-

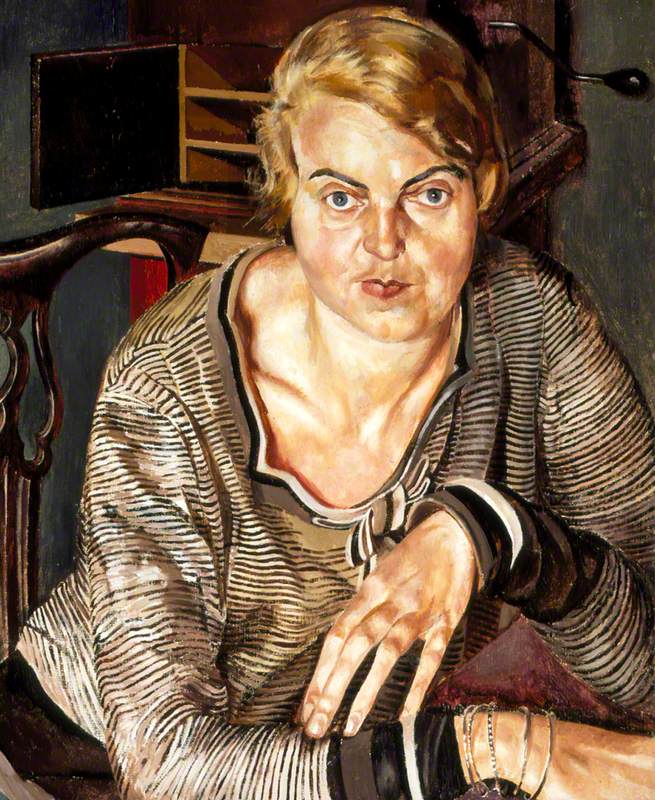

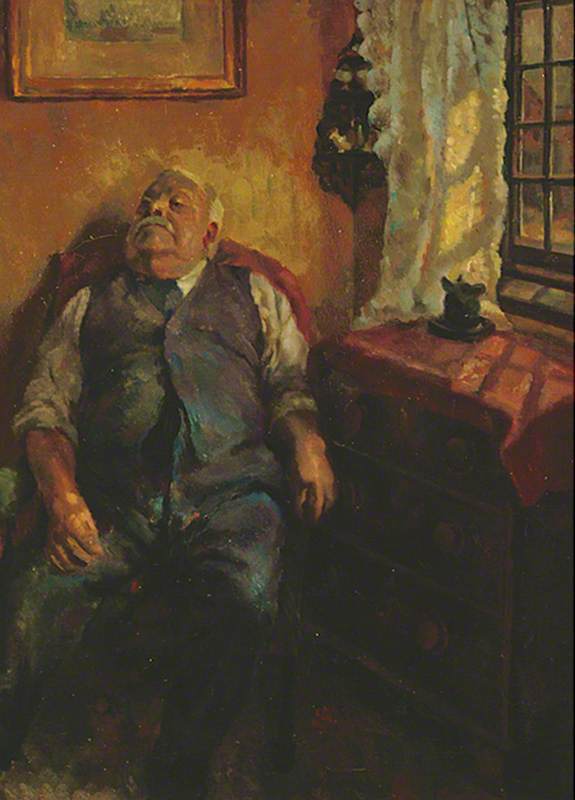

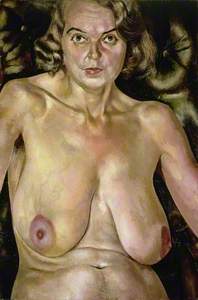

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Newport Museum and Art Gallery

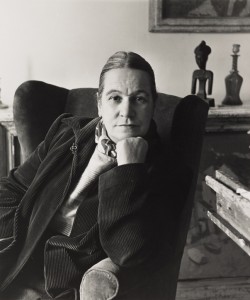

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

Newport Museum and Art Gallery -

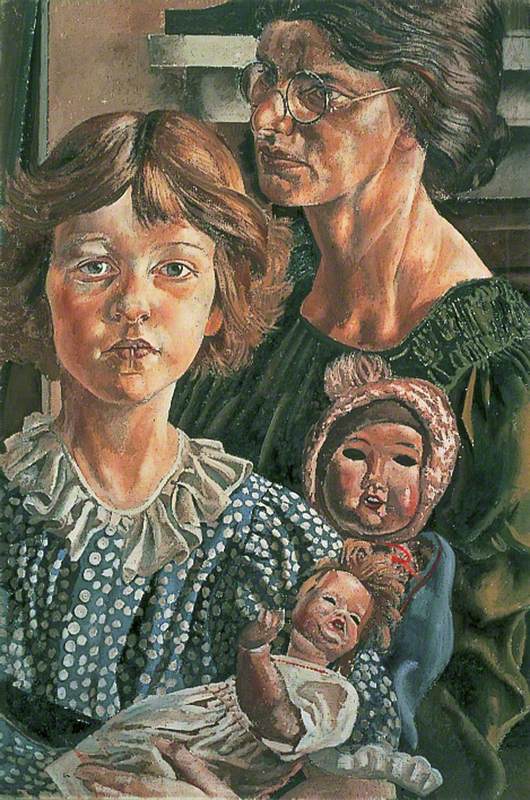

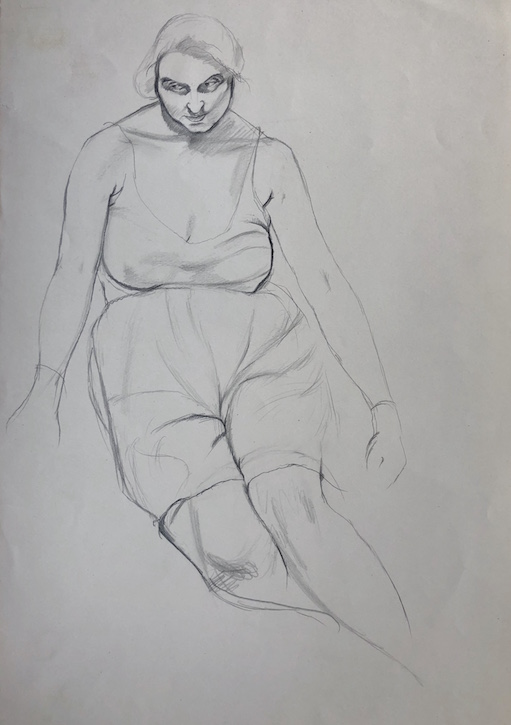

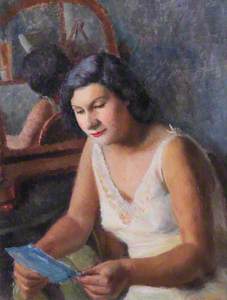

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: The Box (Plymouth City Council)

Cottage Interior with a Seated Man

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

The Box (Plymouth Museums Galleries Archives) -

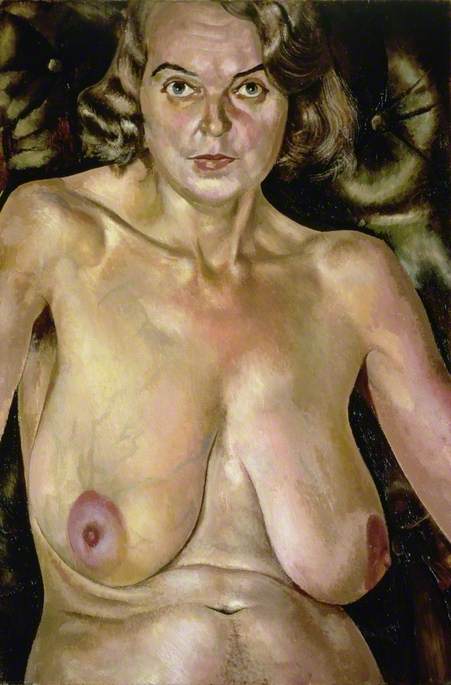

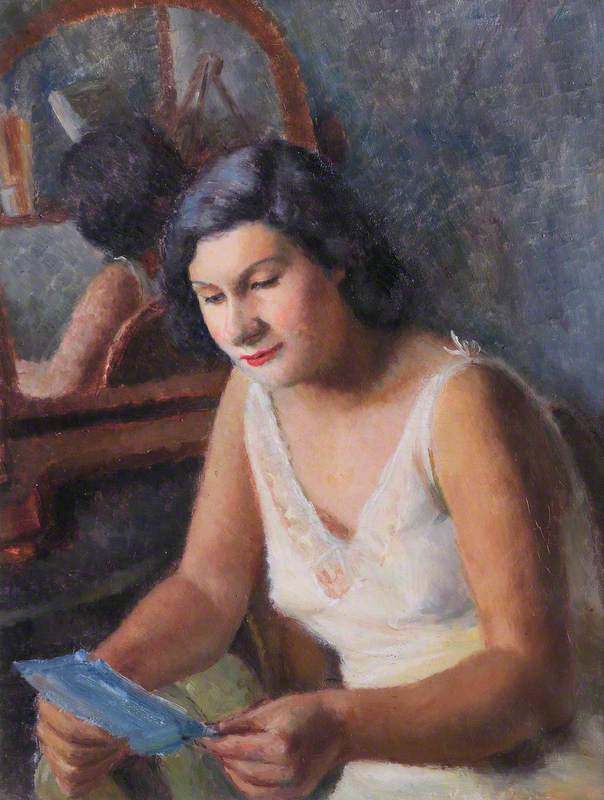

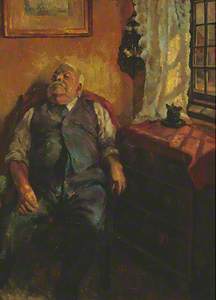

Photo credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece represent an important – if morally ambiguous – LGBTQ+ story in art history. It's difficult to consider the couple without also thinking about Stanley Spencer, the legal husband of Preece and an artist who has been more thoroughly researched than his artist wives, lovers and children.

Trying to trace the outlines of their lives around Spencer might imply he held the dominant position in the relationships. However, while Spencer certainly overshadowed his first wife Hilda Carline's artistic output (she rarely painted whilst married to him), his relationship with Patricia Preece was different. Preece, with her partner Hepworth, pushed back and took. Whether their actions were 'right or wrong', their story is of two women looking out for one another and deceiving the art world, together, for their entire lives.

© the copyright holder. photo credit: The Court Gallery

Patricia Preece

1928, pencil on paper by Dorothy Hepworth (1898–1978)

Of Dorothy Hepworth and Patricia Preece, more is known about Preece. Even as a young teenager, her life contained dramatic events involving men, with a hint of sex and scandal. In 1911, Preece went for a swimming lesson with W. S. Gilbert (of Gilbert and Sullivan). While swimming in the lake at Grim's Dyke, an estate owned by the dramatist, Preece lost her footing and called for help. The elderly man swam in to help her and died of heart failure caused by exertion. Preece was described in the inquiry as a 'fair-haired seventeen-year-old schoolgirl'. Ruby Vivian Preece, as she was known, then became Patricia.

As a young adult, Preece attended the Slade School of Art in London where she met Dorothy Hepworth. The two became close, though they had quite different personalities: while Preece was outgoing and flirtatious, fashionable, and only got a pass at the art college, Hepworth was quiet and reserved, wore subdued clothing and took first-class honours. The women set up a studio/home together, with financial help from Hepworth's wealthy father. It was at this point that Preece began to receive praise for her art from other artists – Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell – though, as we will come to later, she was hiding a strange secret.

For a short period, the two women went to study art in Paris with the Cubist painter André Lhote. It was here that they attended the salon of the influential American Natalie Barney, who promoted women's writing and lived openly as a lesbian. While Preece and Hepworth were dedicated to each other, it is said they were not so open about their sexual relationship, instead sometimes claiming to be sisters, with Preece referring to herself as 'née Hepworth'.

The two women later returned to Britain's west country, then in 1927 settled in the village of Cookham, where Hepworth's father purchased them a house. Yet within a few years, their benefactor lost his money in the stock market crash, and had died, leaving the pair without an income to pay the mortgage.

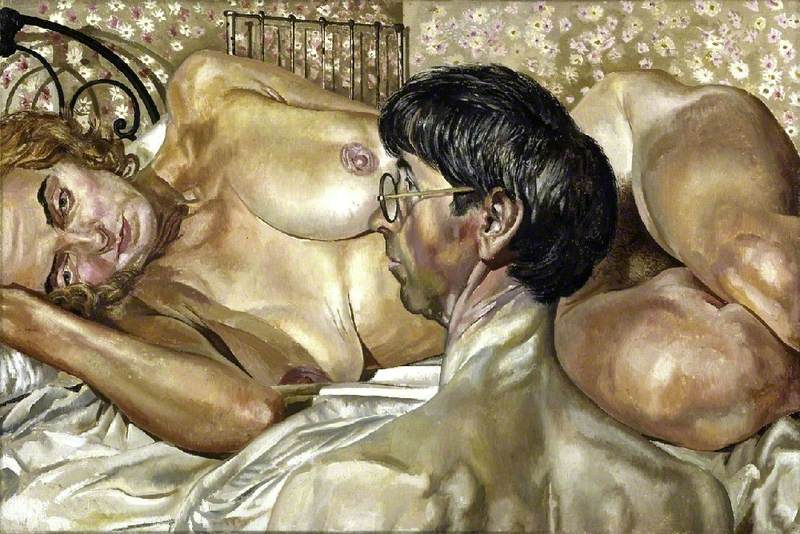

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary ArtIt was in Cookham that the pair met Stanley Spencer and his wife Hilda Carline: Preece while working as a waitress in a tea shop in Cookham. The women went to their artistic social events and helped with the children. The family moved into the house next door to Preece and Hepworth in 1932.

Stanley Spencer became very close with Preece, having her sit for paintings, travel with him as a translator when away for commissions, and inviting her and Hepworth to move into his family home (which they refused). Times were financially fraught for the two, so it is interesting that they chose not to take up this offer.

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: City & County of Swansea: Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Collection

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

Glynn Vivian Art GalleryThe bold, striking Preece had a hold over Stanley Spencer, who reputedly used her sexuality to manipulate him, accepting expensive gifts and appearing semi-dressed in his company. This was to the devastation of Spencer's wife, who moved away to Hampstead, housing one of her daughters with a relative.

The family split apart, Spencer dreamt of reuniting with his wife, together with Preece in a ménage à trois. He wrote to Carline, in 1936:

'There is something between you and me which must not be broken. The law does not allow me to have two wives. Yet I must and will have two. My development (as an artist) depends on my having both you and Patricia.'

Carline was not happy with Spencer's proposal. In a turn of events, which perhaps has since overshadowed most artistic achievements of Carline, Preece or Hepworth (notably not Spencer himself), Stanley pressurised Hilda into a divorce in 1937, marrying Patricia Preece less than a week later – and Preece took her partner Dorothy Hepworth on the St Ives honeymoon while Spencer stayed home to work on a painting.

It is speculated that the events that followed were plotted by Preece herself: she wrote to Carline, inviting her to pick up any things from the house and then come along with Spencer to join their honeymoon. After Spencer and Carline then spent the night together, Preece refused to let her new husband touch her.

Spencer's portraits of Preece at this time show a kind of euphoric ugliness. Did he deliberately generate this kind of awkward discomfort and misery in his home life to inspire his art? He saw his love for both Carline and Preece as sacramental: 'Desire is the essence of all that is holy', he said. In his famously frank Self Portrait with Patricia Preece, he kneels before her, like an altar, the flesh tones so lurid as to look almost cadaverous.

Preece and Hepworth continued to live together after the wedding, and after Preece gained control of Spencer's finances they evicted him from his house in 1938 to rent it out. Within two years, Spencer was penniless and living in a bedsit in Swiss Cottage in London.

Meanwhile, what did Dorothy Hepworth think of all this? Was she as complicit in the manipulation of Spencer as Preece herself? Did she also see a reflection, in part, of her own relationship with Preece?

In a deception that has confused galleries and curators up until this day, Dorothy Hepworth allowed her art to be signed by Patricia Preece. Incredibly shy, Hepworth allowed the outgoing Preece to exhibit work under her name, in upmarket London galleries. Preece was praised by Duncan Grant, the work bought by Augustus John and Virginia Woolf. Yet the latter wrote that Preece was visibly flustered at the prospect of having to paint a portrait commission (which she later got out of doing), and Stanley Spencer said he'd never seen her with a paintbrush in her hand.

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Bangor University

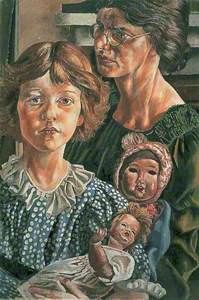

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

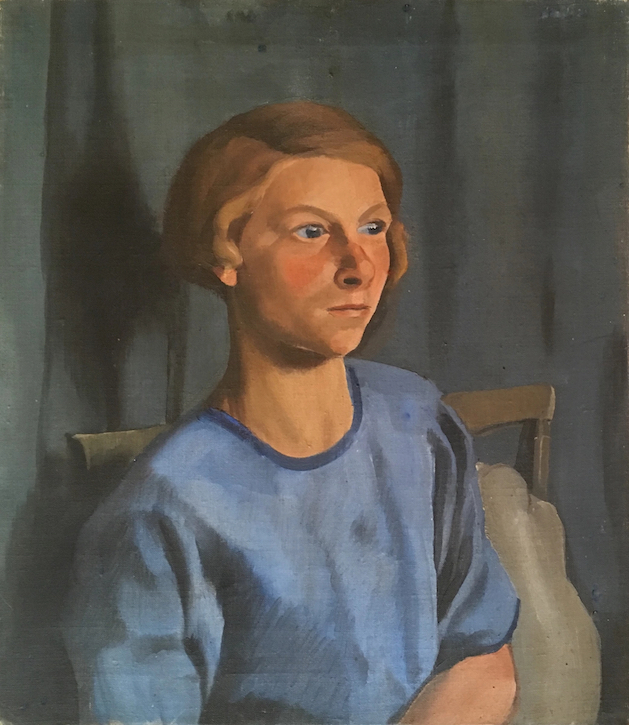

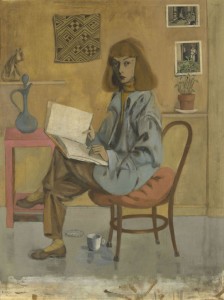

Bangor UniversityClive Bell noted, in the foreword to an exhibition of works 'by Patricia Preece', '[s]he is Nordic rather than Latin, psychological rather than decorative. Certainly in her own way she is a psychologist, and not less certainly – this is what matters – she is a painter.' Slightly reminiscent of the work of Gwen John, Hepworth's skill was in picturing quiet figures at rest, with warm muted tones in elegant simplicity. The power of the paintings comes from their stillness.

© the copyright holder. photo credit: The Court Gallery

Girl in Blue, Cookham

1927, oil on canvas by Dorothy Hepworth (1898–1978)

Photo credit: The Court Gallery

Dorothy Hepworth with 'Girl in Blue, Cookham'

c.1928, photograph

It is hard to imagine Dorothy Hepworth's internal monologue. From today's perspective the partnership could seem ahead of its time: the work 'produced' by the pair, working in unison as maker and promoter – the talent needs the face, and the face needs the talent. Michael Dickens, researcher of Hepworth's work, found one reference in a 1959 newspaper in which Preece announces she will allow Hepworth to use her name 'to promote her painting'. He also found, in diary entries, Preece admitting she had very little do with the actual creation of the works, besides arranging objects for Hepworth to paint.

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

Wolverhampton Arts and HeritagePreece seems to have been a taker and, in a perverse way, a giver too: with Hepworth, she encouraged and promoted but took the admiration. With Spencer, she gave him an almost 'divine' inspiration, with her flesh, sexuality and spirit, but took... well, everything. Preece never granted Spencer a divorce, and after he was knighted in 1959, and died in the same year, she insisted on being called 'Lady Spencer', claiming his pension. Why did she treat him so badly? Preece said of Spencer's work, 'I very much dislike it... He had to turn me into something horrible to obtain maximum satisfaction from our liaison. There was something appalling about Stanley'.

With Dorothy Hepworth, however, the pair remained together until they were old, with Preece dying in 1966. Hepworth lived until 1978, being cared for occasionally by Preece's sister: it has been said that Hepworth, in her later years, was 'an austere, shadowy figure surrounded by the village types, grizzled codgers and scullery maids, whom she catches so vividly in her drawings'. The fact that after Patricia's death Dorothy still continued to paint – and to sign her work 'Preece' – hints their relationship was symbiotic rather than parasitic: they worked together, using their individual strengths to create a public life together.

The pair's remains are buried together, in Cookham Parish Cemetery, under a stone which reads:

VIVIAN SPENCER

1894–1966

A DEAR FRIEND OF

DOROTHY HEPWORTH

8 SEPTEMBER 1978

UNITED IN LIFE AND IN DEATH

Hilda Carline's remains are also buried there, while Stanley Spencer's are at Holy Trinity Church, a 30-minute walk away through the village.

Jade King, Head of Editorial at Art UK

More on this subject is addressed in the exhibition 'Love, Art, Loss: The Wives of Stanley Spencer' at the Stanley Spencer Gallery, in Cookham.

At the time of publishing, works on Art UK are listed as by 'Patricia Preece (1894–1966)' (not Dorothy Hepworth, 1898–1978). A consultation with the artworks' owning collections is underway with regards to how best attribute the works and to represent the nature of the women's collaboration.

More stories

-

-

Fetching Shoes. 1939–1943, pencil on paper, 40.6 x 28 cm by Stanley Spencer (1891–1959). Private collection. © The Estate of Stanley Spencer. All Rights Reserved, 2017. photo credit: Private collection

-

Self Portrait. 1946, oil on masonite by Elaine de Kooning (1918–1989) . © courtesy Elaine de Kooning Trust. Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

-

The Lady Frances and the Lady Catharine Jones Daughters to the Right Honble Richard Earle of Ranelag. 1691, mezzotint by John Smith the mezzontinter (1652–1743) after Willem Wissing (1656–1687) and Jan van der Vaart (c.1653–1727). photo credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

-

-

Self Portrait. marble (?) by Anne Seymour Damer (1748–1828). Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Photo credit: Michalis Famelis, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

-

Study for 'Branded'. 1982, oil on paper, 100.3 x 74.4 cm by Jenny Saville (b.1970). Purchased (Henry and Sula Walton Fund), 2017. © Jenny Saville. photo credit: National Galleries of Scotland

-

Jane Austen. c.1810, pencil & watercolour by Cassandra Austen. Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

-

-

Palette. oil on wood palette by Rosa Bonheur (1822–1899). Photo credit: Minneapolis Institute of Art, Public Domain

-

-

-

-

Self Portrait. 1946, oil on masonite by Elaine de Kooning (1918–1989) . © courtesy Elaine de Kooning Trust. Photo credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

-

Still from 'Ammonite'. 2020, film by Francis Lee. Photo credit: NEON Rated, LLC. All rights reserved.

-

Anne Redpath, 1895–1965. Artist.. 1949, silver gelatine print photograph by Lida Moser. Photo credit: The Estate of Lida Moser / National Galleries of Scotland

-

Vera 'Jack' Holme (left) and Dorothy Johnstone (standing). 1918, photograph by unknown photographer. photo credit: LSE Library (source: Wikimedia Commons)

-

-

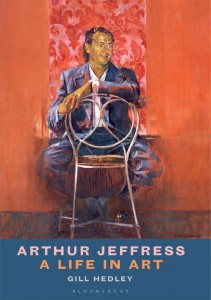

Cover of 'Arthur Jeffress: A Life in Art' by Gill Hedley

-

Jeune femme aux perles . unknown date, oil on canvas by Marie Laurencin (1883–1956). © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2020. Photo credit: Nahmad Projects

-

Ithell Colquhoun: Genius of The Fern Loved Gully. 2020, front cover of book by Amy Hale, published by Strange Attractor Press

-

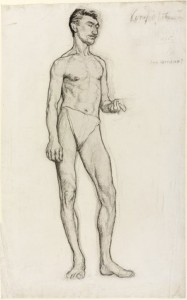

A Study of a Nude Male Figure. 1895, black chalk by Ida Margaret Nettleship (1877–1907). Photo credit: UCL Art Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Artworks

-

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Towner

Girl in Yellow DressPatricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Patricia Preece 1929Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

-

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: Southampton City Art Gallery

Patricia Preece 1933Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

-

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: City & County of Swansea: Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Collection

Interior with Figures 1935Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: Bridgeman Images

Family Group: H…Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

-

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: Bridgeman Images

Nude, Portrait…Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

-

© the estate of Stanley Spencer. All rights reserved, 2014 / Bridgeman Images. Photo credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum

Self Portrait with Patricia Preece 1937Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

-

© the copyright holder. Photo credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre

Old Woman Knitting 1…Patricia Preece (1894–1966)

-

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Bangor University

Girl Reading LetterPatricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage

The VisitorPatricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Towner

In a CottagePatricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

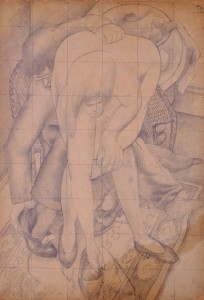

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: Newport Museum and Art Gallery

Girl KnittingPatricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

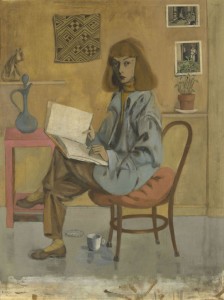

© the copyright holder & © the copyright holder. Photo credit: The Box (Plymouth City Council)

Cottage Interior wit…Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)

-

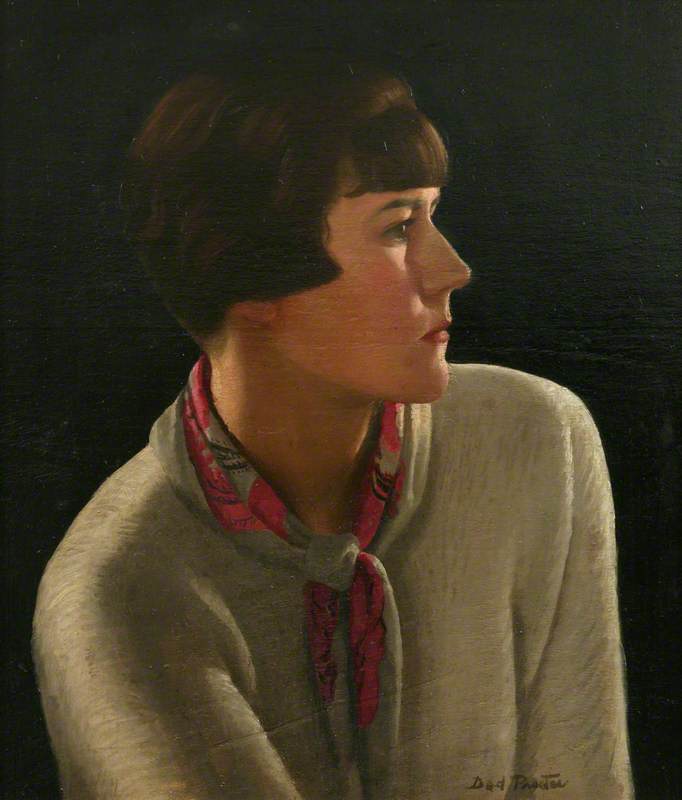

Photo credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Miss M. Steele 1942Patricia Preece (1894–1966) and Dorothy Hepworth (1894–1978)