Genese Grill on Robert Musil's Intellectual and Creative Life

The years 1921 to 1924 constituted the height of Robert Musil’s participation in the world of theater as both critic and dramatist. He later had plans to collect his writings on theater into a book, which he considered calling Pathology of the Theater or Theater from the Outside. In one notebook entry, he writes that “A pathologist would be able to diagnose a great deal about our time through the theater.”

According to his own avowal, Musil was spurred on to the writing of his two finished plays, The Utopians and Vinzenz and the Mistress of Important Men, by his negative assessment of the contemporary offerings. The Utopians (1921)—which took him approximately ten years to write and which he considered one of his major works—was written, he explained, to “finally, for once, bring some spirit into the controversies surrounding the theater.” It was awarded the prestigious Kleist Prize almost immediately, but was only premiered in 1929, against Musil’s wishes, under the directorship of Jo Lhehrman—a con-man who could almost have come right out of one of Musil’s own plays. Of the second, Vinzenz and the Mistress of Important Men (1923)—a farce that was performed to enthusiastic audiences even before its publication in book form—he reported, “[B]ecause, for once, it just all finally got to be too stupid, I have written a play in 14 days.” Both were written in tandem with his close analysis of contemporary theater and as partial answers to the problems this analysis posed.

We know that late drafts for The Man without Qualities are rife with a variety of utopias, which the author in extremis considered as possible endings for the unfinished (unfinishable) novel. None was more favored than his “utopia of the next step,” a mode of life and thought prefigured in The Utopians and in Vinzenz and the Mistress of Important Men, whereby an action may only be judged by what it brings in its wake, ad infinitum. This utopian state constitutes a radical resistance to closure and final conclusion, manifest in a life of creative aliveness and presence that is represented by another of Musil’s favored utopias: the “Utopia of the Motivated Life.” As Albrecht Schöne pointed out in his brilliant essay on the use of the subjunctive in Musil’s novel, this mode of thought (like the subjunctive case that expresses it) is anathema to rigid (and declarative) systems.

The utopian thinker, the possibilitarian, would, thus, be the first person to be expelled from any established utopia. An ossified utopia, in other words, is already dystopian. The utopia of the next step is not a place or a fixed system, but a resistance to deadly habit and dull conformity, a creative openness, the only state wherein art can be created and experienced—in effect, a utopia without delusive ideals. As Thomas in The Utopians says to an outraged Miss Mertens: “Ideals are dead idealism.” And Musil’s serious engagement with utopian thought, from these early plays and critical writings through the last decade of his life and the last notes for his life’s work, are also a measure of the central social role he assigned to art.

Musil’s two finished plays anticipate the novel’s aesthetic and ethical tension between the self-same and the criminal, creative variations that interrupt its habitual circling. In The Utopians, we find a powerful early metaphor for the tension between patterns and creative alternatives, presented later in the novel as the “two dozen cake pans” into which life is too-often poured and thus limited. In the 1921 play, Regina and Thomas talk about the way they used to walk along the patterns in a carpet (now in the house inherited by Thomas and Maria) as children. Thomas laments:

(Pointing to the patterns Regina has been walking on) One never escapes from what has been predetermined. Sometimes I feel as though everything was already decided in childhood. Climbing, one always comes back to the same place, circling over the emptiness around a predetermined outline. It’s like a spiral staircase.

And yet, like Ulrich and Agathe in The Man Without Qualities, and Alpha and Vinzenz in Musil’s second play, their entire protest against the self-same, their resistance to normal life and its dissatisfying requirements, requires precisely that they do step out of the pre-determined lines in an imaginative act of ethical aliveness. To do so is terrifying and catapults one beyond the pale of normal, conformist social life. The “tragic conflict” between an isolated human being and the vast and terrifying world of unlimited possibilities is described by Thomas in The Utopians as the state of a man alone on his own plank amid infinity; and this image is central enough to Musil’s thinking about theater’s higher aims that he quotes this passage (as the words of “another writer”), in a review of Ernst Toller’s The Lame Man, to illustrate what he deems “the suffering of Everyman, when he notices his loneliness among his fellows in that moment when it is a matter of the deepest things.”

Although Musil’s “farce,” Vinzenz and the Mistress of Important Men is, on its surface, lighter and less challenging than The Utopians, the “feeling of not being at home in the world,” writes Burton Pike, “is not merely a comic pose” for Alpha, the “mistress of important men,” who calls herself an “anarchist.” Nor is it a pose for Vinzenz, her childhood friend, who returns after an unexplained absence of 11 years to play a role similar to that of Anselm in The Utopians: the role of confidence man, but also classic fool, of the actor who reveals that all the other more serious-seeming characters are also living a sort of farce. Neither Anselm nor Vinzenz nor Alpha, on the one hand, nor Thomas and Regina, nor Ulrich nor Agathe in their own way on the other, can commit themselves to easy answers or a solid sense of reality. Thus, the theatrical tricks played by Musil on the audience in his “farce” parody not only the theatrical conventions of his time, but also the conventions and trappings of any semblance of a stable, certain position in real life. Behind what Pike calls Vinzenz’s “sophistic detachment. . . lurks a refusal to commit himself or accept the world. . . [M]ore exactly than any character in Musil’s earlier works, except Anselm and possibly Thomas. . . Vinzenz prefigures Musil’s ultimate man of possibility, Ulrich.”

Maria, in The Utopians, speaks in opposition to her husband Thomas’ relentless rationality: “I think that the only proof for or against a person is whether one rises or sinks in his presence.” And even Thomas, who resists such anti-logical pronouncements, proclaims in the last scene that he, too, is a dreamer, who, like his alter-ego, his creator Robert Musil, is so rational that he must indeed include the realms of dream, of mystery, of uncertainty in his ultimate honest picture of the world. He, like Vinzenz, is another prototype of Musil’s man without qualities, who is simultaneously necessarily a man of possibility, an eternal utopian, whose radical openness is a window on the abyss at the edge of “adventure and ignorabimus.” To another character, Regina, Thomas avows their common ailment and talent in some of the play’s last lines:

I am. . . a dreamer. And you a dreamer. People like us just appear to be unfeeling. We wander, watch what the people who feel at home in the world do. And carry something inside ourselves that we do not sense. A sinking down through everything into bottomlessness at every moment. Without going under. The condition of creation.

And this sometimes uncomfortable, difficult, lonely, radically honest “condition of creation” is not only a cosmological moment, but is, at once, and just as importantly, a “creative condition”—the condition in which life-changing art may be born and experienced.

__________________________________

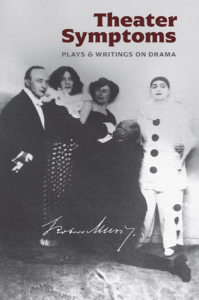

This is an edited excerpt from Genese Grill’s introduction to Theater Symptoms: Plays & Writings on Drama by Robert Musil, translated and edited by Genese Grill. Used with permission of Contra Mundum Press.