Galois theory for non-mathematicians

How a teenager invented a new branch of mathematics to solve a long standing open question about equations

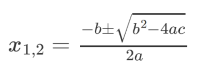

You might know that to solve an equation of degree 2, ax²+bx+c = 0, we use the quadratic formula.

There

exist similar formulas for equations of degree 3 and 4, but they are

mysteriously missing for 5 or higher. More specifically, it seems like

we cannot construct the solutions to the quintic (equation of degree 5)

or higher using only addition, subtraction, multiplication, division,

and radicals (square roots, cube roots, etc). Why is that, what’s so

special about the number 5? These were questions that haunted the young

Frenchman Evariste Galois

in the early 1800s, and the night before he was fatally wounded in a

duel, he wrote down a theory of a new mathematical object called a

“group” that solves the issue in a surprisingly elegant way.

This is how he did it.

TL;DR

The

set of roots of different equations are of different complexity. Some

sets are so complex that they cannot be expressed using only simple

objects such as radicals. But how do we measure the complexity of the

roots if we cannot even calculate them, and what measure of complexity

should we use?

Permuting roots and symmetry

The answer lies in the symmetry of the roots.

Symmetry of the roots you may ask, what does that have to do with anything? What does it even mean?

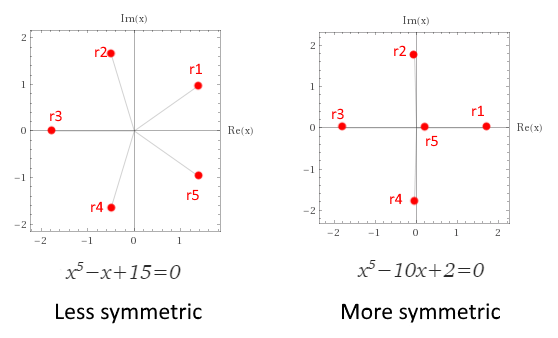

Let’s plot the roots of two equations and see if we can make sense of it:

The

left one is said to be less symmetric than the right one. This might

surprise you, because in the colloquial sense of the word, symmetric is

usually used if one can reflect or rotate the object without changing

the way it looks. In that sense, the left picture looks more symmetric.

For example: The star is more symmetric than the heart, because aside from reflecting it, one can also rotate it.

But

in our case, we are going to take a more general view of symmetries. We

are not restricting ourselves to only reflections and rotations, any

function that transforms the object without changing the way it looks is

fair game. In the case of the roots, that means that any function that

interchanges (permutes) the roots in any way is valid. More functions

means more symmetric.

It turns out that in the right case, there are functions for permuting all the roots in any conceivable order, as many as 5!=120, so it is highly symmetric. But in the left case, if we interchange r₂↔r₄ using the transformation i↔−i we necessarily also interchange r₁↔r₅. This restricts us, and thus all conceivable permutations are not possible. It is less symmetric.

The

functions that permute the roots are called “Automorphisms”, and if we

group those automorphisms together we get what is called a “Group” (I

will get back to better definitions of automorphisms and groups later

on).

This

means that the group that represents the symmetries of the roots is

larger and more complex in the right case. In fact, the group in the

right case is so complex that the roots cannot be described using

radicals.

How do we know how complex a group is? To understand this we need a bit more theory.

The size of the quintic

First, let’s take a look at the size of a group. How do I know that there are some quintics that have a 5! large group?

A general quintic normally looks like this:

x⁵+ax⁴+bx³+cx²+dx+e=0

But if we take a more “root-centric” approach we can say that it looks like this:

(x−r₁)(x−r₂)(x−r₃)(x−r₄)(x−r₅)=

x⁵−(r₁+r₂+r₃+r₄+r₅)x⁴+

(r₁r₂+r₁r₃+r₁r₄+r₂r₄+r₃r₄+r₁r₅+r₂r₅+r₃r₅+r₄r₅)x³…− r₁r₂r₃r₄r₅=0

x⁵−(r₁+r₂+r₃+r₄+r₅)x⁴+

(r₁r₂+r₁r₃+r₁r₄+r₂r₄+r₃r₄+r₁r₅+r₂r₅+r₃r₅+r₄r₅)x³…− r₁r₂r₃r₄r₅=0

That is, the constant a,b,c,d,e in the first equation is replaced by a symmetric combination of the roots:

r₁+r₂+r₃+r₄+r₅=a

r₁r₂+r₁r₃+r₁r₄+r₂r₄+r₃r₄+r₁r₅+r₂r₅+r₃r₅+r₄r₅=b

(c and d omitted for brevity)

r₁r₂r₃r₄r₅ = e

r₁r₂+r₁r₃+r₁r₄+r₂r₄+r₃r₄+r₁r₅+r₂r₅+r₃r₅+r₄r₅=b

(c and d omitted for brevity)

r₁r₂r₃r₄r₅ = e

Looking at all the terms in detail, one discovers that interchanging the roots does not affect the equation (try it for b

above for example). This is true for polynomials of any degree. Since

we are able to interchange all the roots, we can draw the conclusion

that the symmetry group for this general quintic is in fact all

permutations, also called S₅ (the symmetric group of order 5).

Fields and Automorphisms

Now

we are going to expand our definition of automorphisms a bit, as they

are more than just functions that permute roots. In the process we need

to introduce something called “fields”. Why would we want to do that,

you say? The reason is, that while working with roots and their

permutations is fun, it’s a bit easier to work with fields and their

automorphisms. It is exactly the same functions, don’t worry, just

another way to look at them.

So, if the equation is, say x²–2=0, instead of working with the roots, r₁=√2, r₂=−√2 we are going to introduce the field Q(√2). This is all the rational numbers Q with an added √2. √2 is called a “field extension”. It looks like this: a+b√2 a,b∈Q. To be able to describe the root of the equation we need the field Q(√2).

For every field extension (and also other mathematical objects) we have

bunch of functions, σₙ, that sends a number to another unique number in

the same field and follow the condition σ(a+b)=σ(a)+σ(b) and σ(ab)=σ(a)σ(b). σ is a function of the extension and does not touch the underlying field Q. These function are called automorphisms. Incidentally, they also permutes the roots. This is because for the root r:

r⁵+ar⁴+br³+cr²+dr+e=0⟹

σ(r⁵+ar⁴+br³+cr²+dr+e)=σ(0)⟹

σ(r)⁵+aσ(r)⁴+bσ(r)³+cσ(r)²+dσ(r)+e=0 (since σ does not touch Q (where a, b, c, d,e lives))

σ(r⁵+ar⁴+br³+cr²+dr+e)=σ(0)⟹

σ(r)⁵+aσ(r)⁴+bσ(r)³+cσ(r)²+dσ(r)+e=0 (since σ does not touch Q (where a, b, c, d,e lives))

This means that σ(r) is also a solution to the equation. And since:

σ(r₁)−σ(r₂)=σ(r₁)+σ(−1)σ(r₂)=σ(r₁−r₂)≠0

the roots are distinct, so we have 5 of them, which must be the original 5. Thus σ must permute the roots.

Of course, this works for an equation of any degree.

Hence:

- We have our equation.

- That equation has a field that might contain an extension of a few radicals

- That field extension has a group, which is a collection of all its automorphisms.

Two Examples of Degree 3

Example 1

Equation: x³−x²−2x+2=0

The roots are (1,√2,–√2) (you can verify this yourself by just plugging them in), so the field must be Q(√2)

Writing down all the ways we can think of to permute the roots (e means identity permutation, it does nothing):

(e)

(√2↔–√2)

(1↔√2)

(1↔–√2)

(√2→−√2 and 1→√2)

(√2↔−√2 and 1↔−√2)

(√2↔–√2)

(1↔√2)

(1↔–√2)

(√2→−√2 and 1→√2)

(√2↔−√2 and 1↔−√2)

Let’s test one: Let (√2↔−√2) be σ₁:

σ₁(√2+−√2)=σ₁(0)=0=σ₁(√2)+σ₁(−√2)

σ₁((√2)(−√2))=σ₁(−2)=−2=σ₁(√2)σ₁(–√2)

σ₁((√2)(−√2))=σ₁(−2)=−2=σ₁(√2)σ₁(–√2)

So far so good. Another one.

Let (1↔√2) be σ₂:

σ₂(√2+−√2)=σ₂(0)=0 ≠ σ₂(√2)+σ₂(−√2)=1+−√2

σ₂((√2)(−√2))=2 ≠ σ₂(√2)σ₂(−√2)=1(−√2)

σ₂((√2)(−√2))=2 ≠ σ₂(√2)σ₂(−√2)=1(−√2)

Apparently σ₂ is not an automorphism, so we will have to scrap it. The other σ runs into similar problems, the only ones remaining are e and σ₁. This is called the cyclic group C₂ since we can only permute in a circle (a very small circle in this case).

Example 2

Equation: x³−2=0

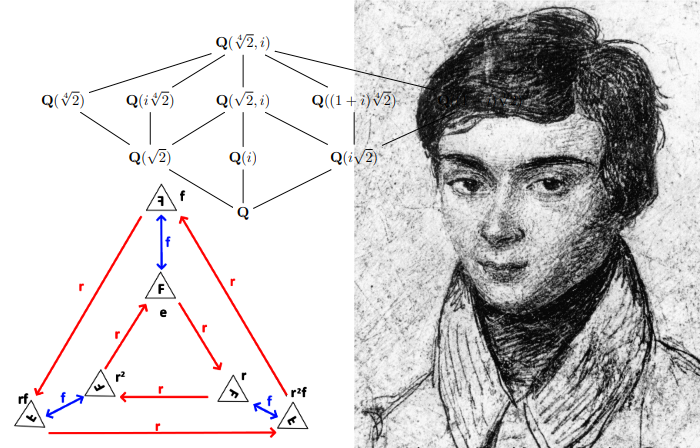

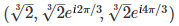

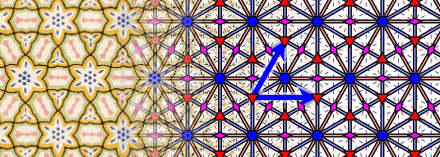

The roots are

so the field must be

using ζ for brevity. This is what it what it looks like:

One

can play around with the root permutations a bit, and will soon notice

that in this case they are all automorphisms. Thus there are 3! automorphisms, which is all the root permutations, so the group must be S₃.

Another

fun thing to notice about the image above is that it looks like an

equilateral triangle and that the automorphisms exactly corresponds to

rotating and reflecting the triangle. If the automorphisms corresponds

to the symmetries of a regular polygon in this way, the group is called a

“Dihedral group”. In this case D₃. Usually the group of all permutations Sₙ is not the same as the dihedral group Dₙ, but in the case of n=3 it is.

Groups

This

seems to be a good place to segue into a little lengthier discussion

about groups. So, groups started out as collections of permutations of

roots, but can also be seen as collections of automorphisms, or

rotations and reflections of symmetrical geometrical objects. Any

collection of functions that changes an object in such a way that it

looks the same can be considered a group. But, we can actually look at

the transformations themselves without bothering about the symmetric

object that they act upon. Much in the same way that we do not bother

about piles of apples when we do arithmetic, we simply follow the rules,

similarly we can define some rules that the transformations of a group

follow, and use them.

The rules are something like this:

If

we first do a transform, and then another one we will get a third

transform that is still in the group. For example, the group C₄ is the group of all rotations one can do on a square. If a is rotating 90∘, b is rotating 180∘ and c is rotating 270∘ then a∗b=c.

Where ∗ means, first do b then a, commonly called multiplication since

it is (kind of) similar to multiplication of numbers. According to the

rule above, c has to be in the group. This is called closure.

There has to be an identity element (e) that does nothing at all.

For every element there has to be a reverse of that element.

Now, we can investigate the features of different group without having to worry about roots or polygons.

Visualizing groups

Two fun way to visualize groups are:

Cayley tables

The above is the Caylay table for an equilateral triangle, the D₃ group. It is all the elements of the group and what elements we get when we multiply them. For example, if we first do a 120∘ rotation (r) and then the same rotation again we get a 240∘ rotation rr=r² as can be seen in the table. If we do a 120∘ rotation-flip rf and a r we end up with just a flip. Notice how the elements f and r does not commute. A group were the element commute is called a abelian group.

This

particular table is still very symmetric though, but that doesn’t need

to be the case. Any scrambling around of the elements that follow the

rules is valid.

Caylay graph

The above is the D₃

Caylay graph. Here the elements are displayed in a way to show how to

get from one element to the next, where the edges are the operations. In

this case a 120∘ rotation and a flip is necessary, these (r and f)

are also called the generators of the group because one can generate

the whole group with them, starting from the identity element.

Usages of groups

Groups

tend to be useful everywhere where there is symmetry. For example, the

wallpaper groups are used to describe symmetric wallpapers. There are

some wallpapers that can be rotated 180∘ and some wallpapers that can be

reflected and some where we can do both, and so on. It turns out that

there are only 17 of them so it is a neat way of classifying wallpapers.

The above wallpapers both belongs a group called p6m.

Another,

more surprising, use of groups is in physics. It seems like the laws of

nature follow certain symmetries. For example, if one transform Newtons

second law F=ma, 10 minutes into the future it is

still the same. That the laws of nature does not change from one day to

the next seems to indicate that they are symmetrical with regard to

time-transformation. Neither do they change from one place to the next

so transformations in space are also allowed. Since it is possible to

transform time and space in arbitrarily small or large chunks the groups

describing these, Lie groups, contains an infinite amount of elements.

Interestingly

it turns out that these symmetries are all related to a conservation

law each. Time symmetry entails the conservation of energy, space

symmetry the conservation of momentum, angular symmetry (nature looks

the same from all angles) the conservation of angular momentum and so

on. This was show by Emmy Noether by just combining the symmetries with

the principle of least action, a law of nature that states that nature

tend to “take the shortest path”.

I

find it interesting how much of all the complexity and apparent chaos

of nature can be explained by such intuitive concepts as “laws of nature

does not change from day to day” and “nature tend to take the shortest

path”.

Back to fields

End of intermezzo, where were we? Right, we were talking about x³−3=0 and its roots and fields.

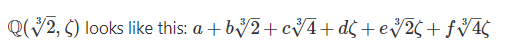

The field of that equation is Q(³√2,

ζ) and it would be natural to think that it looks like this: a+b³√2+cζ,

but that is wrong. The reason for this is that we want our field to be

“Closed”. That is, if we add or multiply two elements in the field we

want to stay in the field. So for example ³√2 and ζ are both in the

above field but ³√2ζ is not.

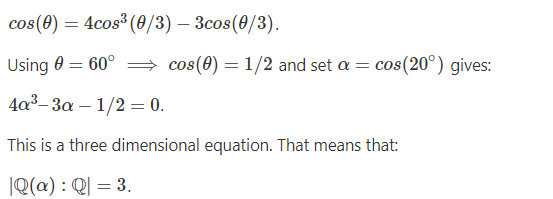

Subfields and subgroups

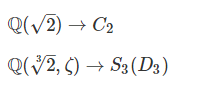

Looking at our examples of degree 3 above we have

It

would seem like the second field and group are more complex than the

first field and group. We can guess this by just counting the number of

terms in the field case or the number of automorphisms in the group

case. But just counting does not seem to really capture what it means to

be complex. Take for example the group C₁₂. Lots of elements, but it only rotates the roots, so it doesn’t really seem all that complex. A corresponding field is Q(e^π/6). It will contain e^π/6,e^2π/6… but again, not very complex.

Worrying

about how complex a group is is going to be key to understanding why

some roots can’t be described by only radicals, remember.

To

get a better way of appreciating the complexity we are going to

introduce the concept of a “Subfield” and a “Subgroup”. A subfield is

when you remove some of the terms but you still have a closed field.

Similarly, a subgroup is when you remove some of the automorphisms but

still have a closed group.

In the first case Q(√2), the only thing one can do is remove the √2 in the field and one of the two automorphisms in the group (we cannot remove (e) and still have a group).

As for the second case Q(³√2, ζ),

it gets a bit more complicated. One can manually distill the

sub-field/groups by just removing elements one at a time and see if the

resulting field/group is closed. After a while we arrive at this:

Interesting,

both the field and the group have four constituents. Now, it would be a

reasonable guess that the subgroups always contains exactly the

automorphisms of the subfields. But they don’t.

Fixed fields

Don’t worry, we’re almost there, it’s just a tiny bit more complicated. To see this, let’s have a look at the field Q(⁴√2, i) and its subfields.

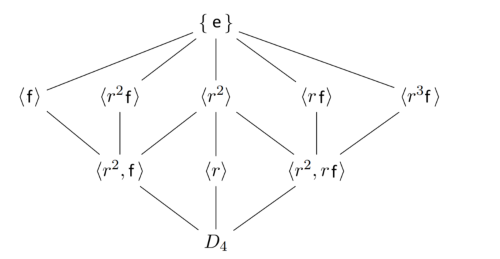

The field Q(⁴√2, i) has the permutation-group D₄ (same as a square). Let’s look at D₄ and it’s subgroups.

The subgroup lattice is upside down in this picture with D₄ at the bottom, I will get to that shortly, but let’s first look at the subfields contra the subgroups. Q(⁴√2, i) has 5 large subfields and 3 small sub-subfields, but D₄ only has large 3 subgroups and 5 smaller sub-subgroups.

It

would seem like there are not enough large groups to permute the 5

large fields. If you were to play around with the subgroups and

subfields you would eventually come to the conclusion that the subgroups

actually permute not the subfields, but rather everything that is not

in the subfields, that they “fix” or do not touch the subfields.

So for example (f) fixes Q(⁴√2) and (r², f) fixes Q(√2).

Why is it this way rather than the other way around, as we first guessed?

I

don’t have an intuitive way of explaining this, the way I see it is

that we discovered it empirically and now we can try to prove it. The

proof goes sort of like this:

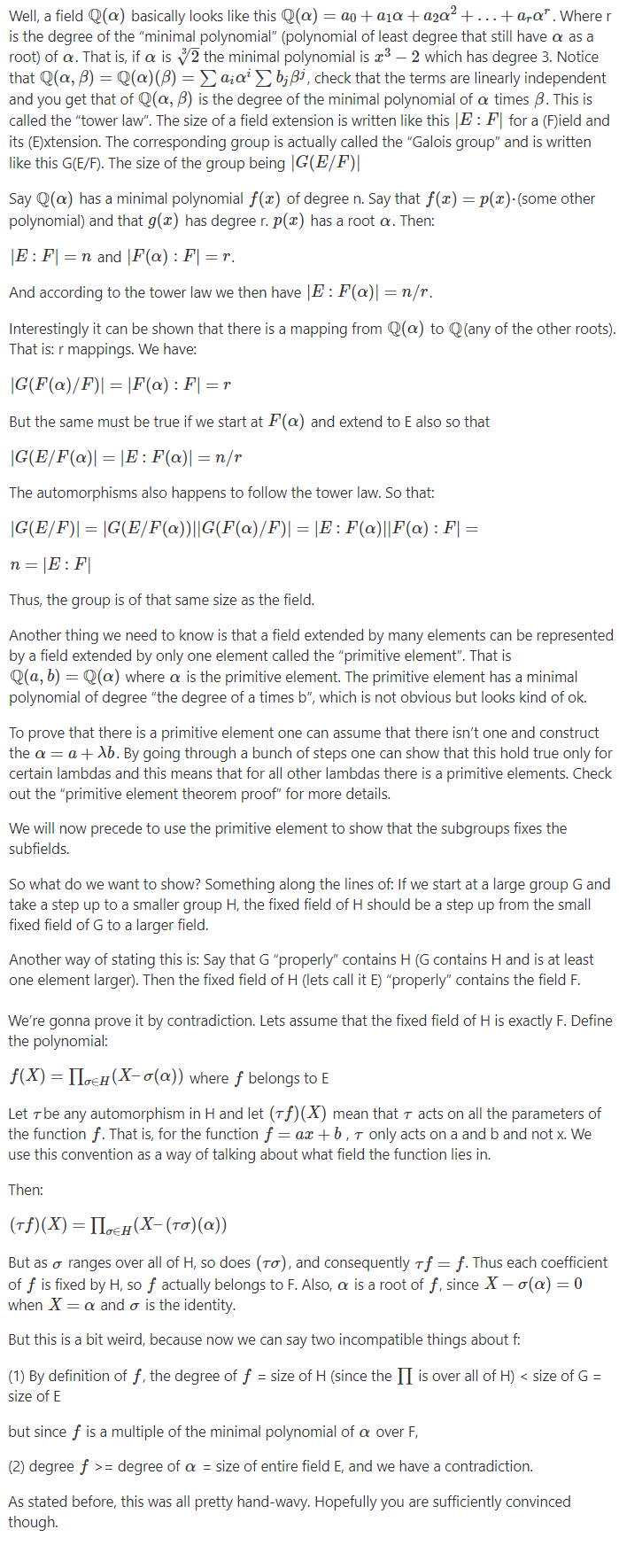

Hand-wavy fundamental theorem of Galois theory proof sketch

We

want to show that if we turn the subgroup lattice upside down we get a

one-to-one correspondence with the subfield lattice where the fields are

the fixed fields of the groups.

First,

I would like to point out that it is reasonable (sort of) that this is

the case. At the bottom group, we have all the automorphisms, who of

course move around everything except Q (fixes Q), and at the top, we only have the e-automorphism, which moves around nothing (fixes everything).

If

we start at the bottom group and remove a few of the automorphisms, the

removed automorphisms will no longer move around a small part of the

field and will thus fix that part of the field. As we remove more

automorphisms a larger and larger part of the field will be unaffected

and thus we will have a larger fixed field.

To

be a bit more rigorous we will need to be able to compare the size of

the group and the field. The group size is, of course, the number of

automorphisms in it. The size of the field is the number of terms. These

two happen to be the same, but why is this the case?

Quotient

Now,

we could look at the S₅ subgroup lattice of the quintic and see that

indeed it looks pretty complex. But in order to tie this together with

radicals we need a way to analyze complexity between groups and its

subgroups. That is: How much more complex is D₄ than C₄ for example? To

do this we introduce the concept of a “Quotient”. A quotient is

basically group division. How does that work?

In

ordinary division we do something like this: To divide 15 apples on 5

persons, we group the apples in the apple-set in 5 equal piles and every

pile will correspond to a person in the person-set. The answer to the

question 15/5 is 3, one of the piles, any pile will do since they are

equal.

A

similar thing happens when we divide groups. To divide D₄ by C₄ we

group the 8 elements of D₄ in 4 equal groups, one for each element in

C₄. How do we make the groups equal? It’s not like the elements are all

identical apples. They can be very different automorphisms for example.

Well, quotients are not always possible for exactly that reason. But

sometimes a group can be divided into “Cosets”. Say we divide D₄ in 4

equal parts with 2 elements in each. If we are lucky we can have 4 piles

of elements where the relation between the two elements are the same in

all of the piles. To be able to do this the original group have to

display a high level of self similarity. To see this, let’s look at a

Cayley graph of D₄.

As

one can see there is in fact a high level of self similarity here. The

top-left, top-right, bottom-left and bottom-right corner all looks the

same. This is our cosets.

So D₄/C₄ is basically one of these cosets, which is C₂. Hence: D₄/C₄=C₂.

Now,

by introducing quotients we actually have a concept of how to build

groups from the ground up. Just as 21 consists of 3 and 7, so do groups

consist of their subgroups. And just as we can get the constituents of a

number by dividing, 21/7=3, so we can get the constituents of a group

by taking the quotient. Since D₄/C₄=C₂, this means that if we have a C₄

group, we have to multiply it by C₂ to get to D₄. Since there is a

correspondence between fields and groups, this will play a role in how

we construct fields.

Radicals

Subgroups of the quintic

Now, I wont show a picture of the group lattice of S₅ because it is too big, but I will say a couple of things about its subgroups. One of the subgroups is A₅ (Alternating group) which is easily checked. To get from A₅ to S₅ we need S₅/A₅=C₂. Thus, we can get there by radicals, but: One subgroup of A₅ is (e), but A₅/e is not a cyclic group. This is true for any An with n≥5 by the way. Thus we cannot get there by radicals and alas, any polynomial of degree≥5 cannot be solved by radicals.

And

that is how Galois, as a teenager, invented the concept of a group to

prove a long standing open question about the unsolvability of the

quintic⁹.

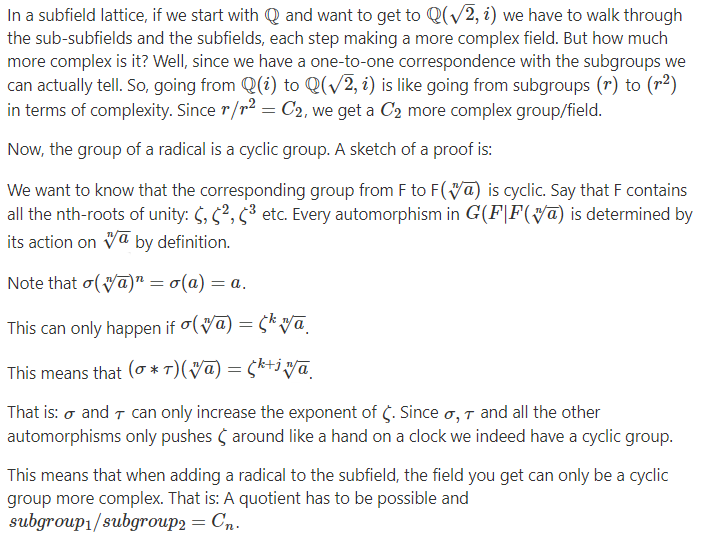

Trisecting the angle

One

fun bonus fact we get from the machinery surrounding Galois theory, in

this case the tower law for fields, is a nice proof of a problem that

stumped humanity since the ancient Greeks, namely: The impossibility of

trisecting an angle with a straightedge and a compass. Apparently the

Greeks loved to draw things in this manner and were curious about the

limitations of the method.

One

example is finding a point in the middle of two other points. To do

this, set the compass on the two point and draw first a circle around

one and then around the other. Use the straightedge as a ruler and draw a

line between the points and then between the points where the circles

cross. The middle is were the lines cross.

But

how does this way of drawing translate to field theory? Well, one can

see the above problem as, say we have a field of two points, (x₁,y₁) and (x₂,y₂). We would like to extend the field to also contain the middle point. To do this we find the intersections of the circles (x−x₁)²+(y−y₁)²=r and (x−x₂)²+(y−y₂)²=r. We get two new points (x₃, y₃) and (x₄,y₄). The line between them is y=(y₄−y₃)/(x₄−x₃)x. The line between the first two points is y=(y₂−y₁)/(x₂−x₁)x. Solve for x to get were they cross.

Apparently, straightedge and compass constructions amount to solving equations of degree one and two.

But what does trisecting an angle amounts to?

The triple angle formula yields:

But

since using a straightedge and compass was the same as solving one and

two dimensional equations the only field extensions possible is 2 for

one operation, and then using the new points we can get to powers of 2: 4,8,16 etc but never 3.

Although it’s impossible to trisect the angle using only a straightedge and compass it is possible using origami.

Solving the general Quintic

It should be said that, although the general quintic cannot be solved by radicals, it can be solved by the “Jacobi theta function”.

References

- Galois Theory for Beginners: A Historical Perspective. Jörg Bewersdorff

- http://pi.math.cornell.edu/~kbro...

- Field Automorphisms

- https://kconrad.math.uconn.edu/b...

- https://faculty.math.illinois.ed...

- Wolfram|Alpha: Making the world’s knowledge computable

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Galois_theory

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/%C3%89variste_Galois

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qkfW35AqrQ&list=PLwV-9DG53NDxU337smpTwm6sef4x-SCLv&index=36