Cézanne’s Hard Truths

For Cézanne, stone represented structure incarnate.

If nothing else, the COVID-19 crisis has encouraged introspection. In my case, it’s been a chance to wander and weed through a library of several thousand volumes accumulated over half a century. As I was doing some routine fact-checking for this review, I opened a book on Cézanne and something fell out by surprise. What? Nothing less than my textual version of Proust’s madeleine!

The brochure came from an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art 43 years ago, Cézanne: The Late Work. That I’d kept the slender but double-sided, remarkably informative quarto sheet of paper so long got me thinking. William Rubin’s show still ranks among my all-time “top 10” list. If memory serves, I saw it more than any other exhibition – 30 or so visits over three months. It turned a postgraduate student from Britain on a study year in the States more fanatical about Cézanne than Abstract Expressionism.

So Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings tempts me to follow an example set by Robert Rosenblum. He once titled an Artforum article “Rothko and Me” – just before, as it happens, I myself reached the point when I could have spun a comparable tale. Indeed I loved Cézanne’s work well before I knew Rothko’s. If what I’m writing here seems personal enough to sound a bit like “Cézanne and Me,” it’s because I find it tricky to separate the Master of Aix from my own art historical apprenticeship and evolution.

On the evidence of the publication, Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings, which London’s Royal Academy canceled due to the pandemic, would have counted among the most interesting shows of its type — a “focus” neither too narrow nor too blurry. As it stands, the book is a serious contribution to the literature. John Elderfield’s lengthy essay — thorough, highly considered, and nuanced – makes one realize that the leitmotif of stone runs so deep in Cézanne’s vision that the wonder is no museum has already explored the subject. Perhaps curators could not see the rocks, so to speak, for the landscapes.

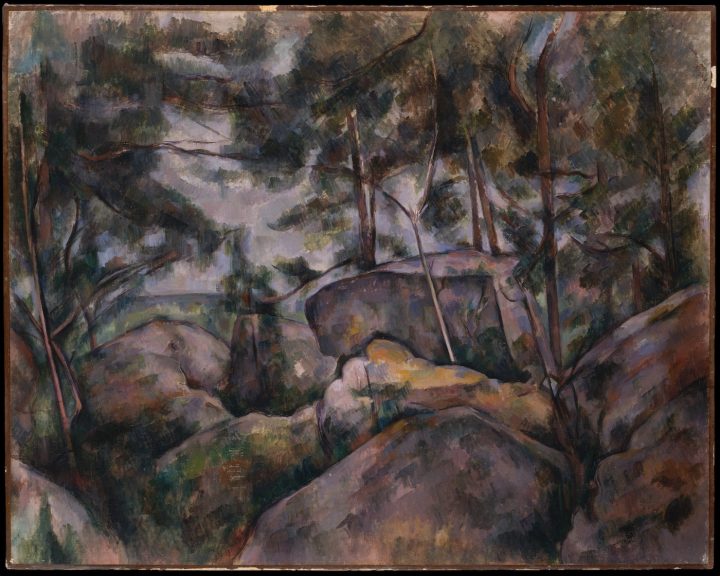

Then again, Cézanne’s landscapes at their finest are in effect still lifes redone from nature – given their monumental fixity, natures mortes in both senses of the term. Here lies one among several reasons why he battened upon stone. It represented structure incarnate. Faya Causey’s essay explores how Cézanne became engrossed with geology at an early age while studying at the Collège Bourbon in his hometown and pays special attention to a friend in his Aixois student cercle, Antoine-Fortuné Marion. The latter became a major scientist and doubtless stimulated Cézanne’s fascination with geology from the start. In the rocky strata of Provence’s geography and the huge boulders deep in the forest of Fontainebleau, the painter discovered key concerns.

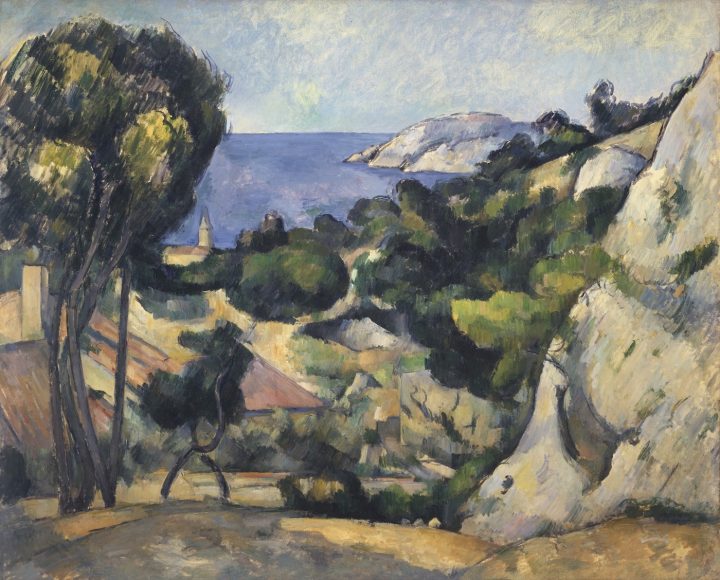

The first was nature’s inherent order as manifest by the layers, geometric patterns, and other striking shapes that the earth assumes. Already in the paintings from the first half of the 1880s, which treated the coast between the seaside village of L’Estaque and Marseille, the vistas and their depiction project a strange, rhyming synergy. Put another way, the serried, repeated rhythms made by the Kimmeridgian limestone fuse with Cézanne’s facture. Mimesis of a special kind is at stake, leading paradoxically toward the abstract. “Rocks at L’Estaque” (1883) and “At the Bottom of the Ravine” (c.1882) exemplify this perceptual equation. One might say that the “cubes” of Cubism lay dormant in the mineral slabs of the Midi’s maritime scenery.

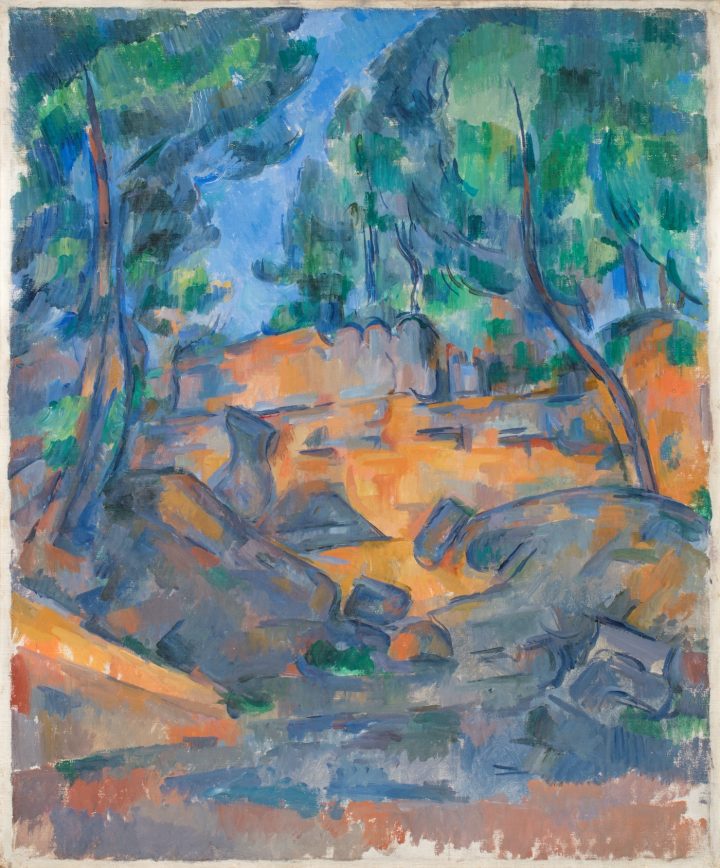

Again I find a serendipitous personal link. In short, at school I wanted to be a chemist, not an art historian. In hindsight, the urge had nothing to do with science per se and everything to do with the colors and geometries of crystal substances — sulphur, potassium permanganate, iodine, copper sulphate, and so on, as I melted the chemicals over a Bunsen burner or dissolved them in water. It must have been this fascination that lay at the root of my childhood attraction to Cézanne’s crystalline facets, which climax in canvases such as “Montagne Sainte-Victoire Seen from Bibémus” and “The Red Rock” (both 1895-1900). There, an odd metamorphosis occurs. Erstwhile swaying trees and vegetation change into lapidary structures, whereas cliff, mountain and ravine grow animate.

Crudely stated, the obvious conclusion — mindful of diverse biographical facts — is that Cézanne’s problems with fellow humans drove him to a rapport with nature that borders on the obsessive. My romance with chemistry subsequently segued into another with… rocks and minerals. (No, I’m not a New Age leftover who imagines these objects to have healing cosmic powers and similar nonsense). It’s the remarkably intricate structures, sometimes resembling the organic, alongside the myriad colors and luminosity that enthrall. In the same breath, I’m aware that like many a collector — whether of stamps, wine, plants or paintings – an obsessive-compulsive impulse runs somewhere beneath the surface of these everyday passions.

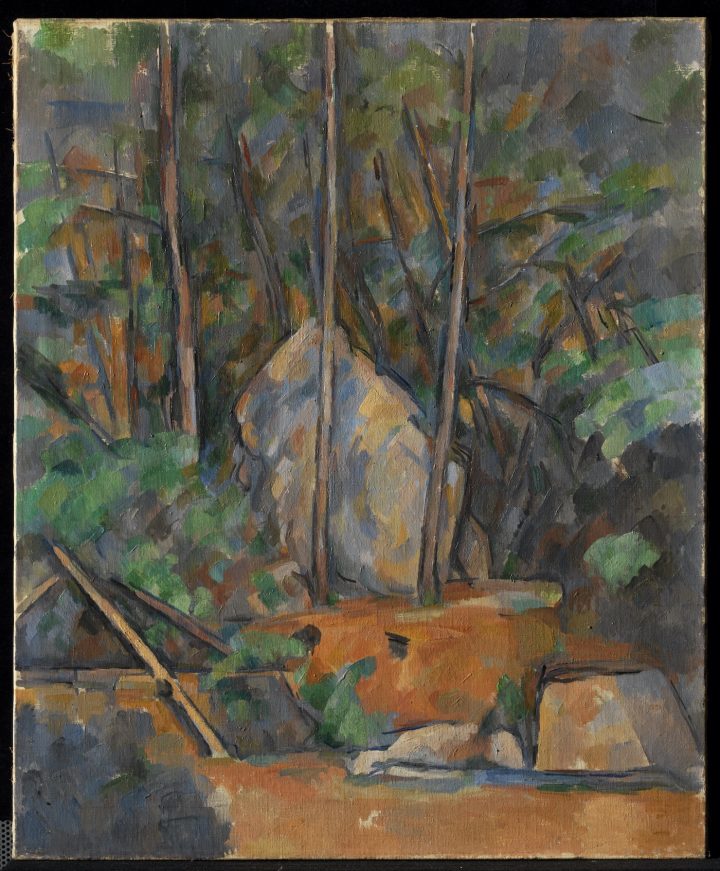

Obsessive-compulsive types are famously given to repetition. The Austrian composer Anton Bruckner — prone to count bricks in buildings and many other similar fetishes — is a quintessential example of this behavioral syndrome. Flash back to MoMA’s Cézanne: The Late Work. Surveying entire walls filled with oils or watercolors depicting skulls, craggy forest depths, the Fontainebleau blockfield, and Mont Sainte-Victoire, the compulsion to repeat became as clear as it was infectious. Cézanne’s oft-quoted remark about being pleased with Ambroise Vollard’s white shirt-front alone after 140 portrait sittings encapsulates the same traits. The “constructive” brushstrokes rising to a tactile crescendo in the Chateau Noir and Bibémus compositions evoke the obsessive-compulsive temperament disciplined into compositional rigor.

The current catalogue brings to the fore the sheer mystery and strangeness of Cézanne’s entire creative project. His rage for order countermanded an unstable wildness that at its most extreme courted psychopathology. Elderfield notes the numerous weird aspects — the early anthropomorphic landscapes, the corporeality of the watercolor washes that outline the rock faces, and the especially strange “In the Bibémus Quarry” (1900-04), where a tiny faceless figure sits embedded within a V-shaped crevice that one scholar has compared to a vagina. Nevertheless, Elderfield ultimately tends to come down on the side of reason, formality, and empiricism. I’m not so sure.

Certainly, to read Cézanne’s artistic processes and imagery as the fever chart of a disordered mind is crass. Period. In the same breath, Meyer Schapiro’s approach established the disruptive forces that the painter distilled into his mature still lifes. He also discovered in Gustave Flaubert a very convincing subtext to Cézanne’s tumultuous “stonescapes.”

In L’Education Sentimentale (1869), Flaubert wrote about two lovers for whom:

[…] the rocks filled the entire landscape […] like the unrecognizable and monstrous ruins of some vanished city. But the fury of their chaos makes one think rather of volcanoes, deluges and great forgotten cataclysms. Frédéric said that they were there since the beginning of the world and would be there until the end. Rosanette looked away, saying that it would make her mad.

At the core of this exhibition, its publication, and its scholarship stand two interpretative trends that, though not mutually exclusive, point in opposite directions. Do we, as it were, identify with Flaubert’s Frédéric or rather Rosanette?

Elderfield tends to the former, associating Cézanne’s standpoint with burgeoning trends in the era’s geological and other empirical sciences. In that case, it would have further strengthened his thesis to have cited an American context. Namely, the role science played in Frederick Edwin Church’s work. Much influenced by the German polymath explorer Alexander von Humboldt, Church pictured nature as a vast harmony, a great whole animated by the breath of life.

By contrast, an obsessive-compulsive mindset involves the feeling that inanimate objects are ensouled, inclines toward the omnipotence of thoughts, and fixates on order, symmetry, and repetition. According to Madame Cézanne, her husband used to say, “the landscape thinks itself in me, and I am its consciousness.” In his work, the habitual alignment between one contour and another, and the multitudinous pigment marks — Cézanne’s celebrated taches — resemble obsessive-compulsive behavior, in which tasks are repeatedly performed as if they were not properly done the first time. In Cézanne’s hands, the outcomes of such an attitude were of two extremes: surfaces layered into crusty impasto, or else left non finito, in which large expanses of primed canvas or bare paper prevailed.

Or maybe Cézanne more aptly bears witness to the old cliché claiming that a thin line separates the madman and the genius? Romanticism pitched to a certain degree will turn into classicism. The homeboy, so intoxicated by terroir, is here changed into a geomancer wielding a brush instead of a divining rod. (By no coincidence, a notable wine domaine in the southern Rhône is called “Le Sang des Cailloux,” the heady “blood of the stones”).

While an undergraduate at the Courtauld in the 1970s, I almost got that “madman or genius” feeling when in proximity to the uncontested Cézanne-meister there, Robert Ratcliffe. A scholar as profound as he is now obscure — his lectures were protracted marvels laden with the minutest attention to details, perspectives, angles, maps, painstaking photographs that he had taken of actual sites à la John Rewald gone manic — Ratcliffe had the slightly unnerving quality of someone driven into the most acute objectivity by some deep, unconscious turmoil. Pure reaction formation, a defense mechanism against nameless anxieties.

One last element adds a personal coda to Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings. The truest heir to Cézanne’s stone-saturated pictorial universe was a figure long dear to me. I wrote my PhD thesis largely on his art and thought (the other main subject being Rothko), and in fact, he had written his MA in 1935 on Cézanne. Deeply preoccupied with stone and the earth in its many guises — structural, ominously Romantic, animistic, and much else — the visionary in question is Clyfford Still.

As a young artist in the 1920s, Clyff twice depicted a cliff, a homonym of his name and an apt rebus for his towering, formidable self. As Cézanne was an outsider long misunderstood, so too has been Still, who forged a form of abstraction as dense, disciplined, and intense as his forbear’s rock and quarry images.

Ages ago on a European road trip, I got out of a rental car that we’d parked on the roof of a supermarket in Aix-en-Provence. Turning round to head into the store, the sudden sight that loomed afar was the perfect view of Mont Sainte-Victoire’s timeless profile, from a spot where Cézanne could never have stood. I immediately thought of the delight with which Still, with his mordant wit, taste for road trips, and uncanny eye for correspondences across time, nature, and the self, would have appreciated the irony of that decisive moment.

Cézanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings (2020), edited by John Elderfield, with contributions by Ariel Kline, Faya Causey, and Sara Green, is published by Princeton University Art Museum.