Kachi-Buwa is a variable Katakana typeface expressing Japanese onomatopoeic expressions

Emi Takahashi investigates how a typeface can communicate the linguistic nuances of onomatopoeic Japanese expressions.

Meet

Emi Takahashi, the Toronto-based graphic designer and type designer

with a fascinating new project we can’t wait to tell you about. Having

recently graduated from OCAD University’s graphic design programme,

Emi’s practice delves into cultural, pedagogical and collaborative

themes. Born and raised in the Canadian city, she grew up closely

involved with her parent’s respective cultures, French and Japanese.

Heavily influenced by the multilingualism of her heritage, diverse

writing systems have always played a prominent role in Emi’s life. She

attended a school with a focus on languages during the week, then, on

weekends she went to Japanese school.

There, she was introduced to the art of Shodō – traditional Japanese calligraphy – and its rich philosophy which goes hand in hand with the writing form. Taught by a “tremendously passionate and skilled teacher,” Emi came to understand that letterforms are so much more than a tool of communication. She tells us, “it could also be a craft and a field of study.” In turn, typography has since been a constant interest for Emi, a medium she returned to time and time again throughout her graphic design studies.

Her interest in type has most recently culminated in a project titled Kachi-Buwa. “It investigates how design can communicate the nuances in connotations and culture-specific context expressed by onomatopoeia in the Japanese language,” she tells us. Onomatopoeic words, she reminds us, are an interesting exception in linguistics where words non-arbitrarily bind sound with meaning. “They are often the first classes of words one encounters as a child,” says Emi, “from animal sounds such as ‘moo’, ‘meow’ and ‘woof’ to noises such as bang, boom or pop” which are all words formed from the sounds they are associated with.

There, she was introduced to the art of Shodō – traditional Japanese calligraphy – and its rich philosophy which goes hand in hand with the writing form. Taught by a “tremendously passionate and skilled teacher,” Emi came to understand that letterforms are so much more than a tool of communication. She tells us, “it could also be a craft and a field of study.” In turn, typography has since been a constant interest for Emi, a medium she returned to time and time again throughout her graphic design studies.

Her interest in type has most recently culminated in a project titled Kachi-Buwa. “It investigates how design can communicate the nuances in connotations and culture-specific context expressed by onomatopoeia in the Japanese language,” she tells us. Onomatopoeic words, she reminds us, are an interesting exception in linguistics where words non-arbitrarily bind sound with meaning. “They are often the first classes of words one encounters as a child,” says Emi, “from animal sounds such as ‘moo’, ‘meow’ and ‘woof’ to noises such as bang, boom or pop” which are all words formed from the sounds they are associated with.

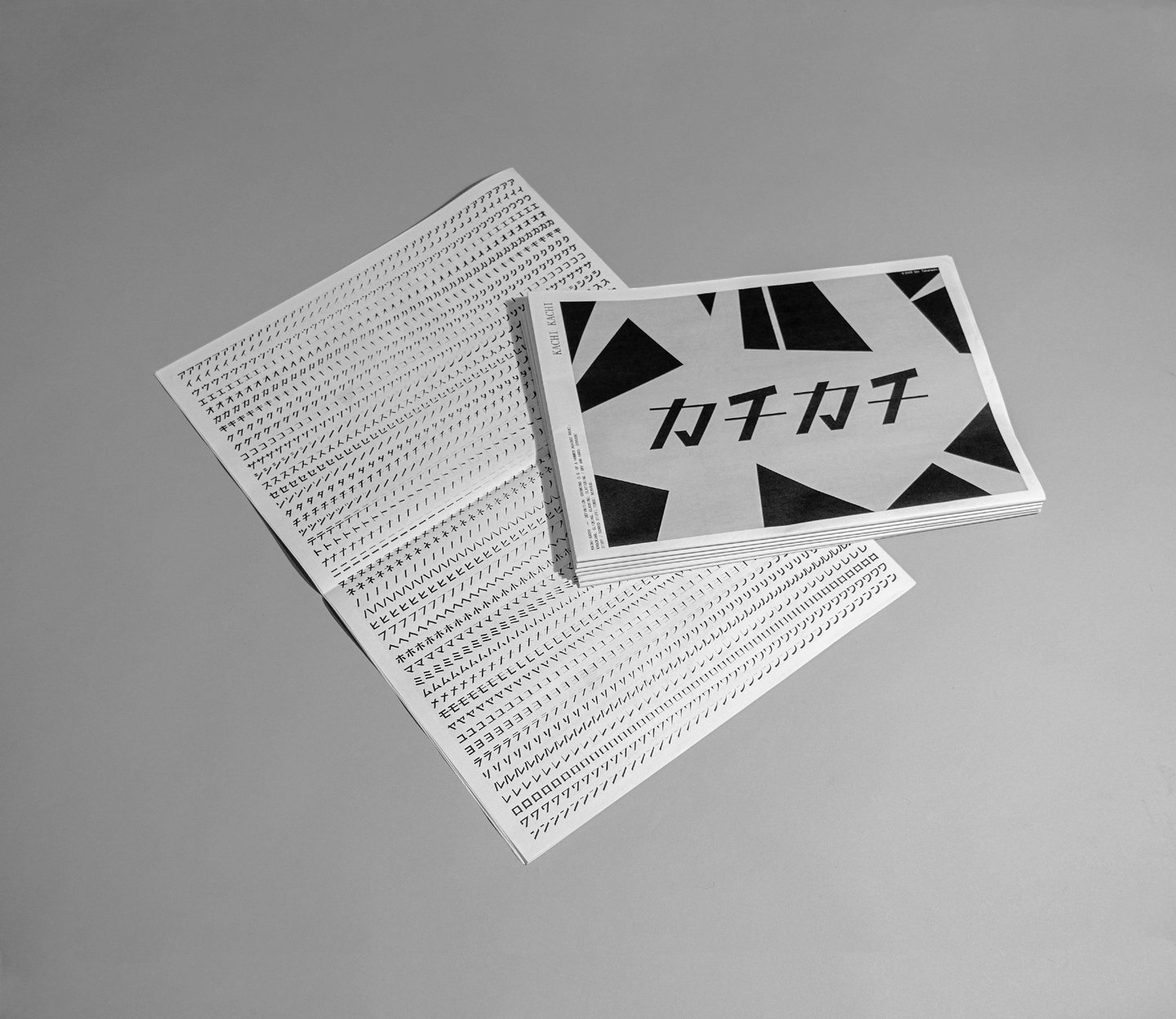

Above

Kachi-Buwa (Copyright © Emi Takahashi 2020)

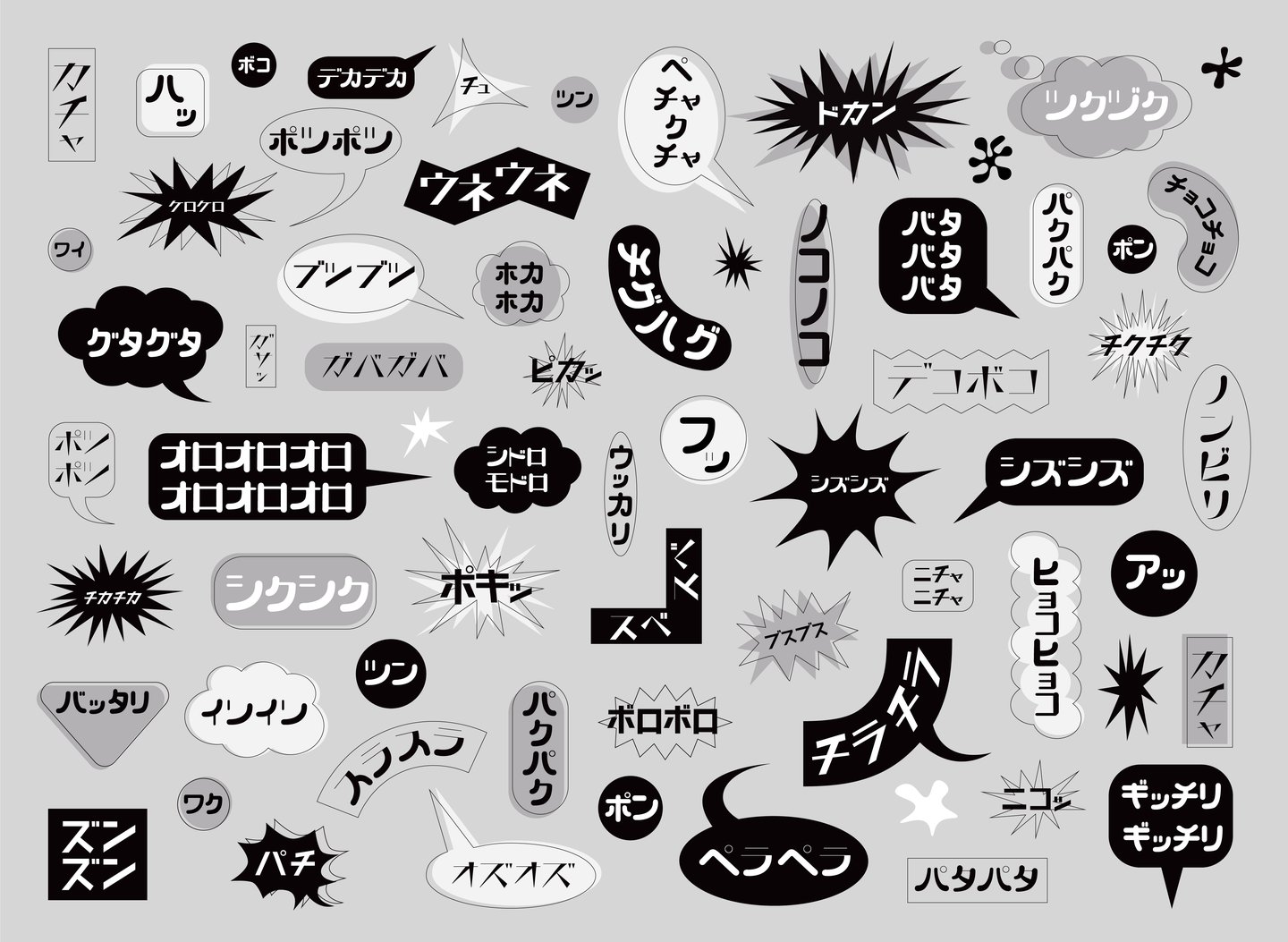

Japanese

onomatopoeias however, take this even further as many of the words also

convey sensory experiences and human-made concepts. To describe the

feeling of stickiness for example, there are a variety of nuanced

expressions: “nuru nuru, neto neto, neba neba, beto beto, beta beta,”

Emi points out. Alternatively, there are many Japanese onomatopoeic

expressions which communicate emotional or psychological states of mind

that are hard to get across with descriptive terms. It’s an elaborate

and rich symbolic sound system, consisting of more than 4500 expressions

which, Emi explains, “makes a visceral kind of communication possible.”

“When I listened to these expressions,” the designer continues, “absorbing their meanings was for me, akin to ‘reading the air’ or kuuki wo yomu, which is a collective cultural understanding of context particular to Japanese culture where one can understand a situation without words. I found this both fascinating and intriguing, and I sought to explore a typographic interpretation.” As a result, Kachi-Buwa is a conceptual variable Katakana typeface which aims at bridging sound, form and signification while being simultaneously embedded in Japanese visual culture.

Delving into a four month long research phase, Emi kicked off the project with a deep dive into both Eastern and Western usages of onomatopoeia and its etymological, linguistic, historical and semantic perspectives; not to mention their relationship to one another. Another prominent branch of her research involved looking into more modern typoraphic technologies, more namely, the variable typeface.

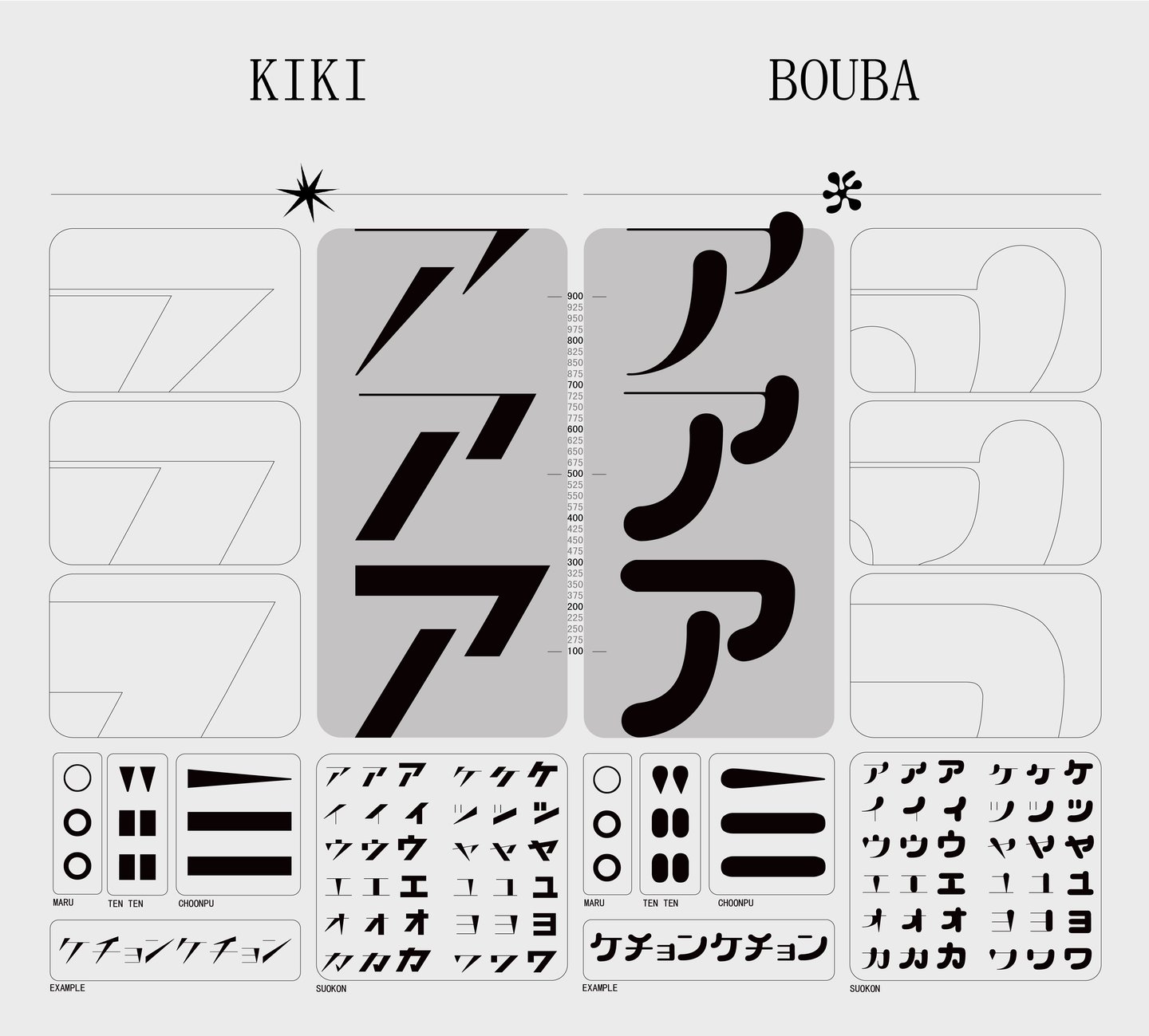

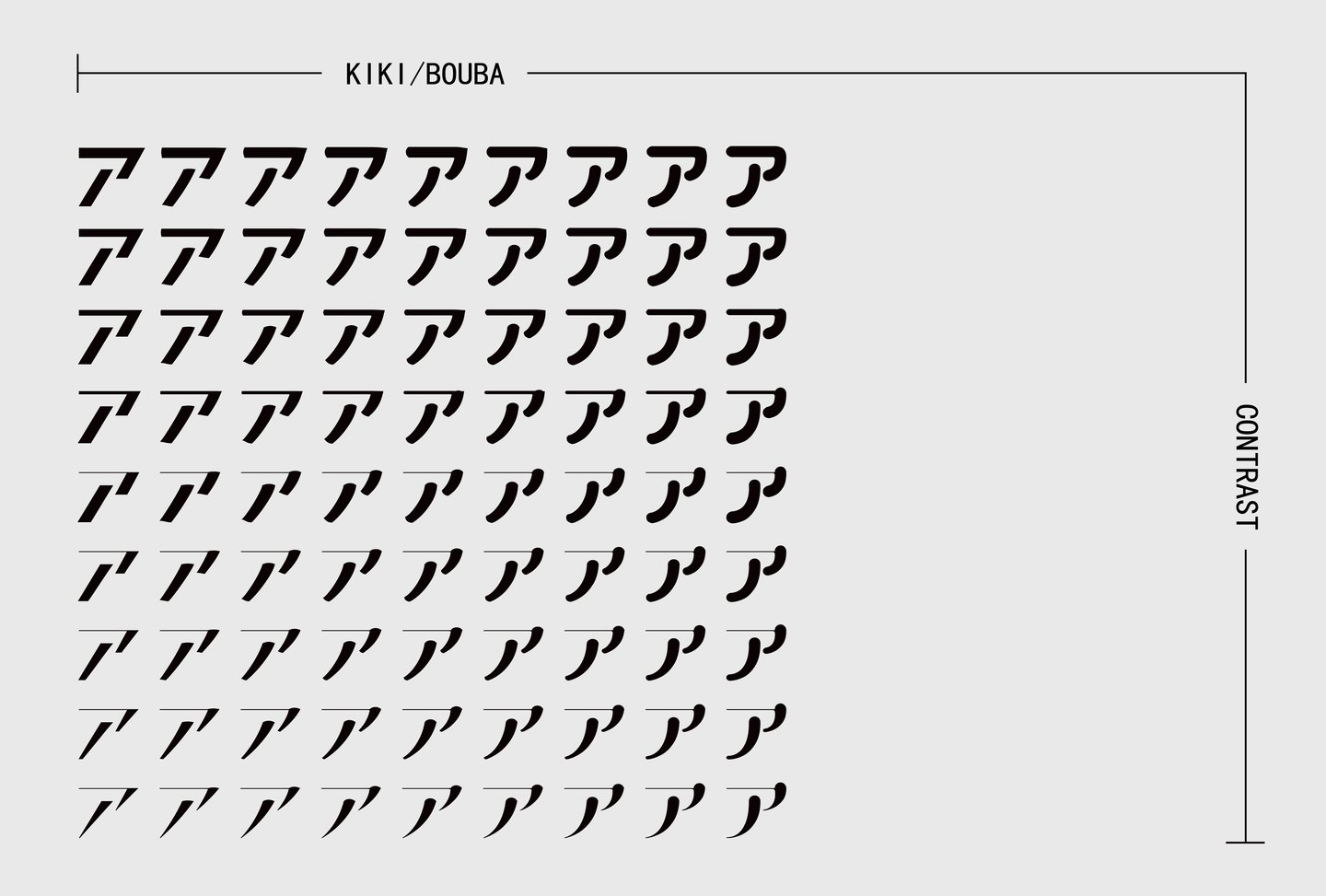

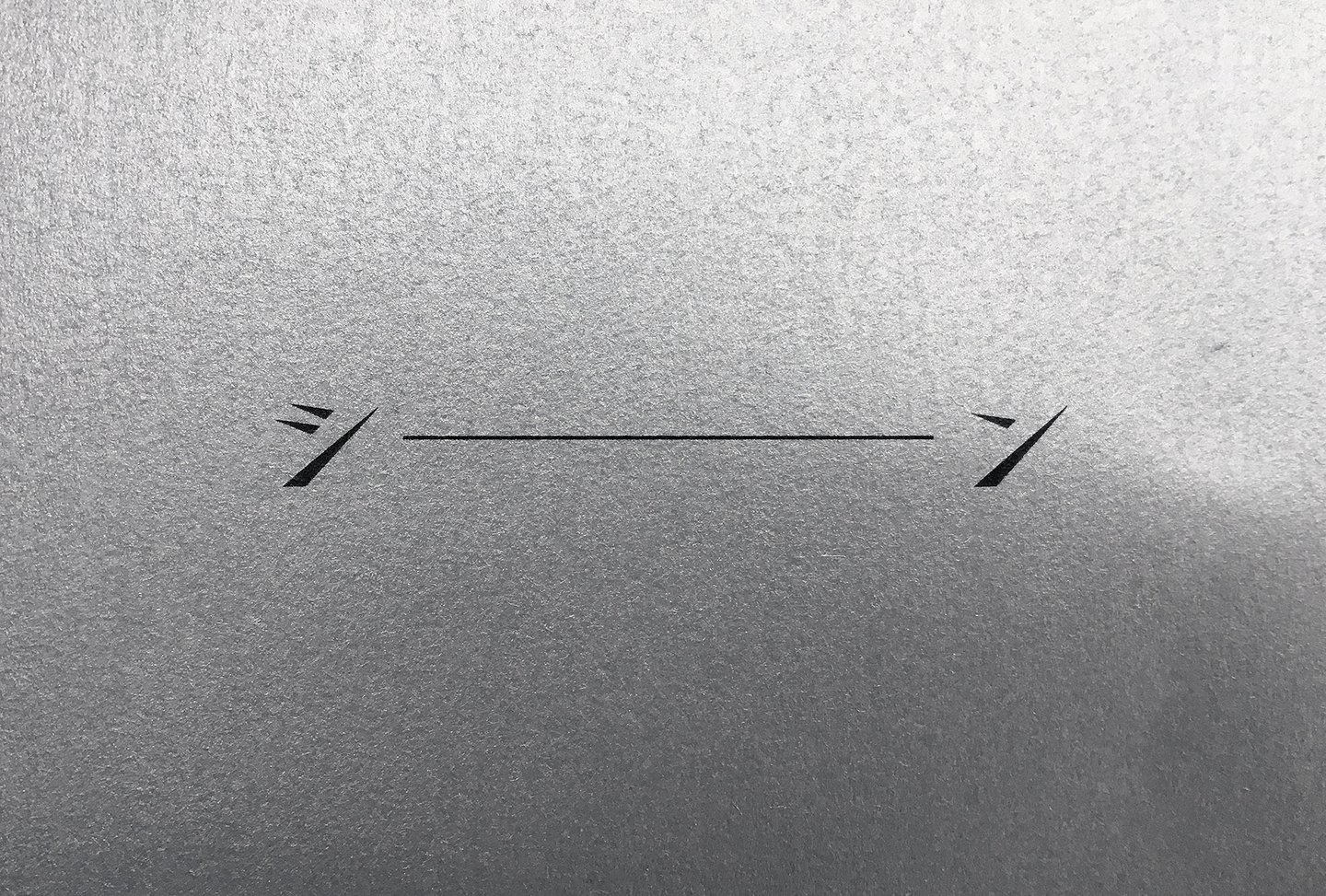

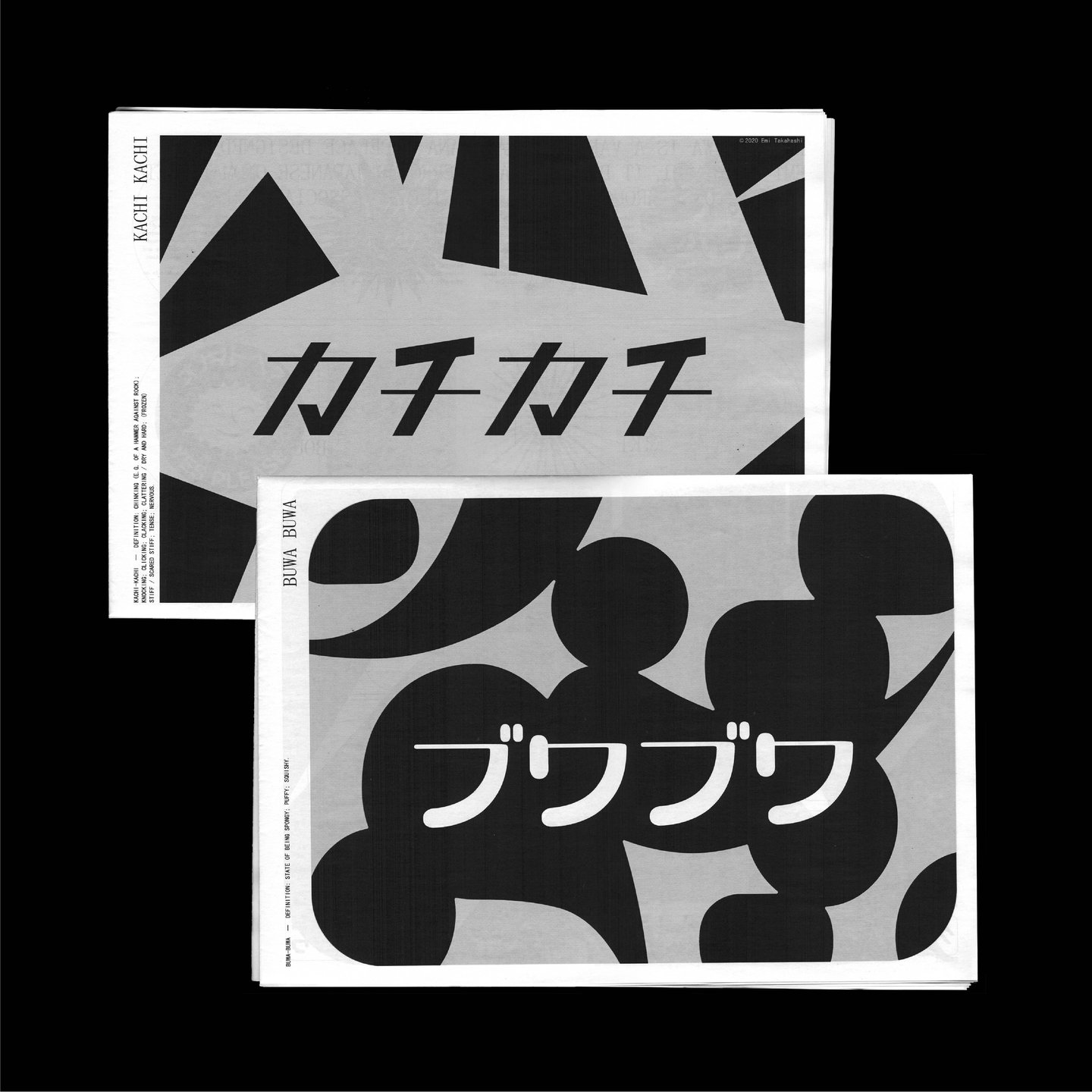

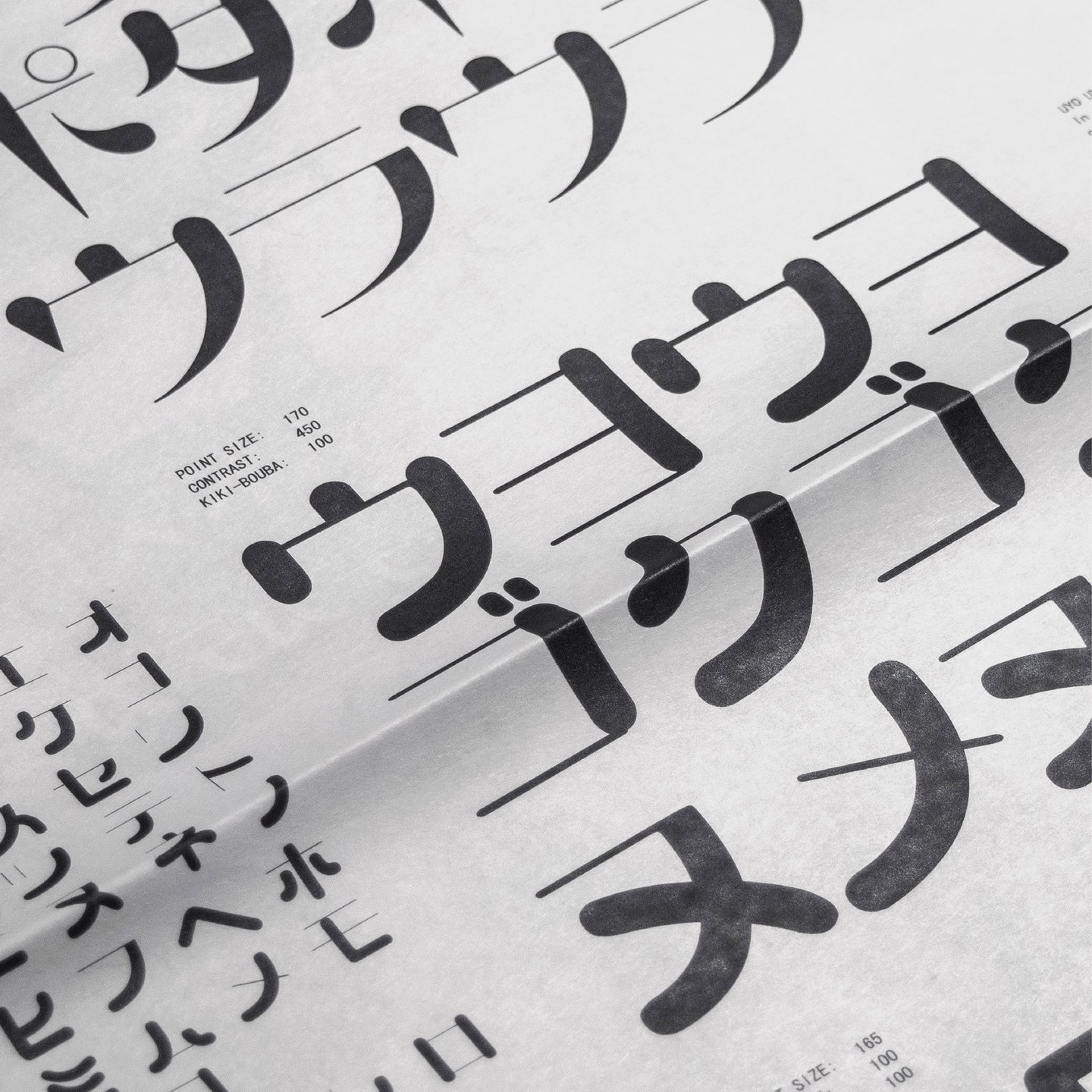

Coupling this research together, Emi went onto create her own variable Katakana font, a demonstration of the non-arbitrary relationship between sound and form; otherwise known as the “Kiki-Bouba effect.” This effect entails the instinctive visualisation of the two words “Kiki” and “Bouba.” Due to the spiky shape of the former, “Kiki” is often mapped out with rigidity as opposed to rounded shapes which form the word “Bouba”.

In a similar way, the name of Emi’s typeface is Kachi-Buwa, “a playful invention borrowing from Japanese onomatopoeias whose meaning and sound evoke the “Kiki” and “Bouba” concept. She demonstrates as she concludes: “kachi kachi (カチカチ) describes sharp, rambunctious sounds, the state of stiffness as well as feelings of nervousness whereas buwa buwa (ブワブワ) is the state of being spongy, puffy or squishy.”

“When I listened to these expressions,” the designer continues, “absorbing their meanings was for me, akin to ‘reading the air’ or kuuki wo yomu, which is a collective cultural understanding of context particular to Japanese culture where one can understand a situation without words. I found this both fascinating and intriguing, and I sought to explore a typographic interpretation.” As a result, Kachi-Buwa is a conceptual variable Katakana typeface which aims at bridging sound, form and signification while being simultaneously embedded in Japanese visual culture.

Delving into a four month long research phase, Emi kicked off the project with a deep dive into both Eastern and Western usages of onomatopoeia and its etymological, linguistic, historical and semantic perspectives; not to mention their relationship to one another. Another prominent branch of her research involved looking into more modern typoraphic technologies, more namely, the variable typeface.

Coupling this research together, Emi went onto create her own variable Katakana font, a demonstration of the non-arbitrary relationship between sound and form; otherwise known as the “Kiki-Bouba effect.” This effect entails the instinctive visualisation of the two words “Kiki” and “Bouba.” Due to the spiky shape of the former, “Kiki” is often mapped out with rigidity as opposed to rounded shapes which form the word “Bouba”.

In a similar way, the name of Emi’s typeface is Kachi-Buwa, “a playful invention borrowing from Japanese onomatopoeias whose meaning and sound evoke the “Kiki” and “Bouba” concept. She demonstrates as she concludes: “kachi kachi (カチカチ) describes sharp, rambunctious sounds, the state of stiffness as well as feelings of nervousness whereas buwa buwa (ブワブワ) is the state of being spongy, puffy or squishy.”

Above

Kachi-Buwa (Copyright © Emi Takahashi 2020)

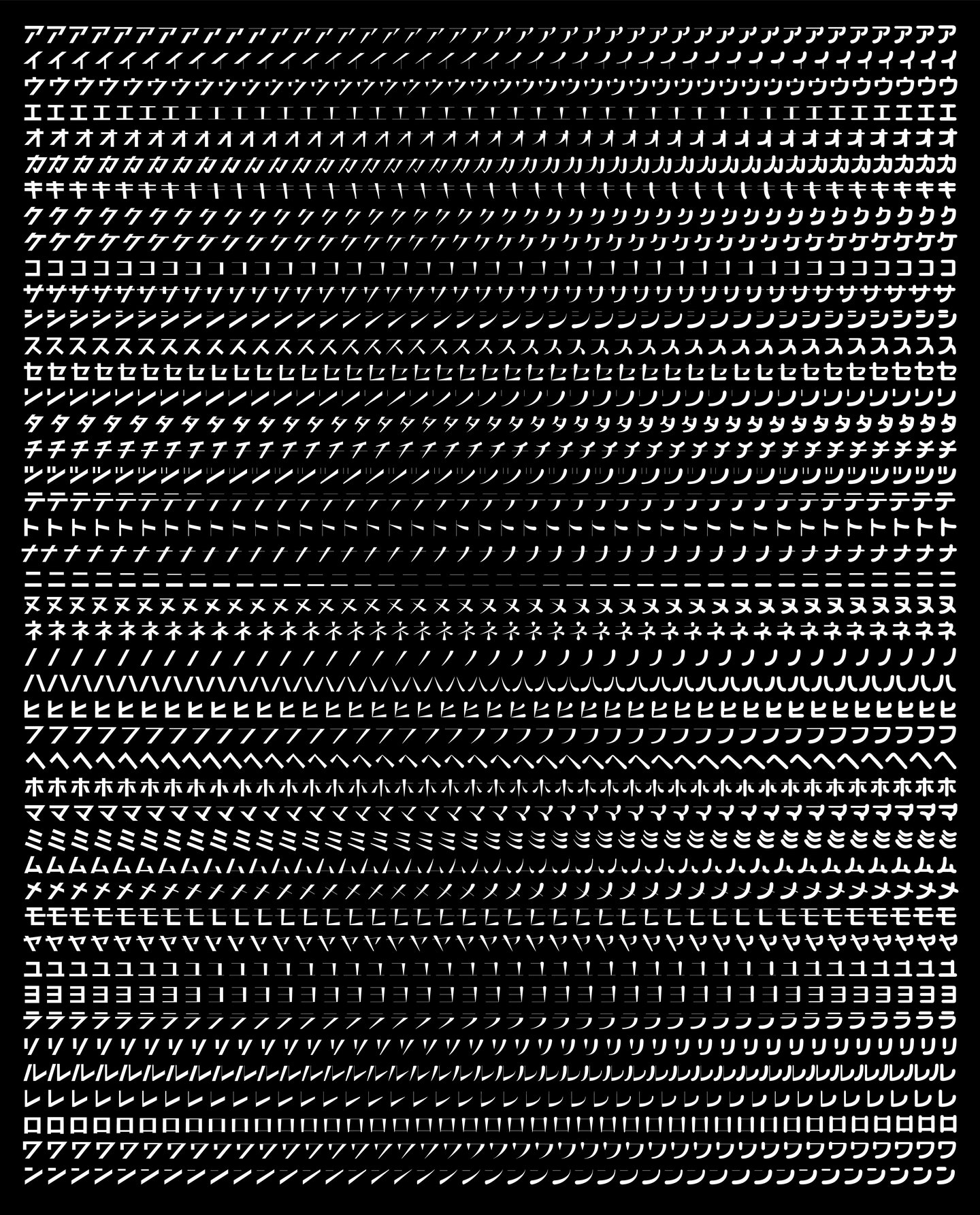

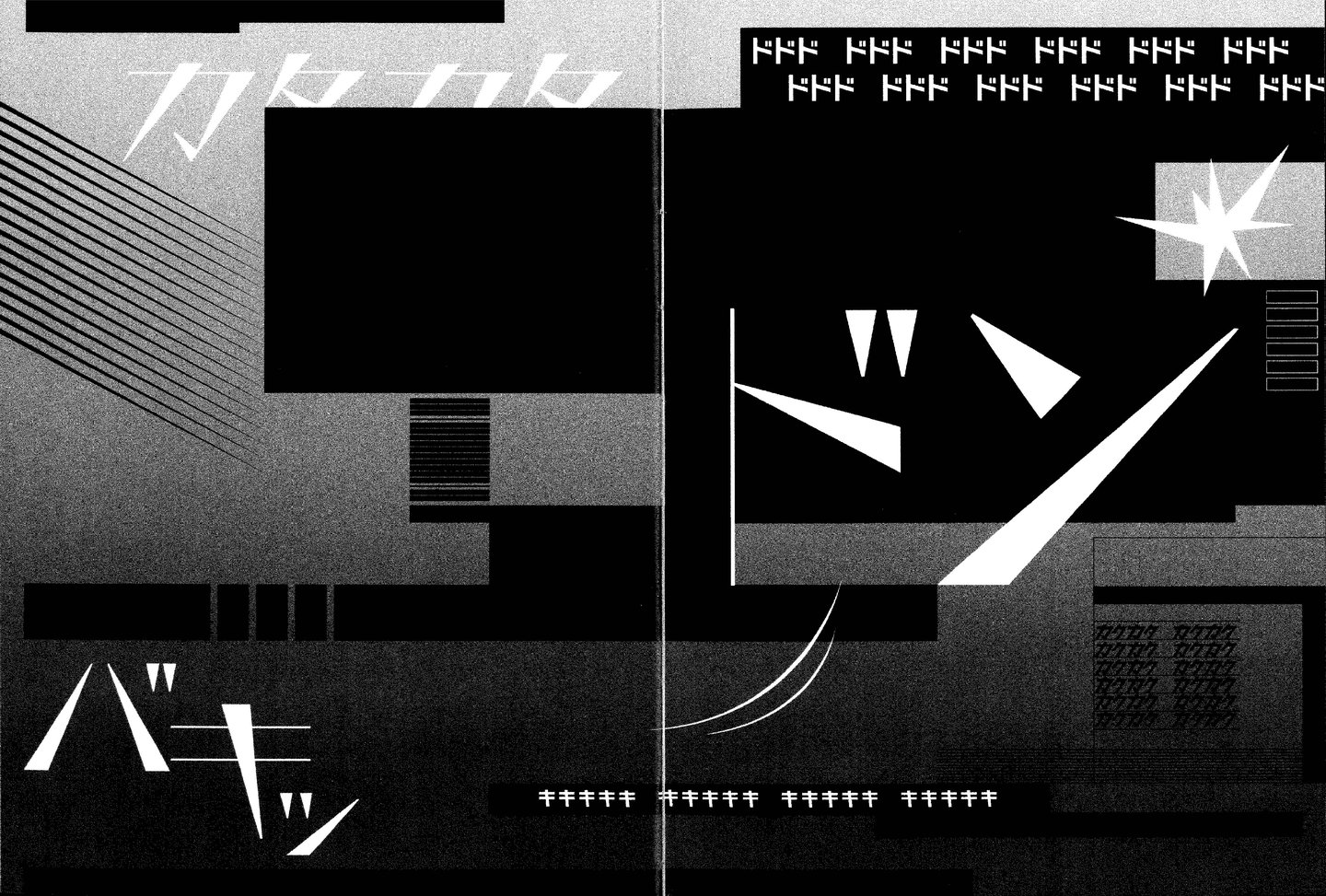

Kachi-Buwa

therefore, is highly original and innovative is its ability to capture

the “kikiest” and “boubaest” of Japanese onomatopoeic expressions and

anything else in between. Mapped out on two variable axis which visually

express these ideas, Kachi-Buwa can create a near-infinite range of

typographic variations that grant a wholly unique form of communication.

Currently, the typeface includes 46 regular Katakana, 12 small Katakana

and three diacritics, generating a total of 84 distinct glyphs. Without

the use of the variable font tool, the typeface impressively consists

of 504 unique glyphs evidenced in a range of mini projects also designed

by Emi including the likes of a newspaper, zine, poster, storybook and

onomatopoeic music video.

By no means a simple undertaking, this extensive project has allowed Emi “to insert a rich and under-recognised brand of both traditional and modern Japanese culture into a present-day design discourse.” Merging sound, meaning and form through harmonious type design, Kachi-Buwa is both light hearted in nature yet unconstrained in its expression. Finally, the designer goes on to say, “I hope that this introduction to Japanese onomatopoeia can offer audiences a lesson in synaesthetic articulation and spark with curiousity and a sense of wonder for the very nature of language.”

Currently worked at the design studio Frontier, Emi hopes to continue working on Kachi-Buwa in the future in an attempt to exhaust all its possibilities including its performative and poetic potentials. She’s also keen to explore the realms of publishing with the hopes of democratising the media’s access and encouraging diverse discourses.

By no means a simple undertaking, this extensive project has allowed Emi “to insert a rich and under-recognised brand of both traditional and modern Japanese culture into a present-day design discourse.” Merging sound, meaning and form through harmonious type design, Kachi-Buwa is both light hearted in nature yet unconstrained in its expression. Finally, the designer goes on to say, “I hope that this introduction to Japanese onomatopoeia can offer audiences a lesson in synaesthetic articulation and spark with curiousity and a sense of wonder for the very nature of language.”

Currently worked at the design studio Frontier, Emi hopes to continue working on Kachi-Buwa in the future in an attempt to exhaust all its possibilities including its performative and poetic potentials. She’s also keen to explore the realms of publishing with the hopes of democratising the media’s access and encouraging diverse discourses.

GalleryKachi-Buwa (Copyright © Emi Takahashi 2020)

© It’s Nice That 2020 · Nice Face Logo © It’s Nice That

Designed & Developed by Bureau for Visual Affairs

Designed & Developed by Bureau for Visual Affairs