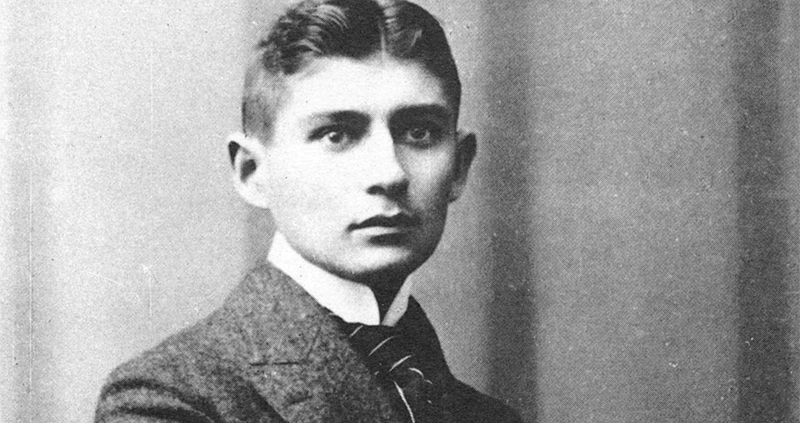

On Reengaging with Franz Kafka’s Astonishing Worlds

Gregory Ariail Considers the "Lost" and Newly Translated Fragments

Unofficial and incomplete texts are nothing new to readers of Franz Kafka; the problems of textual authority haunt nearly all his work. Kafka’s aesthetic practice cultivates a resistance to finality and what Judith Butler calls a “poetics of non-arrival.” The bulk of the literary output he left to posterity, as Michael Hofmann notes, “ends” rather than “finishes.” More crucially, all of Kafka’s novels, and a considerable haul of his short stories, beast fables, and aphorisms, owe their existence to Max Brod’s refusal to honor his best friend’s wish and burn all the manuscripts in his possession (unlike Kafka’s last lover Dora Dymant, who destroyed those in her keeping). The material in The Lost Writings is no more fringe or “lost” than any other unfinished text like The Castle, The Trial, Amerika, “The Great Wall of China,” “Investigations of a Dog,” or “The Burrow,” since Kafka’s publication history has been determined by the accidents of editorial preferences and decisions over the last century.

Regardless, Kafka, along with his editorial and translational collaborators, is one of our most prolific contemporary writers. Countless new editions, from retranslations of his novels and short stories to fresh arrangements of his aphorisms and a collection of his office writings have appeared in English in the last ten or so years. And now, with Franz Kafka: The Lost Writings, out from New Directions on October 6, Kafka strikes again—with a book that begs some important questions.

The billing of this release, whose texts were chosen by the Kafka biographer Reiner Stach and translated by Michael Hofmann, doesn’t completely reflect writings that are “lost”—a number of these fragments, such as “A Report to An Academy: Two Fragments” and “Prometheus,” are long-established pieces that can be found in The Complete Stories, and others have been published before in The Blue Octavo Notebooks and Stach’s Is that Kafka? 99 Finds. There are, however, hitherto untranslated “finds” that will make a Kafka lover’s heart flutter. Like certain minerals, they cleave at near-perfect angles and conclude at an appropriate place where the well of Kafka’s inspiration ran dry or at a climactic moment; they leave the reader anxious for more and spur one to imagine dark and strange narrative possibilities that will never be realized. Here we have intriguing false starts and alternative versions of visionary flash fiction pieces like “The Bridge” and “Jackals and Arabs.”

From Stach’s selection of 75 fragments, I’ve distilled a few plots and premises from the fables and fairy tales that most took my breath away: a creature with a vulpine tail trains the human narrator rather than vice versa; a thin, lascivious man, with a face no bigger than the palm of a hand, has fused into a theater’s parapet; assistants with bushy, jerking squirrel tails scale the drawer-studded walls of a nightmare pharmacy; gravediggers the size of pinecones labor happily in a forest; a rainstorm only occurs indoors; a general falls from the heavens into a ditch; a prison cell is open to the air yet without exit, since it towers high above grey mist; a ragtag group of soldiers defends a farm from an unknown and unseen enemy; a man takes up residence in a stable with his beloved horse, Eleanor, and harbors regrets about it; a coffin’s inhabitant suddenly knocks open the lid; and mouse parents mourn their daughter, flattened in a trap’s steel blade.

I tend to gravitate less towards Kafka’s paranoid bureaucratic and legalistic thought-mazes than to the fantastic and nonhuman elements in his work. I’m shaken to the core by his weird little tales reminiscent of Hasidic legends, Zen koans, and beast fables. From time to time I crave their mysticism; their weird assemblages; their dusty attics; their sudden unravelings and epiphanic violence. Kafka’s fables about creatures and hybrids trouble the boundaries between subject and object, organism and thing, and expose the arbitrariness of concepts of hierarchy, dominion, and mastery. As Jane Bennet writes, they “avow the force of questions rather than answers” and embrace “discredited philosophies of nature.”

The Kafka industry treats this Czech-Bohemian Jew writing in German as a secular Baal Shem Tov, or like other mystics and prophets, one for whom it’s imperative to publish every scrap of language, whether biographical and apocryphal or fictional. Gustav Janouch records Kafka’s mind-bending conversations while Brod claims that his friend, despite his vexed relationship to Judaism, was a “sacred” writer “on the road to becoming” a “saint.” Almost every crumb of fictional narrative has been extracted from Kafka’s diaries and notebooks and served up as worthy of notice; for aficionados, each aphoristic sentence has the potential to spark a small revelation. Kafka’s cult of personality generates a fiercer following than many other modernist writers because of his romantic and artistic demons, but also because of the tantalizing slimness of his official literary output.

I try to resist the hagiographic impulse to cast Kafka as a saint of literature whose sublime works showcase his uncanny imaginative strength and claim to cultural permanence, or some such figuration of the canonical author. Rather, when I reengage with Kafka’s astonishing worlds, I consider: What other narratives am I neglecting? What am I cutting out of the list of my life’s reading? Inevitably something won’t get read that would have been if I wasn’t reading Kafka for the umpteenth time—maybe during the time I spent with these “new” fragments I sacrificed the hours I would’ve otherwise devoted to a contemporary text, say Hiroko Oyamada’s The Hole, N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, or Jeff VanderMeer’s Dead Astronauts.

It’s true that the dead writers we love, with that fierce love that only someone that changes the complexion of our inner lives can create, can both nourish and rob us of experience.By consuming every line of a canonical writer, by scraping every inch of material from his corpus, we certainly can gain something, but we can lose something, too: perhaps a vital encounter with a present-day consciousness. Certainly, we should cut a broad temporal swath in our reading, mix old and new writing to gain important cultural-historical perspectives, but it’s true that the dead writers we love, with that fierce love that only someone that changes the complexion of our inner lives can create, can both nourish and rob us of experience.

There are countless other weird fragments I would have included in The Lost Writings, gathered from Kafka’s notebooks and diaries: an old man with wings who refuses to leave his hometown during a siege; a dog so faithful she rots against her owner; a demon, tinier than the tiniest mouse, that lives in the corner of an abandoned cabin in the woods; a white wall that is actually a giant’s forehead; an ancient knight’s sword buried to the hilt in the narrator’s back without causing him any pain. Maybe as a parting gesture to my heart’s writer (Kafka’s “The Burrow” changed my entire outlook towards literature), I’ll create a handmade book of my most beloved Kafka fragments. I’ll translate them clumsily and give them to a friend to read if she’s bored. This is the moment to sail into new waters, but whether I’ll be going forward, backwards, or nowhere, only time will tell.

Gregory Ariail

Gregory Ariail is a Prison Arts and Education Project Fellow at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa. His writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, The Journal, The Common, Indiana Review, CutBank, and others. He recently completed his Ph.D. dissertation on the Anglo-American imitators of Franz Kafka's fables and has scholarly work forthcoming on the subject.