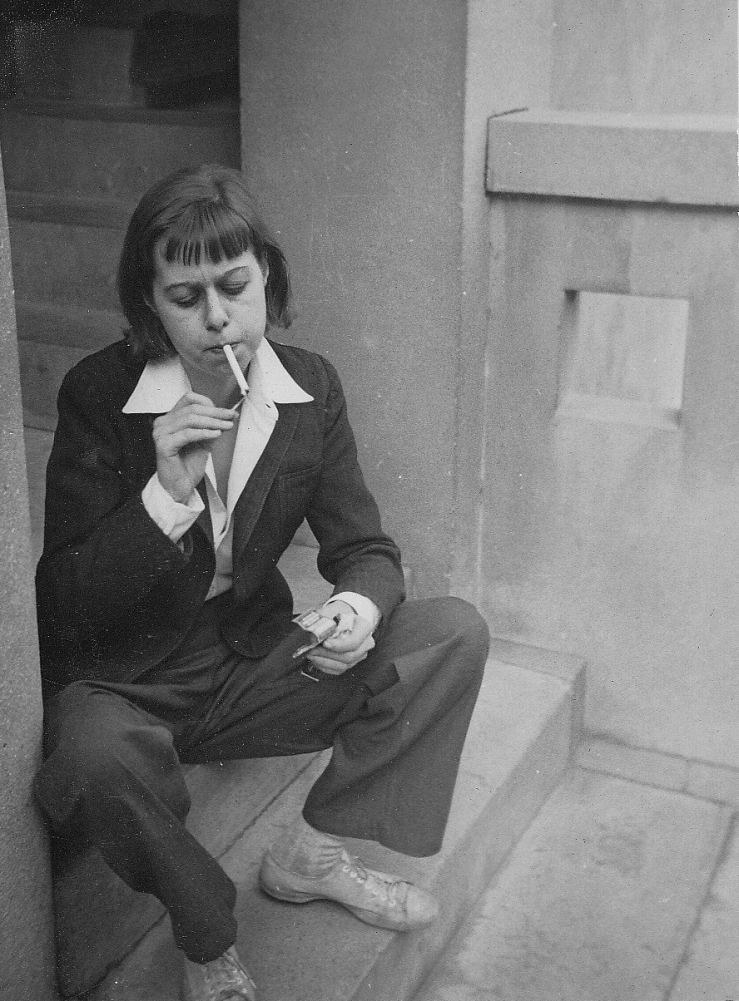

A riff on rereading Carson McCullers’ novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

- I’m not really sure what made me pick up Carson McCullers’ 1940 début novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter to read again.

- Actually, writing that sentence makes me remember: I was purging books, and the edition I have is extremely unattractive; I was considering trading it in. But I started reading it, realizing that I hadn’t reread it ever, that I hadn’t read it since I was probably a senior in high school or maybe a college freshman.

- So it was maybe two decades ago that I first read it. I would’ve been maybe 18, about five years younger than McCullers was when the novel was published (and not much older than its protagonist Mick Kelly). The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter never stuck with me like The Ballad of the Sad Café or her short stories did, but I remember at the time thinking it far superior to Faulkner—more lucid in its description of the Deep South’s abjection. (I struggled with Faulkner when I was young, but now see his tangled sentences and thick murky paragraphs are a wholly appropriate rhetorical reckoning with the nightmare of Southern history).

- And of course I preferred Flannery O’Connor to both at the time—her writing was simultaneously lucid and acid, cruel and funny. Maybe I still like her best of the three.

- O’Connor, in a 1963 letter: “I dislike intensely the work of Carson McCullers.”

- O’Connor again:

When we look at a good deal of serious modern fiction, and particularly Southern fiction, we find this quality about it that is generally described, in a pejorative sense, as grotesque. Of course, I have found that anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the Northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.

- The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter is at its best when it is at its most grotesque, which is to say, most realistic.

- Here’s a sample of that grotesque dirty realism from very late in

the book, as Jake Blount (an alcoholic and would-be revolutionary)

departs the small, unnamed Georgia town that the novel is set in—and the

narrative:

The door closed behind him. When he looked back at the end of the black, Brannon was watching from the sidewalk. He walked until he reached the railroad tracks. On either side there were rows of dilapidated two-room houses. In the cramped back yards were rotted privies and lines of torn, smoky rags hung out to dry. For two miles there was not one sight of comfort or space or cleanliness. Even the earth itself seemed filthy and abandoned. Now and then there were signs that a vegetable row had been attempted, but only a few withered collards had survived. And a few fruitless, smutty fig trees. Little younguns swarmed in this filth, the smaller of them stark naked. The sight of this poverty was so cruel and hopeless that Jake snarled and clenched his fists.

- The passage showcases some of McCullers’ best and worst prose tendencies. Her evocation of the South’s rural poverty condenses wonderfully in the image of “a few fruitless, smutty fig trees” — smutty!—but there’s also an underlying resort to cliché, into placeholders — “stark naked”; “clenched his fists.”

- (Maybe you think I’m picking on McCullers here, yes? Not my intention. I’ll confess I read a career-spanning compendium of Barry Hannah’s short stories, Long, Last, Happy right before I read The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, and McCullers simply can’t match sentences with Our Barry. It’s an unfair comparison, sure. But).

- But McCullers was only 23 when The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter was published. Stock phrases must be forgiven, yes? Yes.

- And there are plenty of great moments on the page, like this one, in

which (McCullers’ stand-in) Mick Kelly tries her young hand at writing:

The rooms smelled of new wood, and when she walked the soles of her tennis shoes made a flopping sound that echoed through all the house. The air was hot and quiet. She stood still in the middle of the front room for a while, and then she suddenly thought of something. She fished in her pocket and brought out two stubs of chalk—one green and the other red. Mick drew the big block letters very slowly. At the top she wrote EDISON, and under that she drew the names of DICK TRACY and MUSSOLINI. Then in each corner with the largest letters of all, made with green and outlined in red, she wrote her initials—M.K. When that was done she crossed over to the opposite wall and wrote a very bad word—PUSSY, and beneath that she put her initials, too. She stood in the middle of the empty room and stared at what she had done. The chalk was still in her hands and she did not feel really satisfied.

Who is ever really satisfied with their own writing though?

- We’re several hundred words into this riff and I’ve failed to summarize the plot of The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. There really isn’t a plot per se, actually—sure, there are a development of ideas, themes, motifs, characters—yep—and sure, lots of things happen (the novel is episodic)—but there isn’t really a plot.

- The point above is absurd. Of course there is a plot, one which you could easily diagram in fact. Such a diagram would describe the sad strands of four misfits gravitating toward the deaf-mute, John Singer, the silent center of this sad novel. These sad strands tangle, yet ultimately fail to cohere into any kind of harmony with each other. Even worse, these strands fail to make a true connection with Singer. The misfits all essentially use him as a sounding board, a mute confessional booth. They think they love him, but they love his silence, they love his listening. They don’t learn about his own strange love and his own strange sadness.

- Or, if you really want to oversimplify plot: The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

is about growing up. In a novel with a number of tragic trajectories,

it’s somehow the ending of the Mick Kelly thread that I found most

affecting. She still dreams of making great grand music, of writing

songs the world would love—but McCullers leaves her standing on her feet

working overtime in Woolworth’s to get her family out of the hole. This

is the curse of adulthood, of grasping onto dreams even as the

world flattens them out into a big boring nothing. The final lines

McCullers gives her, via the novel’s free indirect style, strike me as

ambiguous:

…what the hell good had it all been—the way she felt about music and the plans she had made in the inside room? It had to be some good if anything made sense. And it was too and it was too and it was

too and it was too. It was some good.

All right!

O.K!

Some good. - Is Mick’s self-talk here a defense against disillusionment—one haunted by the truth of life’s awful boring ugliness—or a genuine earnest rallying against the ugliness—or perhaps a mix of both? “Some good” can be read both ironically and earnestly.

- Its navigation of irony and earnestness is where I find the novel most off balance. There’s a clumsy cynicism to The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter—a justified cynicism, to be sure, given its themes of racism, classicism, modern alienation—but McCullers’ approach to sussing out her big themes is often heavy-handed. Too often characters’ speeches and dialogues—particularly those of the working-class socialist Blount and Dr. Copeland, a black Marxist—feel forced. Entire dialectics that seem lifted from college lecture notes are shoved into characters’ mouths. Still: if I sometimes found such moments insufferable, McCullers nevertheless reminded me that she was pointedly addressing suffering.

- The earnestness there is mature, but the cynicism isn’t. I’m not quite sure what I mean by this—the cynicism isn’t deep? The cynicism is a pose, a viewpoint not fully, but nevertheless freshly, lived in. The cynicism is the cynicism that some of us like to try on when we’re 18, 19, 20, 21.

- And re: the point above—that’s good, right? I mean it’s good that McCullers channeled this pure and very real anger into her novel. Maybe I failed the novel, this time, in rereading it twenty years later and thinking repeatedly, But that’s the way the world is: Often awful and almost always unfair. Blount and Copeland are interesting but essentially paralyzed characters; they howl against injustice but McCullers can only make them act in modes of ineffective despair.

- Despair. This is a sad novel—a realistically sad novel, a grotesquely sad novel—sympathetic but never sentimental. (We Southerners love sugar and sentiment; bless her heart, McCullers cuts any hint of the latter out. And if Mick Kelly enjoys an ice cream sundae for her last dinner in the novel, note that she chases it with a bitter beer that gets her just drunk enough to keep going).

- But some of us like to laugh at and with despair, and The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter serves up a big bitter brew without a heady or hearty laugh to help you swallow it down. The novel’s humorlessness was perhaps by design—these characters dwell in absurd abjection. But absurdity often calls for a laugh, and laughter is not always sugar sweetness, but rather can be a reveling in bitterness—perhaps what I mean here, is that laughter is a sincere and deep reckoning with mature cynicism.

- I quoted O’Connor above, in point six; in the same lecture, she warned against writers (particularly Southern writers) giving into the need of the “tired reader…to be lifted up.” O’Connor often forced her characters into moments of radical redemption, moments that complicate her “tired reader’s” desire to have his “senses tormented or his spirits raised.” This modern reader, according to O’Connor, “wants to be transported, instantly, either to mock damnation or a mock innocence.” For O’Connor, the modern reader’s “sense of evil is diluted or lacking altogether, and so he has forgotten the price of restoration.” Restoration in O’Connor’s fiction is always purchased at a heavy cost—many readers can only see the cost, and not the redemption in her calculus.

- And restoration in The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter? Perhaps the novel’s greatest strength is its lack of sentimentality, its unwillingness to restore its characters to a mythical Eden. Indeed, McCullers’ setting never even posits a grace from which her characters might fall. Instead, the novel’s final moments leave us “suspended between radiance and darkness. Between bitter irony and faith.” Any restoration is impermanent, as the final line suggests: “And when at last he was inside again he composed himself soberly to await the morning sun.” If the morning sun promises a new tomorrow, a futurity, that futurity is nevertheless conditioned by the need to repeatedly “compose” oneself into a new being, always under the duress of “bitter irony and faith.” McCullers’ plot might side with bitter irony, but her belief in her characters’ beliefs—belief in the powers of art, politics, and above all love—point ultimately to an earnest faith in humanity to compose itself anew.