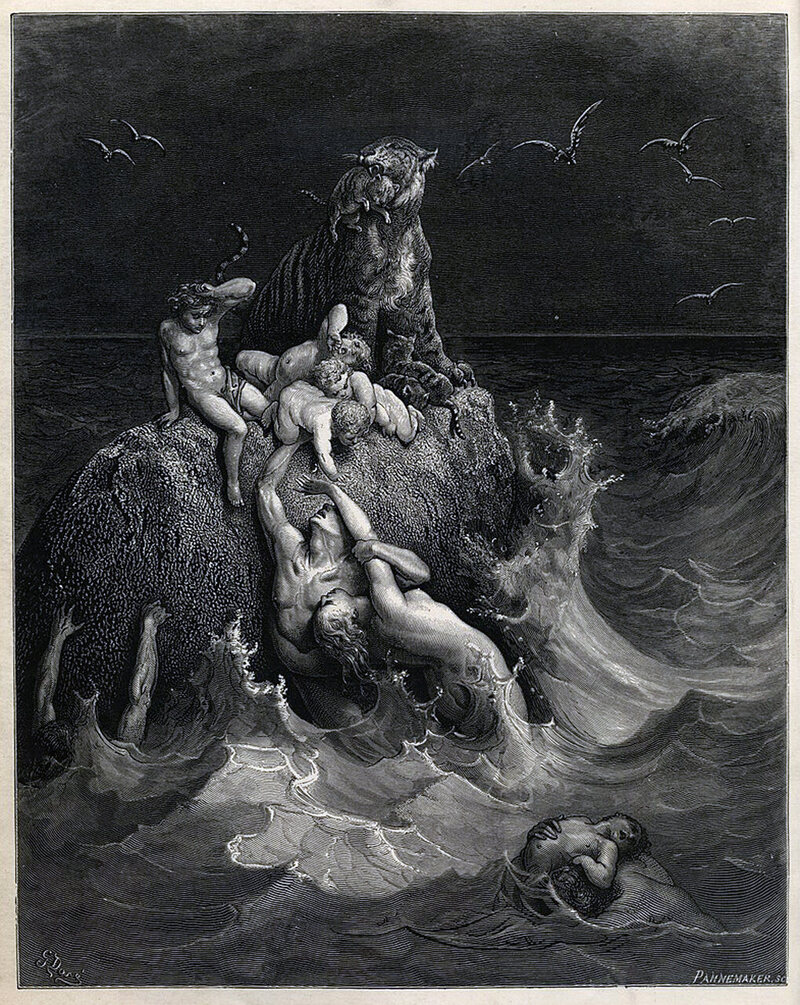

There’s

the Great Flood, which he dated to 3361 B.C., naturally during a watery

triplicity. After leaping past several cycles of great conjunctions, he

arrived at 26 B.C., the time of a shift from a watery to a fiery

triplicity. According to Masha’allah,

this transfer heralded the birth of Christ and the advent of the

Christian era. It also adds an interesting spin to John the Baptist’s prophecy that, although he baptized with water, the one who followed him would baptize with fire.

Skipping ahead a half-millennium, Masha’allah

next examined the conjunction of the year 571, which brought the

sequence back to another watery triplicity. This transfer presaged the

birth of Muhammad and the rise of the Arabs, whose sign, according to

Masha’allah, was Scorpio.

Finally arriving at the events of his own day, Masha’allah regarded the conjunction of 769—the end of a watery triplicity and the beginning of a fiery one—as an indicator of an ebb in Arab power and a resurgence of Persia. As for Masha’allah himself, it’s

believed that he died around the year 815. He did, however, extend his

chronology to predict, entirely accurately although rather

unimaginatively, continued political strife between Arabs and Persians.

Recreating Masha’allah’s

chronology of Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions using modern data reveals

that his approximations for the orbital periods of Jupiter and Saturn

were actually pretty decent, even if there’s never really a sharp

transition between one triplicity and the next. The pattern of small,

middle, and great conjunctions still stands out in modern data, a

charmingly captivating system. It’s easy to see why anyone with a knack

for historical dates might get engrossed in its narrative possibilities.

Were the renewed conquests of Islam under the Ottomans due to the

return of a watery triplicity? Is the Middle East more susceptible to

European invasion, by crusaders or colonialists, when an earthy

triplicity holds sway? It hardly seems any more arbitrary than, say, the

ancient, medieval, and Renaissance periods taught in school.

In fact, astrologically organized histories were considered quite scientific during the Medieval Period—or,

if you prefer, during the seventh great conjunction cycle between the

fiery triplicities of 769 and 1603. The most prominent popularizer of

this approach was Abu Mashar, the preeminent astrologer of Baghdad the

generation after Masha’allah. And among its notable proponents was Abraham ibn Ezra, medieval Spain’s famed Jewish poet and philosopher, who inserted the theory into his commentary on Exodus.

Christian chronologists were similarly

swept up. The dreaded return of the fiery triplicity in 1603, a year

that saw the death of England’s

Queen Elizabeth I, was examined at length by no less an authority than

astronomer Johannes Kepler. Several writers even went so far as to rely

on the scheme for some pretty bold predictions. German monk Johannes

Trithemius, for example, writing around the year 1500, bluntly asserted

that liberty would not be restored to the Jews prior to August 1880. In

fact, this is more or less exactly when the first wave of Zionist

settlers immigrated to Ottoman Palestine. The medical faculty of Paris

blamed the Black Plague, which arrived in Europe in 1347, on a

corruption of the atmosphere caused by the conjunction of Jupiter,

Saturn, and Mars in Aquarius the year 1345. (Incidentally, this is the

exact same configuration that has prevailed during the COVID-19 pandemic

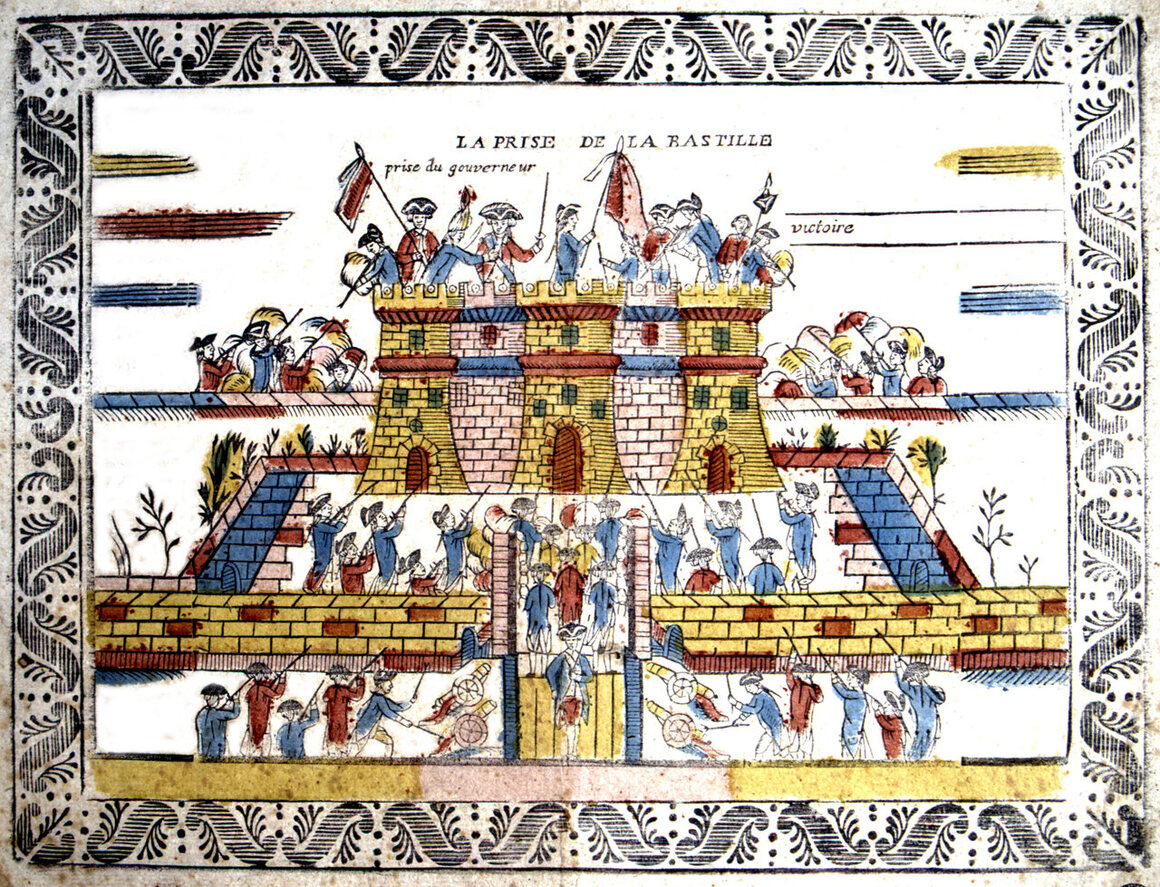

of 2020.) But most notoriously of all, French Catholic cardinal Pierre d’Ailly,

writing around 1400, concluded his astrological history of the world

with a warning that the Antichrist could be expected to arrive in the

year 1789. Depending on how reactionary your views are regarding the

French Revolution, this may strike you as humorously prescient.

Unlike with other astrological

assertions, where an analysis might entail an elaborate hunt for the

faintest hint of a correlation, the correlations in the conjunction

theory of history seem to leap out from everywhere. It is roughly

analogous to the engineering distinction between noise, in which nothing

looks like a signal, and clutter, in which everything looks like a

signal. Perhaps, though, an even better analogy can be made to

cryptology: History, here, is like a secret code, with astrology as its

key.

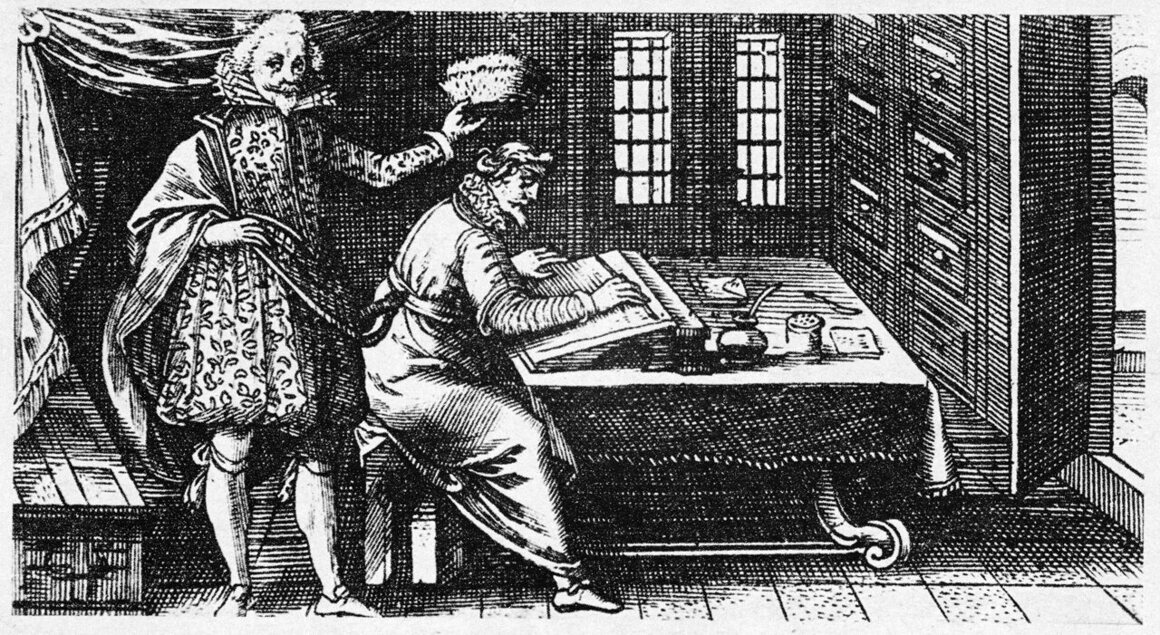

The art of concealing a message

in secret writing is called cryptography and its practice is as old as

writing itself, but deciphering a secret message without a key requires

cryptanalysis—which emerged as a science only in Baghdad under the

Abbasids. The father of cryptanalysis was Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, a man who was deeply devout, deeply mathematical, and deeply obsessed with astrology. His treatise On Rays, for example, has to be history’s most valiant attempt to give astrology—and magic—a firm, philosophical foundation.

As al-Kindi

recognized, the art of writing is itself an act of magic, in its power

is to transmit thoughts and emotions across vast distances with symbols

alone. Given al-Kindi’s sensitivity to the power of symbols, it’s altogether apt that he, together with his famous contemporary al-Khwarizmi,

was instrumental in promoting the adoption of Hindu numerals. The magic

of this system derives from the digit 0, which permits, through its use

as a placeholder, every natural number to be expressed with just 10

abstract characters.

The Arabic word for the digit 0 is صفر, sifr. When this system was introduced to Europe by Fibonacci (of the famous sequence), sifr was Latinized as zephirum, which gave rise both to the word “zero” and the word “cipher.”

To medieval Europeans, who were used to seeing a quantity such as

one-thousand, two-hundred and two written as MCCII, the characters 1202

doubtless did look like a secret code, or cipher.

Living in Baghdad, where transcription,

translation, and interpretation rose to the level of a spiritual calling

as well as an intellectual one, al-Kindi would have been well aware of

the power of symbols to conceal. But al-Kindi outstripped all of his

predecessors in compelling symbols to reveal their secrets. His

“Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages” was the first to show

that simple ciphers can be cracked by a technique known today as

frequency analysis.

And yet, not all of the universe’s

secrets are encrypted with a cipher. Occasionally, some of the deepest

secrets can be found hiding right before our eyes. The practice of

concealing a message in plain sight, so to speak, is called

steganography, from the Greek stego (στέγω), meaning “cover,” and grapho (γράφω), meaning “write.” Steganography is a much more devious craft than conventional cryptography since, while it’s

obvious that a text in cipher is concealing a secret message, however

difficult it may be to decipher, the object of steganography is to

deflect suspicion that there’s any secret at all.

Simply put, anything can, and most

everything has, historically, been used to cloak secrets in settings

that are otherwise perfectly public, be it poetry, music, botanical

drawings—or star charts. In fact, as recently as 1996, a hidden message

was discovered to have been concealed in the astrological tables of a

notorious occult manuscript from the 1500s. The mischievous monk who

devised this scheme was Johannes Trithemius, the same one who predicted

the political fortunes of the Jews. Remarkably, he even went so far as

to write an entire book about steganography which, appropriately enough,

he disguised to look like a book of spells for summoning spirits. (A

pretty neat trick, don’t you think?)

The ability to look at the world and see what others cannot is generally taken as a mark of genius. But for every al-Kindi, Copernicus, or Einstein, there have been thousands who insist on seeing connections that simply aren’t

there. Astrology likes to hover on the boundary between the two,

presenting endless layers of planetary patterns, from perfectly real to

positively paranoid.

Returning to Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions,

why were they so often interpreted as a code to the secrets of history?

With a traditional cipher, the correct key results in a perfectly

readable message, while the wrong key returns gibberish. With

steganography, however, nothing can be ruled out. Anyone who maintains

that there’s no correlation between

the conjunctions of the planets and the events of world history is in

the unenviable stance of having to prove a negative. The mathematical

procedures pioneered by al-Kindi, the

original father of cryptology, are powerless here. We can, however, turn

to the man who is rightly called the father of modern cryptology:

William Friedman, best known for breaking the Japanese diplomatic

ciphers in the run-up to World War II.

Oddly, William Friedman, America’s

preeminent 20th-century codebreaker, began his cryptologic career when

he was hired, with no prior experience, to search for hidden messages in

the works of William Shakespeare. Specifically, he was asked to verify

the existence of certain ciphers, to use the term loosely, supposedly

proving that the works of Shakespeare were actually authored by Francis

Bacon, the essayist, philosopher of science, and onetime chancellor of

England. Proponents of these ciphers claimed that individual letters in

the early printings of Shakespeare’s

plays were marked in subtle ways. With a generous eye and a suggestive

mind, true believers had managed to combine these letters into

startlingly elaborate confessions that Shakespeare had been a mere front

for the genius of Bacon. Friedman thought all of this was lunacy.

Later, during his retirement, Friedman

was determined to settle the matter once and for all. In this, he was

joined by his wife, Elizebeth, whom he had first met as a fellow skeptic

in the original Shakespeare cipher group. Like William, Elizebeth would

become a distinguished cryptologist in her own right, leading, for

example, the U.S. Treasury Department’s efforts to decipher the codes of bootleggers and rum-runners during Prohibition.

Operating according to the principles of unbiased scientific inquiry, the husband-and-wife cryptology team published The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined in 1957, which demonstrated, one by one, that none of these so-called ciphers could stand up to scrutiny. Their work is directly relevant to astrology because they address head-on the question of how to determine if a signal, or pattern, or secret code is real. (Or if you’re just nuts.)

Generally speaking, there’s

no mathematical formula or algorithm that can solve a steganographic

cipher. The Friedmans did, however, stipulate two general conditions

that any such solution must satisfy. First, whatever decryption

procedure is proposed must give a sensible result when applied

rigorously. The main problem with the so-called Baconian ciphers was that their “discoverers”

were constantly inserting letters here or skipping letters there to

make their systems work. Such arbitrariness should be taken as an

argument against these ciphers having been used in the first place. The

conjunction theory of history exhibits a similarly ample amount of

wiggle room, since the conjunctions themselves don’t need to coincide with any historical date exactly. Instead, it’s

enough for a conjunction merely to foreshadow, in some vague way, an

upcoming event or era. Thus the fiery triplicity said to presage the

birth of Jesus is permitted to begin a full quarter-century earlier. And plenty of other conjunctions, unattached to world events, are simply left out.

Yet, to give a counterexample, if I told

you that the first letters of the nine preceding paragraphs, including

this one, spells out ASTROLOGY (“And,”

Simply,” … “Yet”), there should be no doubt that this message was

placed there on purpose. The method is applied rigorously, and the

probability of these nine letters occurring this way by chance is

impossibly small.

The second general

condition stipulated by the Friedmans is that the solution must be

unique. As they demonstrated colorfully in their book, a decryption

method that tells you that Bacon was the true author of Shakespeare’s

plays can hardly be valid if the same method can be used to reveal that

Theodore Roosevelt, Gertrude Stein, and even William Friedman himself

were in on the plot. The significance of any one solution is diminished

in accordance with how easy it is to produce competing, if not

contradictory, solutions. As the Friedmans put it, “Just

as there is only one valid solution to a scientific or mathematical

problem, so there is only one valid solution to a cryptogram … to find

two quite different but equally valid solutions would be an absurdity.”

Thus, whatever we conclude about the

conjunction theory of history should, properly, depend upon how uniquely

we think it correlates with one sequence of historical dates and not

any others. This, in turn, suggests a pattern-matching

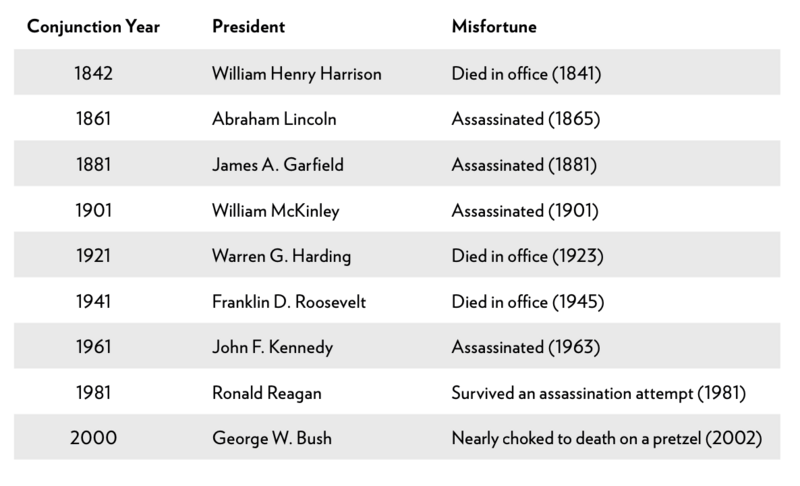

game. For instance, looking back at just the last 200 years, we can

observe a remarkably strong correlation between the nine most recent

Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions and the terms of U.S. presidents who either

died in office, were assassinated, or survived near-death mishaps.

We could also, if we wish, note an intriguing connection between the conjunctions and the development of space exploration: 1901—Orville and Wilbur Wright experiment with powered flight; 1921—Robert Goddard experiments with liquid-fuel rocketry; 1941—Wernher von Braun begins development of the V-2 rocket; 1961—Yuri Gagarin is the first man in space; 1981—the maiden launch of Columbia, the first space shuttle; 2000—the initial manned mission arrives at the International Space Station.

And yet, maybe the true,

cosmic significance of a Jupiter-Saturn conjunction is to ensure that

the New York Yankees make it to the World Series, as, indeed, they have

in every conjunction year since the game has been played: 1921, 1941,

1961, 1981, and 2000. (The first modern World Series was played in

1903.)

So, how many patterns can

you pick out? Whatever you predict, get ready to have it tested. The

next Jupiter-Saturn conjunction is coming: December 21, 2020, the exact

date of the winter solstice.