How Students Built a 16th-Century Engineer’s Book-Reading Machine

The bookwheel helps readers browse eight texts at once. The only problem? It weighs 600 pounds.

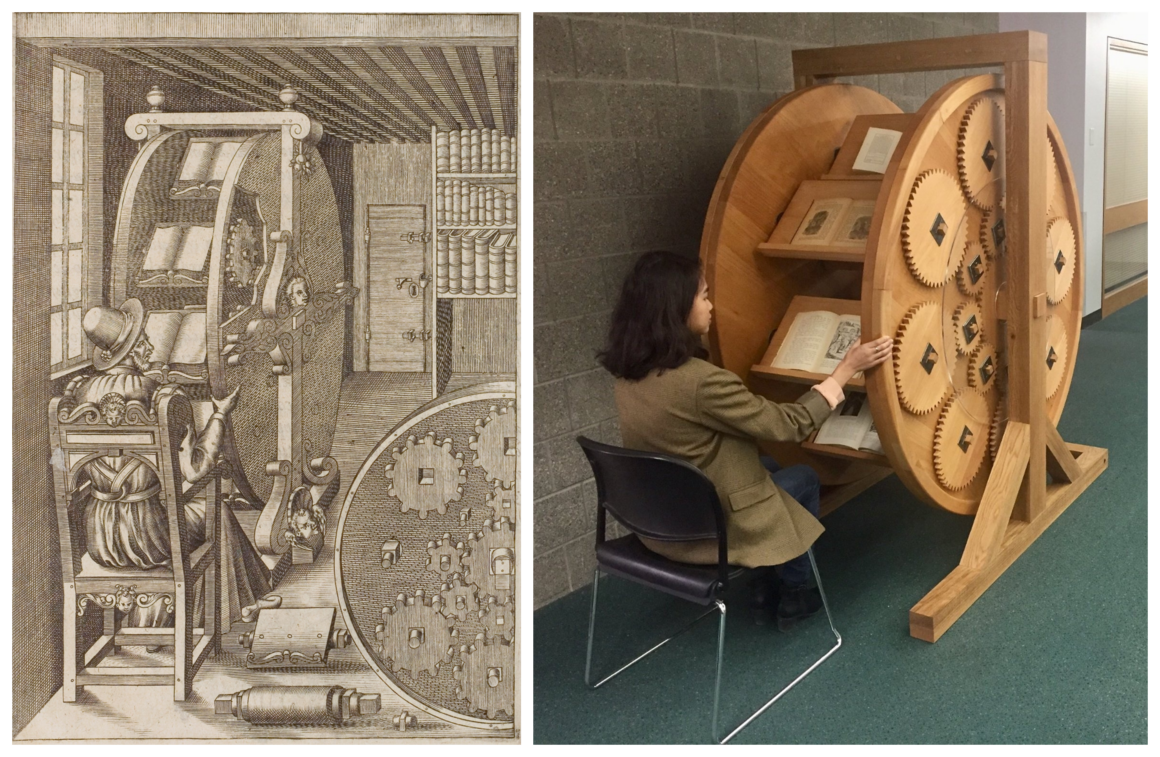

Agostino Ramelli, the 16th-century Italian military

engineer, designed many contraptions for the changing Renaissance

landscape, including cranes, grain mills, and water pumps. But his most

compelling apparatus was one meant to nurture the mind: a revolving

wooden wheel with angled shelves, which allowed users to read multiple

books at one time. “This is a beautiful and ingenious machine, very

useful and convenient for anyone who takes pleasure in study, especially

those who are indisposed and tormented by gout,” Ramelli wrote in Le diverse et artificiose machine, his illustrated magnum opus of mechanical solutions. “Moveover, it has another fine convenience in that it occupies very little space in the place where it is set.”

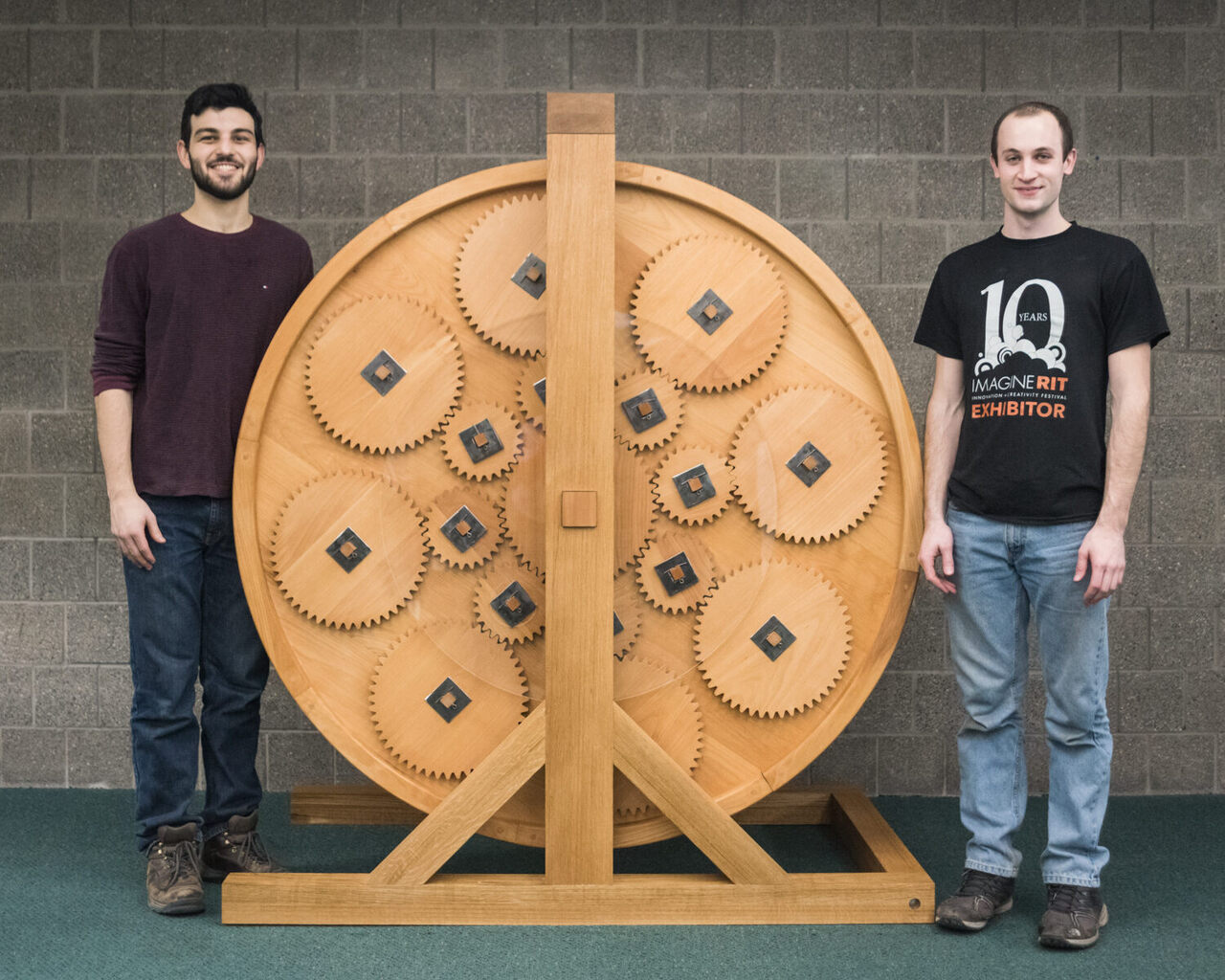

Ramelli never ended up building this

device, but the bookwheel has long intrigued those who study the history

of the book—and in 2018, a group of undergraduate engineering students

at the Rochester Institute of Technology set out to build two. They

began by diligently studying the Italian engineer’s illustration, then

procured historically accurate materials, such as European beech and

white oak. With the help of modern power tools and processes, such as

computer modeling and CNC routing, they brought it to life. “Cutting the

gears by hand would have taken a considerate amount of time,” says RIT

graduate Ian Kurtz. “The actual construction may not have been worth the

time with 16th-century techniques … I think Agostino was more so

showing his understanding of how gear systems worked.”

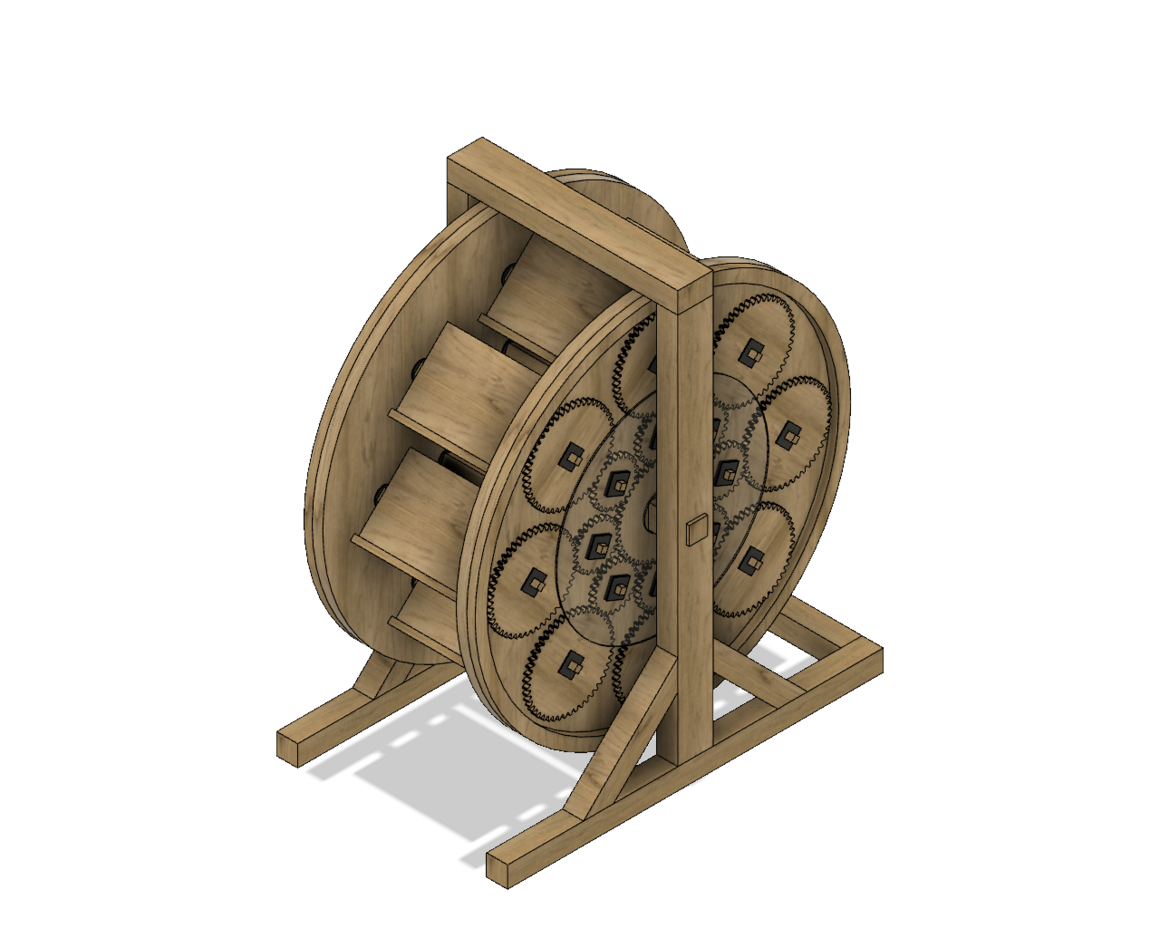

Today, one wheel resides at the Melbert B. Cary Jr. Graphic Arts Collection

at RIT’s Wallace Library, and the other at the University of

Rochester’s Rossell Hope Robbins Library. Each weighs about 600 pounds

and has room for eight books; users can take a seat and spin the wooden

cases, which are carefully weighted to avoid unintended movements. It’s

also worth getting close to observe the core mechanism: a complex,

epicyclic gearing system that consists of outer gears rotating around a

central gear, much like planets moving around the sun.

Ramelli’s design likely inspired similar

wheels that were built in the 17th and 18th centuries, several of which

still exist, but it was probably more complicated than it needed to be.

“There are simpler objects you could build that would accomplish mostly

the same goals,” says Matt Nygren, another former student who built the

wheels. “This is more extravagant than it is entirely practical.” A more

efficient bookwheel, he adds, would be one structured like a Ferris

wheel, with hanging, weighted cradles rather than shelves that move

along a gear system.

Simpler bookwheels did precede Ramelli’s

rotating lectern. Readers in the late Medieval Period could sit by a

book carousel, which rotated open books along a horizontal plane, like a

Lazy Susan, and didn’t require side supports. Steven Galbraith, curator

of the Cary Collection, suspects that the Italian engineer was trying

to improve this design and cater to an increasing need to

cross-reference books, which were often large and heavy. “Through the

16th century, books are beginning to talk to each other a lot more—one

might reference another—so a bookwheel could have been convenient,” he

says. “Some scholars say it’s the beginning of the idea of hypertext,

the idea that a reader can sit in one spot and have access to multiple

texts at once.” (That concept is all too familiar today, in the age of

hyperlinks, search engines, and browser tabs.)

The Cary Collection’s

wheel can be used for individual reading research, but it is also often

used as a teaching tool. At RIT, Juilee Decker, an associate professor

of museum studies, has had her classes design visitor experiences around

the bookwheel. Students have created

videos, games, and instructional material about the device, along the

way developing skills related to digital content curation and audience

engagement. Museums have also expressed interest in the wheel: In

Russia, the Museum of Languages of the World built its own version

according to the RIT team’s plans, which are published online. The University of the Pacific in California has also expressed interest in acquiring one.

Bibliophiles, particularly those who can relate to tsundoku—the

Japanese term describing the habit of acquiring books without reading

them—might want to own Ramelli’s bookwheel, too. But while Kurtz and

Nygren acknowledge that the apparatus is historically significant, they

both believe it doesn’t serve much of a practical purpose, from an

engineering perspective. “I dont think it’s something you should buy and

try and keep in your living room—nowadays there are better tools for

the job,” Nygren says. “But it’s certainly an eye-catching thing, and

one of the fanciest ways I can think of for storing books.”

© 2020 Atlas Obscura. All rights reserved.