(In)visible Translations: An Interview with Douglas Robinson

George Salis: Can you give us an overview (as descriptive as you’d like) of Finnish writer Volter Kilpi’s oeuvre?

Douglas Robinson: It’s strange. It comes in three disparate bursts: first, around the turn of the century, three neo-romantic novels focused on biblical and mythological characters and themes, along with a collection of ecstatic essays; then, after 15 years of silence, two impassioned political tracts in the years of Finnish independence from Russia (1917, 1918); then, after another 15 years of silence, the major modernist works of the 1930s: the Archipelago series, consisting of his magnum opus Alastalon salissa (“In the Alastalo Parlor,” 1933), his follow-up short story collection Pitäjän pienemmät (“The County’s Littler Guys,” 1934, partly consisting of bits and pieces that he cut from Alastalo), and the novel Kirkolle (“To the Church Village,” 1937); then the last two works, Suljetuilla porteilla (“At Closed Gates,” 1938) and Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle (Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia), left unfinished at his death and published posthumously in 1944. Critics have tried to construct continuities—the meandering voices of the early novels as anticipating Alastalo, the right-wing zealotry of the political tracts projected onto Alastalo, etc.—but really there is no way to predict the explosion of brilliant modernist experimentation in the works of the 1930s.

GS: Is Kilpi’s masterpiece Alastalon salissa truly comparable to Ulysses?

DR: In some ways, but to my mind rather peripheral ones. A brilliant Finnish poet, critic, and theorist named Leevi Lehto (1951-2019), who published an incredible Finnish translation of Ulysses in 2012, has made the case, and I talked to him about it before his death; but much as I admire his brilliance, his juxtaposition of the two always seemed circumstantial to me. Back in the late 1940s the avant-garde writer and composer Elmer Diktonius (1896-1961)—whom Kilpi tried to hire to translate his work (Diktonius gave up: too difficult)—made a rather different case for the parallels between the two novels. There are stream-of-consciousness chapters and sections in the novel, but they consist of more coherent discursive thinking than anything in Joyce, and they are often blended with Jamesian close third-person narrations and even some premodern omniscient third-person narrations. I would say, in general, that Alastalo is much closer to Proust than to Joyce. In fact, Alastalo was based on Kilpi’s ancestors: both of his grandfathers and his father play starring roles in the novel; Alastalo was his paternal grandfather’s real-life house, where his father was born (and the house still stands today, with the same name), and so on. If Proust’s Recherche is stylized modernist autobiography, Kilpi’s Alastalo is what we might call stylized modernist prenatal autobiography.

GS: In Books from Finland one would-be translator explains, “Reluctantly (I really have tried) I have been driven to conclude that Alastalon salissa is untranslatable, except perhaps by a fanatical Volter Kilpi enthusiast who is prepared to devote a lifetime to it.” Have you considered translating it or do you also think it’s untranslatable?

DR: I think what David Barrett meant by “untranslatable” is “very difficult (for me) to translate.” The novel was published in Thomas Warburton’s 1997 Swedish translation, and Stefan Moser’s German translation is due to be published in the next few months: not at all untranslatable! I have been translating bits and pieces of Kilpi’s novel for a monograph I’m writing titled “Translating the Monster: Volter Kilpi in Orbit Beyond (Un)translatability,” which will also feature this Gulliver book. I’ve translated the entire first chapter of Alastalo, and will print that in an appendix to the monograph. I find translating Kilpi daunting but heady. He reinvents the Finnish language, which makes translating incredibly difficult—but also (as I see things) gives me license to reinvent the English language. (I am certainly a Kilpi enthusiast, and I suppose I don’t take “fanatical” to be an insult; but I won’t be devoting my entire life to it. 2-3 years in retirement, probably.)

GS: What made you decide to translate the unfinished manuscript Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia (Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle)? Before he died of a stroke, Kilpi told his son about how he had planned to finish the manuscript, but what gave you the artistic audacity to attempt to finish the unfinished Finnish (in Swiftian English, no less)? Is the original Finnish written with a Swiftian flair too?

DR: I’m not sure I would call Kilpi’s Finnish in any obvious way Swiftian. His Finnish is weird, the way all of his writing of the 1930s is weird, and it’s archaic, so arguably Swiftian, but not recognizably so. My original idea to translate that unfinished novel was born out of Kilpi’s playful claim to have found Lemuel Gulliver’s original English manuscript and translated it into Finnish. The “found translation” meme! Rabelais used it in Gargantua and Pantagruel back in the 1530s; Cervantes used it in Don Quixote; it’s one of my favorites. And I thought: okay, so what if I were to pretend, equally playfully, to have found the same English manuscript and edited it for publication? Then I would need to translate Kilpi’s unfinished ms into Swiftian English (Gulliver would not have written the English of our day!) and write the novel to the end Kilpi told his son he was planning. The Pale Fire fun I had with the paratexts surrounding the original truncated Finnish novel just sort of emerged as I began to work on the project.

GS: Why do you think it took this long for any translation of Kilpi’s work to be published?

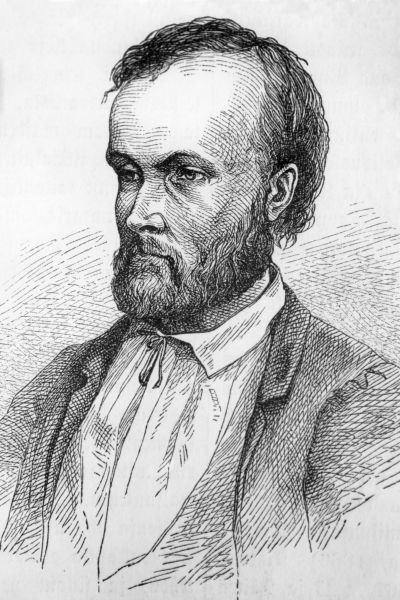

DR: Kilpi was forgotten for a half century after his death in 1939. He began to be rediscovered and read in the late 1980s—right around the time I moved out of Finland, so I missed it. In 1992 a poll launched by Finland’s major national daily voted his Alastalo the greatest Finnish novel ever—taking everyone by surprise. Everyone always expects Aleksis Kivi’s 1870 novel about seven brothers (Kilpi’s favorite novel, and one of my favorites as well) to win these polls. So really we’ve only had three decades to mull over his work. And it’s so difficult that no native speaker of Finnish feels entirely comfortable with it; his Finnish readers have observed that it feels like they’re reading a foreign language. That sets the bar very high for translators, obviously!

GS: You mentioned that you devoured Barth as a young man. What was that feast like back then and did The Sot-Weed Factor also animate you on some mental level as you wrote that archaic style? Perchance Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon?

DR: The Sot-Weed Factor and Mason & Dixon did both inspire me, yes—not just in the use of archaic English, but the rollickingly playful use of archaic English. The boisterous rhythms of those novels, and of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and of Sir Thomas Urquhart’s 1663 translation of Rabelais, kept exploding inside me as I worked. That’s partly what makes translating Alastalo such a heady experience as well: here is an incitement to cut loose! I should say, too, though, that I translated Aleksis Kivi’s 1870s novel Seitsemän veljestä—the novel that everyone expected to be voted, again, as Finland’s greatest, because it truly is great—as The Brothers Seven in the same way, with boisterous, rambunctious archaic English. Kilpi’s late modernist work isn’t nearly as laugh-out-loud funny as Kivi’s, and the style is way more intricately convoluted; but there is a boisterousness to both writers that tickles me deep down.

GS: The novel is subtitled ‘a transcreation.’ To your knowledge, has anything like this been done before?

DR: Transcreation is an established term, certainly. The Brazilian poet Haroldo de Campos, who compared translation to cannibalism, compared transcreation to a blood transfusion. But I don’t know of any other transcreation that has done precisely what I do here—the Pale Fire experiment.

GS: You mentioned Pale Fire. What are your thoughts on that novel and how has it influenced this transcreation?

DR: I love that novel. I don’t claim to understand all the tricks Nabokov pulls in it—the idea that Kinbote’s “transcreation” of John Shade’s poem was actually written from the afterlife by Shade’s daughter Hazel, say—but the complexity of the intertwined genres (poem, commentary, index) is deeply appealing to me. The idea that Kinbote is clinically insane, and takes possession of Shade’s poem in order to tell a romanticized adventure story about his supposed royal escape from Nova Zembla, and so on … the many layers of twisted retelling that make up that novel stir my imagination in far-reaching ways. Pale Fire works on my imagination at such a deep level, however, that I didn’t consciously decide to filter Kilpi’s Gulliver through it; it just sort of started happening, and it wasn’t until I’d finished that the Pale Fire connection occurred to me. I mention in the “editor’s introduction”—narrated by a Kinbote-like paranoid named Douglas Robinson—that I was once quite viciously accused of Kinbote-like theft by the Finnish editor-in-chief of the Aleksis Kivi Critical Edition project, just because in the review I was asked to write (about one volume in the series) I pointed out a series of errors he had made. I was taken aback by the sustained malice of his attack on me, but accusing me of being like Kinbote didn’t hurt at all: it was a kind of flattery! (I recreate that vicious attack, playfully, in the “reader’s report” I wrote and attributed to the fictitious Prof. Julius Nyrkki, whose surname means “fist”—I use his attack to highlight everything I’m proudest of in the transcreation. In the course of calling me a shameless liar, thief, and hoaxer, too, he tells the most truth about the project in the entire volume.)

GS: Whereas your addition to the manuscript is satirical, Kilpi’s portions are loosely satirical at best. Why do you think Kilpi chose to adopt a Swift character while avoiding the Swiftian style of satire?

DR: Probably he didn’t have a satirical bone in his body. He got the idea for the novel while reading Bertel Gripenberg’s Swedish translation of Poe’s “Descent into the Maelström.” The idea must have been to write a sailing tale (Kustavi, where he lived most of his life, was a shipbuilding community, and his father and both of his grandfathers were shipbuilders who captained the ships that they built) that veers into the holes-at-the-poles theory (which Poe too uses in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym) and SF time travel in order to bring characters from the past into his time, 1938. My guess is that it was only at that point, fairly late in the brainstorming process, that he thought of Gulliver—of having Gulliver and his shipmates set out in 1738 and be propelled exactly two centuries into the future. I’m not sure Swiftian satire ever entered into his imaginings! Though if it did, it might have been the relatively superficial kind of satire that attacks: shows how appalled eighteenth-century people would have been at the modernity of his day. I love satire, and love writing it, and used it to vent my spleen at the Trump “presidency,” but much more pressingly than satire I had epistemological play on my mind—and indeed the whole sequence in which Gulliver and his shipmates are projected into the King James Bible was much more interesting to me for that reason. I guess I’m still doing satire there—satirizing the Old Testament, by having Gulliver embody one of the most bizarre characters in the entire book, Captain of the Host of the LORD in Joshua 5:13-15, and using him as a witness to horrific mindless genocide—but playing with the illusion of reality, propelling a novel character into the Bible, a text-within-a-text, was more interesting.

GS: What made you choose a European publisher of textbooks? Rather than, say, Deep Vellum or Archipelago Books, for instance?

DR: I sent proposals to both of those presses, and two dozen others like it—and never got a single acknowledgement. I had a long conversation about it with Chad Post at Open Letter Books, and he encouraged me to send a proposal—and then never got even an acknowledgement from him either. I tried university presses. I must have sent queries or proposals to 40-50 presses, and received a total of three (negative) replies. It was quite discouraging! And Zeta Books is an edgy publisher of philosophical books, not (to my knowledge) textbooks. I have a good friend who is also from Romania, and she encouraged me to publish my book on Friedrich Schleiermacher’s 1813 Academy address on the different methods of translating with them: I wanted to publish the book in Berlin in the bicentennial year, 2013, and none of the Berlin publishers were responding (I would have loved to publish it on June 24, 2013, exactly two centuries after the address was delivered). I met my Romanian friend at a conference in Germany that summer, and after I had complained about the German publishers giving me the cold shoulder, she recommended Zeta Books. I asked around about them, heard nothing but great things, and decided to take a chance—and they were amazing. They published my book in one month, start to finish—and did it with meticulous professionalism. So when I was unable to find a publisher for my translation of Aleksis Kivi’s The Brothers Seven, I turned to them, and they published it brilliantly as well. With Kilpi, I was determined to find a more traditional small press in the Anglophone world, but failed—so I turned to Zeta Books a third time. It’s an odd venue for a book like this, certainly: why Romania? But the press is owned and run by philosophers with a nose for the quirky, and they have responded to my quirky books with great enthusiasm and intuitive understanding! And to my delighted surprise, there has been a lot of advance excitement about this Gulliver book out in the world as well.

GS: In 1980, you wrote a monograph about John Barth’s Giles Goat-Boy. Barth became a nonagenarian this year. Can you reflect on his work and talk about why you love it?

DR: I have enjoyed all of his novels and stories, but especially love The Sot-Weed Factor and Giles Goat-Boy. Back when I was working on Barth, I was obsessed with the nature of postmodernism, and tended to define it along lines marked out by those big books of Barth’s, and also Coover’s (The Public Burning) and Pynchon’s (especially Gravity’s Rainbow back then, but later also Mason & Dixon). I guess what I loved about that flavor of postmodernism was the idea that you could write metafiction, playing epistemological games with the illusion of reality, and have enormous fun doing it, and bringing the reader into your fun—and also write compelling stories. I hated the notion that metafiction meant mauling the joy of reading—that playing with the illusion of reality was a purely intellectual activity, to be admired but not enjoyed. I love reading fiction, and don’t want to be deprived of that pleasure! And the two extremes of domestic realism and, say, Robbe-Grillet’s nouveau roman both seem to suck the pleasure out of reading. Writers like Barth, Coover, Pynchon, Gass—and Kilpi, and Shishkin, etc.—get my blood pumping!

GS: What are some other Finnish masterpieces that you’d like to see in translation and what can you tell me about them?

DR: Possibly Neuromaani (a punning title that could be translated Neuronovel, Neuromaniac, or My Neurocountry), the big 2012 novel by Jaakko Yli-Juonikas, who has been called Finland’s greatest living writer. I’ve been hired to translate several contemporary novels, notably comic novels by writers like Arto Paasilinna and Mikko-Pekka Heikkinen; and I’ve translated the play script of a brilliant stage adaptation of Maria Jotuni’s Huojuva talo (“Tottering House”). Simon & Schuster just published my translation of Mia Kankimäki’s 450-page feminist travel memoir. I wouldn’t mind translating a comic novel by Veikko Huovinen. Of the classical works, though, I’m really only excited by Kivi and Kilpi; there’s a lot more Kilpi to translate, but I’ve translated almost all of what is great by Kivi. Perhaps one more play of his that would be fun to translate might be Olviretki Schleusingenissa (“Beer Expedition in Schleusingen”).

GS: You’ve written many books about translation. If you could synthesize that knowledge into a succinct piece of advice to translators worldwide, what would you say?

DR: Translation is a derivative art, yes, and it is ringed round with constraints; but translators have a lot more freedom than they have been taught to believe. We can take risks; we can push the envelope. You pay a price for that, certainly. As I say, it was very difficult to find a publisher for my Gulliver. One of the few rejections I got (as opposed to simply being ignored) said specifically that I draw too much attention to myself as the translator! I wasn’t sure Kilpi’s Gulliver was in the public domain, so I sent it to his grandson, who is in charge of his estate, asking permission to publish it—and was denied. Fortunately I did some more research and learned that the novel is indeed in the public domain—Kilpi died in 1939, and the required 70 years after that were up in 2009. So I wrote to Kilpi’s grandson to ask what the status of the estate’s denial was; he said it was a recommendation. So it can be a bit tricky pushing the envelope! But it can be done.

GS: Do you think translators get enough recognition? For instance, it’s not even a rule that a publisher must put the translator’s name on the book cover.

DR: In one sense, no, of course we don’t get enough recognition! The title of my very first book on translation, The Translator’s Turn, was a pun on two senses of turn: on the one hand, the translator turns from the source text into the target language, but like a bulldozer creating a new road turning into the woods; on the other, now it’s the translator’s turn to get recognized. And I do think that translators are increasingly getting the recognition they/we deserve! There’s a boom in translation these days. But in another sense the translator’s mandated invisibility lets us practice some ninja subversions. I’ve just submitted a dialogue on the avant-garde use of invisibility to Asymptote’s world literature special issue, arguing that the call for translators to be more visible, to get more recognition, is a call for a questionable kind of heroization, one that is problematically grounded in victim discourse. Poor put-upon us! That victim-heroism is also highly individualistic: I did it, I deserve credit for it! The avant-garde answer would be not only ninja subversion but participation in community. Fansubbers—crowd-sourced subtitling of movies and TV shows by fans who flout international copyright law—are participatory avant-garde translators in this sense. There’s a new concept in translation studies, “translaboration,” based on the idea that all translation is collaborative.

GR: Who are some of your favorite translators?

DR: Too many to name all of them! But I recently read Marian Schwartz’s brilliantly innovative translation of Mikhail Shishkin’s Maidenhair, and was blown away by it. I knew Marian back in the 1990s, when I was very active in the American Translators Association, and picked up the book when I saw that she had translated it. I have to say, though, that in admiring and loving the translation, I was also envious: if only someone would hire me to translate a book this brilliant, and specifically one that made so many mind-bending demands on the translator! Shortly after that, though, a publisher began to put out feelers for me to translate Yli-Juonikas’s Neuromaani, and I got very excited about that. So we’ll see.

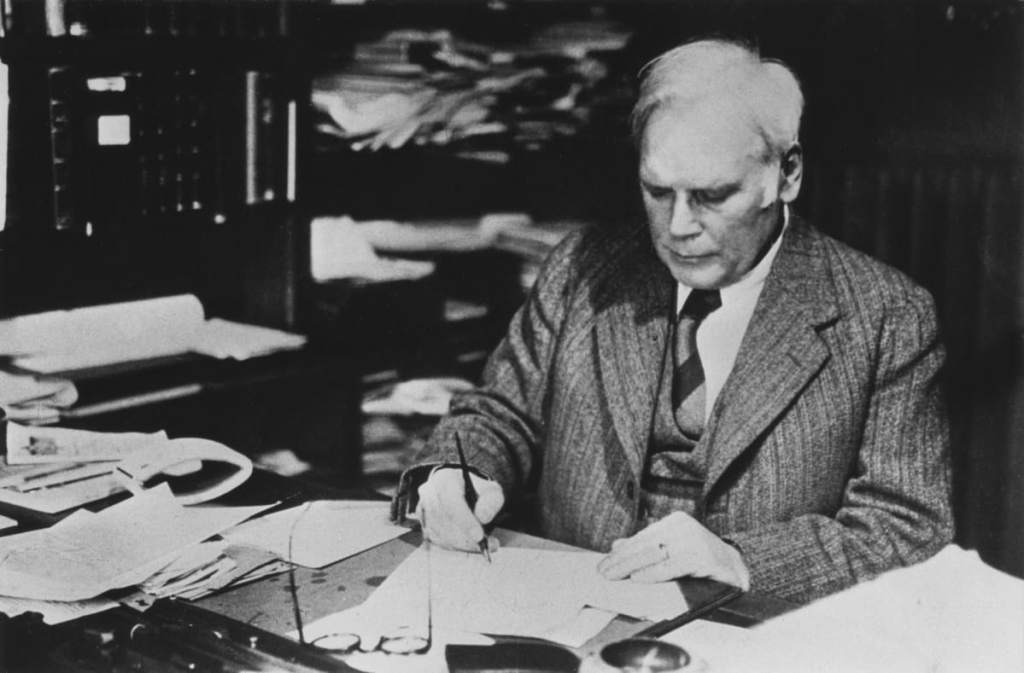

Douglas Robinson has been translating Finnish literature since 1975, when his Finnish girlfriend dragged him to a summer theater performance by this dead guy named Aleksis Kivi (1834-1872). Turned out he was the founder of Finnish-language literature and is still considered the greatest Finnish writer, or one of the two greatest, including Volter Kilpi. Kivi’s Finnish, Doug’s girlfriend warned him, is pretty difficult, so he might want to read the play (Nummisuutarit > “Heath Cobblers”) before they went. He did, and fell head over heels with Kivi’s writing. The performance was even more wonderful, and gave the words on the page brilliant comic body. When they returned from the play, Doug began rereading the play, and by some magic rereading turned into translating. Having translated all of Kivi’s greatest works—his three best plays and his exuberantly iconoclastic 1870 novel The Brothers Seven-—Doug turned to Finland’s other great novelist, Volter Kilpi, with a transcreation of Kilpi’s unfinished posthumously published novel Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia now and In the Alastalo Parlor in the hopefully not-too-distant future. Robinson is also considered one of the world’s leading translation scholars; his books include Aleksis Kivi and/as World Literature (Brill 2017), and he’s hard at work on another book tentatively titled Translating the Monster: Volter Kilpi in Orbit Beyond (Un)translatability.

George Salis is the author of Sea Above, Sun Below (River Boat Books / corona/samizdat). His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Zizzle Literary Magazine, House of Zolo, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. His criticism has appeared in Isacoustic, Atticus Review, and The Tishman Review, and his science article on the mechanics of natural evil was featured in Skeptic. He is currently working on an encyclopedic novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Instagram (@george.salis), and at www.GeorgeSalis.com.