From cut-out confessions to cheese pages: browse the world's strangest books

Edward

Brooke-Hitching set out to curate the ultimate collection of bizarre

books down the ages. He leads us around the Madman’s Library

Edward Brooke-Hitching grew up in a rare book shop, with a rare book dealer for a father. As the author of histories of maps The Phantom Atlas, The Golden Atlas and The Sky Atlas, he has always been “really fascinated by books that are down the back alleys of history”. Ten years ago, he embarked on a project to come up with the “ultimate library”. No first editions of Jane Austen here, though: Brooke-Hitching’s The Madman’s Library collects the most eccentric and extraordinary books from around the world.

“I was asking, if you could put together the ultimate library, ignoring the value or the academic significance of the books, what would be on that shelf if you had a time machine and unlimited budget?” he says.

Following up anecdotes, talking to booksellers and librarians and trawling through auction catalogues, he came across stories like that of the 605-page Qur’an written in the blood of Saddam Hussein. “If that was on a shelf, what could possibly sit next to it?” he asks. “I mentioned it to a bookseller and they told me about a diary that they’d had, from the 19th century, written by a shipwrecked captain who only had old newspaper and penguins to hand. So Fate of the Blenden Hall was written entirely in penguin blood.”

There’s the American civil war soldier who inscribed his journal of the conflict on to the violin he carried. There’s the memoir of a Massachussetts highwayman, James Allen, which he “requested be bound in his own skin after his death, and presented to his one victim who had fought back as a token of his admiration”. Or the diary of the Norwegian resistance fighter Petter Moen, pricked with a pin into squares of toilet paper and left in a ventilation shaft; although Moen was killed in 1944, one of his fellow prisoners returned to Oslo after it was liberated from the Nazis and found the diary. Or the entirely fabricated book An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa: its author George Psalmanazar, a blond-haired, blue-eyed, pale-skinned man with a thick French accent, arrived in London in about 1702 and declared himself to be the first Formosan, or Taiwanese, person to set foot on the European continent. (“Obviously no one had been there and nobody knew what Taiwanese people looked like, and he became the toast of high society,” says Brooke-Hitching.)

The joy for the author in his discoveries – and make no mistake, The Madman’s Library is an utterly joyous journey into the deepest eccentricities of the human mind – was that they “make you realise that, above everything, people have always been funny, been weird, been unquenchably curious in every possible arena”.

The best way, he says, to understand the people of the past is in “getting a sense of the things that make them giggle … It can be gruesome, but it’s this other world of literature that normally never gets covered in books about books.”

10 of the strangest books, selected by Edward Brooke-Hitching

Saddam Hussein’s Blood Qur’an (circa 1999)

On his 60th birthday in 1997, the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein commissioned the master calligrapher Abbas Shakir Joudi al-Baghdadi to produce a Qur’an written in Hussein’s blood. Over a period of two years, somewhere between 24 and 27 litres was allegedly drained from the dictator and mixed with chemicals to produce enough “ink” to write out the 336,000 words in 6,000 verses. Exquisitely beautiful, the Blood Qur’an was eventually displayed in another of Hussein’s enterprises, the Umm al-Ma’arik (Mother of All Battles) mosque in Baghdad.

After the fall of Baghdad, the Blood Qur’an was hastily stored away by curators until they could decide how to deal with it, as it presented a dilemma: while it is haraam (forbidden) to reproduce a Qur’an in such a manner, it is equally unthinkable to destroy a Qur’an, regardless of how it was made. At the time of writing, the dilemma is unresolved. In 2010, the Iraqi prime minister’s spokesman, Ali al-Moussawi proposed that the Blood Qur’an should be kept “as a document of the brutality of Saddam”, but it remains out of sight, hidden in a vault to which there are three keys, each held by a separate public official, none with any idea of what to do with the extraordinary book.

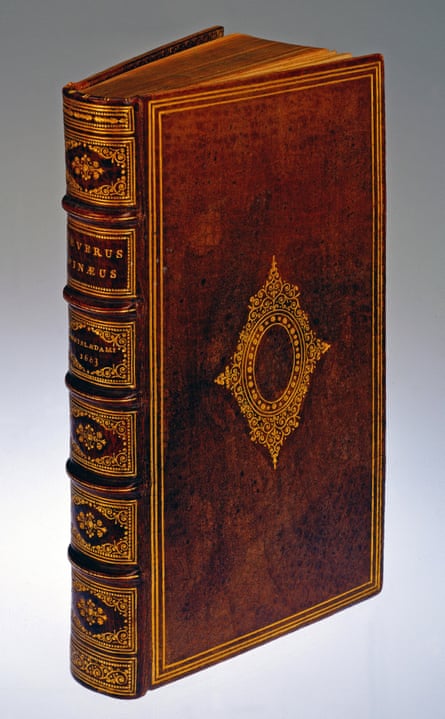

De integritatis et corruptionis virginum by Séverin Pineau (1663)

This treatise on virginity, pregnancy and childbirth was printed in Amsterdam. The book’s owner, Dr Ludovic Bouland, explains in a note: “This curious little book ... has been re-dressed in a piece of the skin of a woman tanned for myself.” As unthinkably weird as it is to modern sensibilities, in Europe and the US, mostly in the 18th and 19th centuries, binding a book in human skin became an acceptable decorative extra when publishing accounts of murderers’ crimes and medical studies. Towards the end of the 19th century it morphed into more of a romantic metaphor, to encapsulate great writing in flesh just as the mortal body encloses the soul. (A human-skin book was also, frankly, a great thing to show off at parties.)

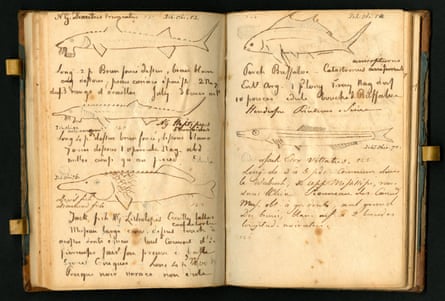

Book 17th of Notes – Travels in 1818 by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1818)

In 1818, the French natural historian Rafinesque travelled to Kentucky to visit fellow naturalist John James Audubon. Rafinesque became such an irritating house guest that Audubon started to make up local animals to make fun of him, which the Frenchman faithfully recorded and sketched without question. Here there are four fake fish: the “Flatnose Doublefin”, the “Bigmouth Sturgeon”, the “Buffalo Carp Sucker” and the bulletproof “Devil-Jack Diamond fish”.

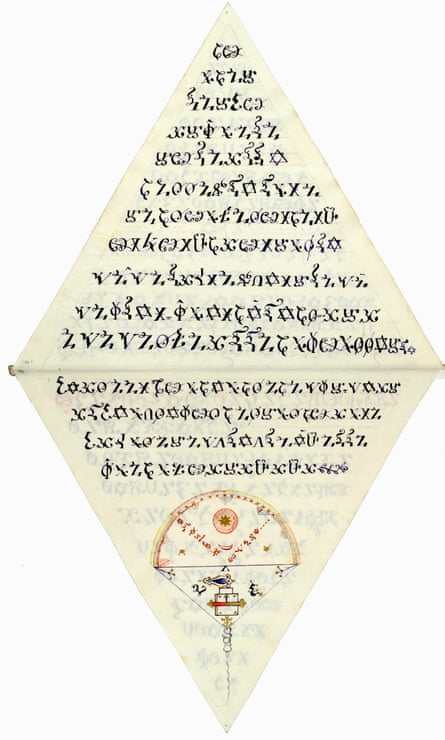

The Triangular Book of Count St Germain (circa 1750)

This is an encoded French occult work which boasts the secret to extending life. The mysterious and eccentric Count St Germain was an adventurer and alchemist who thrilled 18th-century Europe’s high society with his claim to have uncovered the secret to longevity. He was so old, he said, that he had attended the wedding at Cana where Jesus turned water to wine. Horace Walpole wrote of him: “He sings, plays on the violin wonderfully, composes, is mad.”

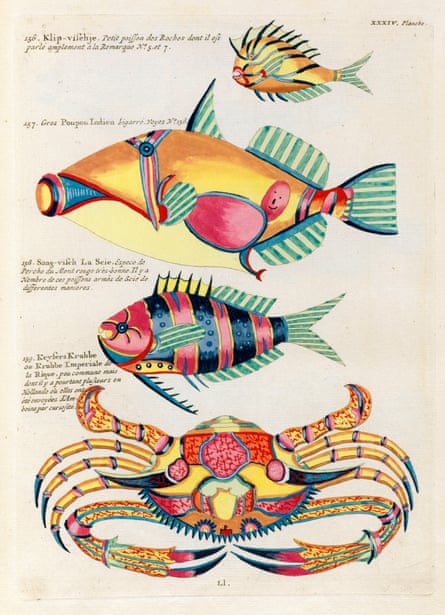

Poissons, ecrevisses et crabs by Louis Renard (1719)

In the 18th century, Europeans knew very little of Indonesian wildlife. Renard knew even less, but that didn’t stop this Dutch bookseller from confidently producing this vibrant two-volume collection. Thirty years in the making, the 100 plates carry 460 illustrations of marine biology. In the second volume, however, scientific accuracy swiftly becomes a casualty of artistic licence. Many of the fish have distinctly avian and even human features, as well as decorations of sun, moon, star and even top-hat motifs. Highlights include the spiny lobster, Panulirus ornatus, reported to favour a mountain habitat and possessing a penchant for climbing trees and laying red-spotted eggs “as large as those of a pigeon”. The Crabbe-Criarde, we are told, mews like a cat. Or the four-legged fish, the Loop-visch or Poisson courant (Running Fish) of Ambon, of which the writer notes: “I trapped it on the beach and kept it alive for three days in my house, where it followed me around like a very friendly little dog.”

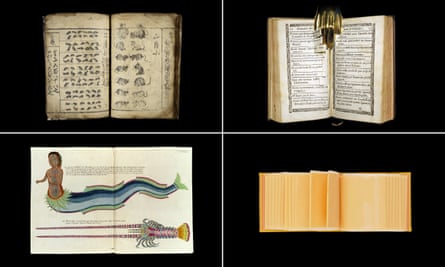

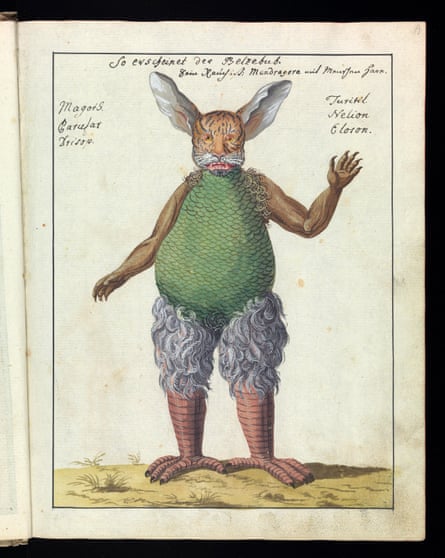

Compendium of Demonology and Magic, author and date unknown

While the date of 1057 is given on the title page (as well as the warning “Noli me tangere” – “Don’t touch me”), this is clearly in the tradition of presenting grimoires to seem much older than they actually are, and it is usually dated to 1775. With the witch-hunting hysteria having subsided by this time, you can see the artist relishing the freedom to exercise (or perhaps exorcise) his imagination. Over 35 extraordinary illustrated pages, the author paints conjurations, devils devouring limbs, flames and snakes bursting from crotches. One image shows a magician digging for treasure, only to find that his accomplice has been seized by a nine-foot cockerel-headed demon that is also casually urinating on their lantern. A pretty unambiguous warning against the “fashionable crime” of magic-based treasure-hunting that would remain popular across Europe for some time.

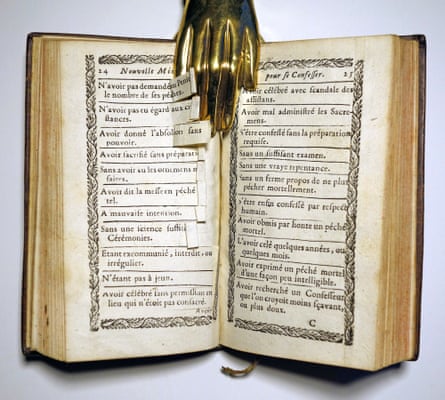

La Confession Coupée ... ou la méthode facile pour se preparer aux confessions by Christophe Leuterbreuver (1677)

Translated as “The Cut-out Confession; or the easy method of preparing for confession”, this book by a French cleric first appeared in 1677, and was so popular that it was reprinted in further editions as late as 1751. The book is a godsend to the forgetful sinner (and perhaps also the virtuous confessor in need of some sinful conversation material), as it comprises an enormous catalogue of every 17th-century sin conceivable, divided into chapters headed by the 10 commandments. Each misdeed is printed on a tab that can be peeled away from the page to stand out, helping the confessor to flick quickly through the book to find the relevant wrongdoings in the confessional.

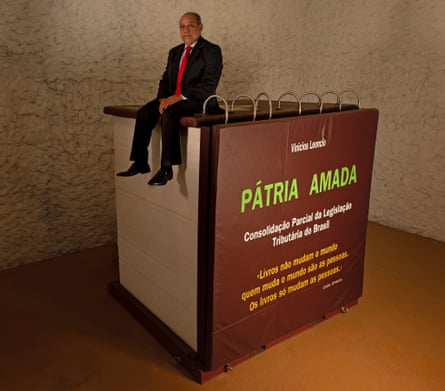

Pátria Amada by Vinicius Leôncio (2014)

In Brazil in 2014, a tax lawyer named Vinicius Leôncio created one of the world’s largest books as a form of protest. The result of 23 years’ work, Pátria Amada (Beloved Country), is a 7.5-ton testament to the ridiculous immensity and complexity of Brazilian tax laws. Leôncio was the first to bring together every Brazilian tax code in one volume (complete for only a brief moment, as 35 new tax laws are added to Brazilian legislation each day). Its 41,000 pages mean that the book is 2.10 metres thick, towering over any prospective reader. Leôncio spent R$1 million (£205,000) of his own money to print the book in a shed, using an imported Chinese printer accustomed to cranking out billboard posters. He spent an average of five hours a day researching and collecting the laws, with a staff that grew to 37. Three heart attacks, a divorce and a new marriage failed to dissuade him from his task of highlighting “the surreal, punishing experience” of dealing with a tax system gone haywire. “I simply thought that something should be done about the humiliation we must endure to pay our taxes in this country,” he said.

Though he was delighted to hear the story of his book would be included in my book, and kindly provided me with the accompanying photograph, Sr Leôncio is very happy to have left the project behind. He has no plans to publish a second edition.

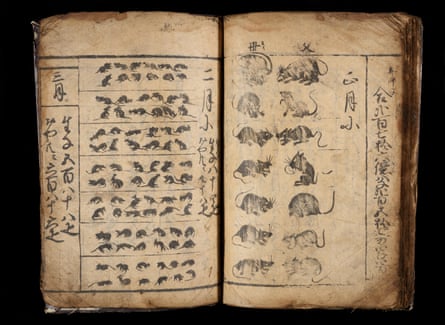

A Manual of Mathematics (Jinko ̄ki), author unknown, early 17th century

This is an extraordinary book. Instead of using line diagrams, the author uses drawings of rats in various poses to illustrate lessons in complex geometric progression and the calculation of the volume of 3D figures.

20 Slices of American Cheese by Ben Denzer (2018)

Only 10 copies were made of 20 Slices of American Cheese by Denzer, a New York publisher, which contains precisely what its title describes. A packet of 24 slices of Kraft American cheese slices costs roughly $3.50 (£2.70); 20 Slices sold for $200. I asked Emily Ann Buckler at the University of Michigan Library about the condition of its copy. “It’s apparently ‘shelf stable’,” she assured me, “but ... we’ll see how long it lasts.”

This is an edited extract from The Madman’s Library by Edward Brooke-Hitching, published by Simon & Schuster.