“It was an escape route, something entirely private,” Max

Sebald mutters as he rummages through a thick folder of old photographs.

A boy in a white gown and caftan; a graveyard with tilted headstones; a

turn-of-the-century spa: they’re the kind of photographs you’d come

across in a junk shop, leafing idly through a box of postcards. Which is

more or less where Sebald found them. He had been collecting

photographs for years before he began to write, he explains, scouring

the shops in the seaside towns of East Anglia, where he’s lived since

emigrating from Germany in 1970, for images to put in his books—or

rather, to serve as their catalysts. “Not even people in the house knew

what I was up to; I’d just retire to my workshop and potter about. I

think it was these photographs that eventually got the better of me.”

They had got the better of me, too. In fact they were a large part of

the reason I was sitting over a coffee in Sebald’s comfortable,

book-lined study in Norwich. I had come on a literary pilgrimage. The

Emigrants, his English debut, published three years ago by New

Directions, in an elegant translation by Michael Hulse, was like no

other book I’d ever read.

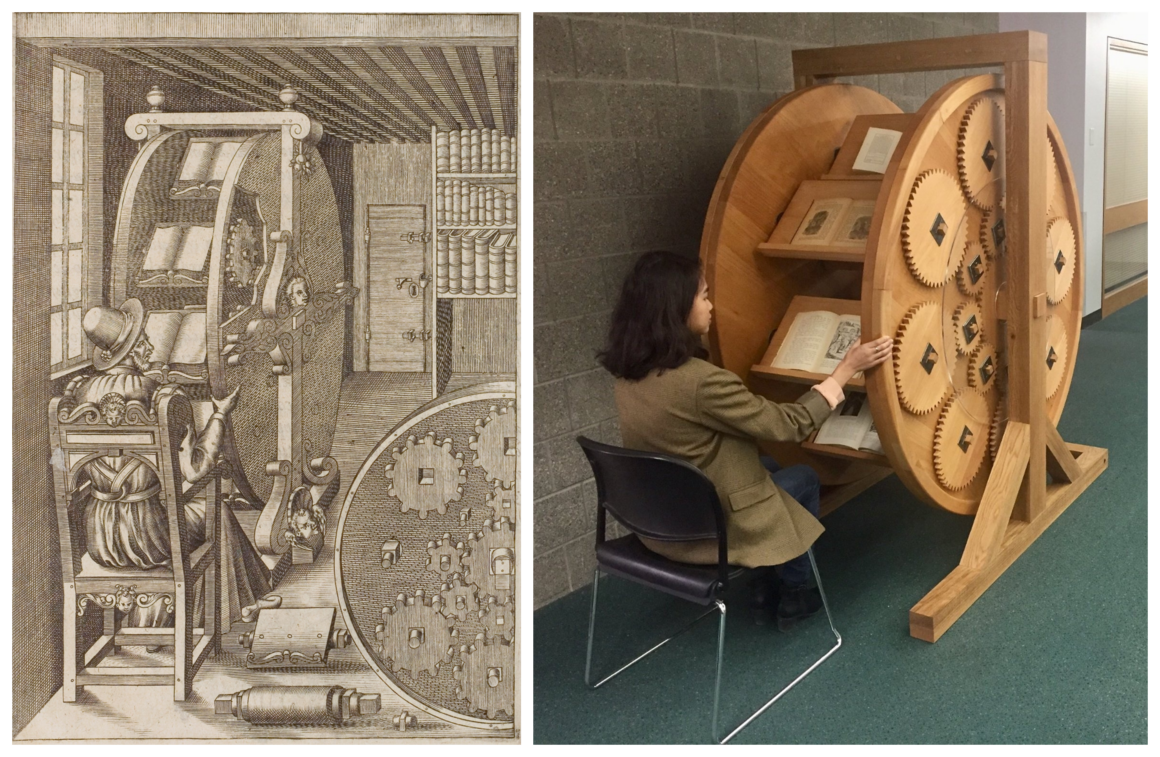

Interspersed with the text—a sequence of biographical narratives

about Germans exiled by the Holocaust—were captionJess photographs that,

out of context, made no sense.

Why a grass tennis court with leafless winter trees in the

background? Why a Jewish cemetery overgrown with vines? Why the spire of

the Chrysler Building and the Brooklyn Bridge? And who were the people

in these photographs, who seemed to have no connection to one another? A

family around a dinner cable; children in a classroom; a quartet of

goggled passengers in a roadster: they have the musty air of snapshots

in a family album, where long-forgotten faces, anonymous and indistinct,

gaze up from the yellowing page—“what one imagines lost souls look like

in Sebald’s haunting description.

His new book,

The Rings of Saturn, supposedly a

compilation of random notes begun when the author was in a mental

hospital, is a continuation of this peculiar hybrid form. The elusive

narrator. a meticulous amateur historian of East Anglia, wanders the

countryside with a rucksack on his back, recounting in the digressive

but hypnotic prose that is Sebald’s trademark the lore he’s gathered

about the area’s medieval past, the long-vanished inhabitants of its

derelict manor houses, the archaeology of its quaint seaside villages.

Like

The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn is illustrated with mysterious photographs that play off and clarify the equally mysterious text.

And like its predecessor, it’s told in the voice of a nameless I

whose identity is indeterminate, his odd soliloquy on the ravages of

history counterpointed by passages from the works of Swinburne,

Chateaubriand, Borges ("I asked Bioy Casares for the source of this

memorable remark, the author writes ... “) and Joseph Conrad, who once

sailed the North Sea coast in the days when he was still the sailor

Jozef Korzeniowski.

From a detailed summary of Conrad’s early life, Sebald segues to the

novelist’s traumatic journey into the deepest recesses of the Belgian

Congo, which would inspire his masterpiece

Heart of Darkness—then

abruptly returns to an account of his own travels, his forward

narrative progress interrupted by associations with Belgium:

At all events, I well recall that on my first visit to Brussels in

December 1964 I encountered more hunchbacks and lunatics than normally

in a whole year. One evening in a bar in Rhode Sr Genèse I even watched a

deformed billiard player who was racked with spastic contortions but

who was able. when it was his turn and he had taken a moment to steady

himself, to play the most difficult cannons with unerring precision .

The hotel by the Bois de la Cambre where I was then lodging for a few

days ...

And so on, proceeding from a brisk inventory of the hotel ’s

ponderous furniture to a consideration of the ugly monument the Belgians

erected to commemorate the Battle of Waterloo.

For Sebald, the discontinuities of the unconscious are the mainstay of his art.

Sebald, who is fifty-four, speaks with a pronounced German accent,

but his English. after nearly three decades, is sophisticated and

precise. (How many native English speakers know how to use the word

apodictic

in a casually tossed-off sentence?) With his thinning mane of white

hair, rimless glasses and bushy mustache, he resembles the Frankfurt

theorist Walter Benjamin. On this lace winter day he’s dressed in

nondescript corduroys and a bulky sweater; only the mustache and the

cigarette he’s smoking in a holder give off a hint of his Continental

origins. He introduces himself by his nickname- Max.

Sebald’s books elude easy classification. Are they fiction or

nonfiction? History or a Borgesian fabrication built upon fact? His

publisher, hedging, has resorted to the dual category of

fiction-literature. “It’s hard on publishers,” he concedes.

“You have to make sure it doesn’t get in the travel section.”

When I try to pin him down, he becomes slyly evasive. “Facts are

troublesome. The idea is to make it seem factual, though some of it

might be invented.” In the end, truth as a historian or biographer

understands the term is irrelevant to him. “I just want to write decent

prose. Whatever it is—biographical, autobiographical,

topographical—doesn’t matter. I have an aversion to the standard novel:

‘She said, and walked across the room’—there’s something trite about it.

You can feel the wheels turning.”

Sebald’s books are resolutely plotless. Their narrative line follows

the contours of the unconscious. His method is to build up a collage of

apparently random details—stray bits of personal history, historical

events, anecdotes, passages from other books-and fuse them into a story;

Sebald, borrowing the term from Claude Levi-Strauss, calls it

bricolage. The effect is a kind of organized free association, as if one were reading a sequence of dreams instead of a linear narrative.

The Emigrants begins: “At the end of September 1970, shortly

before I took up my position in Norwich, I drove out to Hingham with

Clara in search of somewhere to live.” But Clara will soon be left

behind, and the narrator—

I—will never be more than a shadowy pronoun, like the narrator of

The Rings of Saturn,

who opens his story: in August 1992, when the dog days were drawing to

an end, I set off to walk the county of Suffolk, with the hope of

dispelling the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed

a long stint of work.”

Who was this authorial presence, this enigmatic

I? The biographical note appended to

The Emigrants

was fuller than most. It revealed that Sebald was born in Wertach im

Allgaü, Germany, in 1944; that in 1966 he became an assistant lecturer

at the University of Manchester; that he’d taught at the University of

Ease Anglia since 1970; that he’d served as Director of the British

Centre for Literary Translation from 1989 to 1994. But it still left a

great deal unsaid; even the author’s full name-Winfried Georg-could only

be teased out by consulting the copyright page. What fascinated me was

the inconcrovenible fact yielded up by his birthdate: Sebald wasn’t

Jewish. How many Jews born in Germany in 1944 survived Hitler’s ovens?

The Emigrants wasn’t

the work of a survivor, then; it was something far more rare: the work

of a disinterested moral witness. Or was he? “Such a life is somehow

still touched with a smudge, or taint, of the old shameful history,”

Cynthia Ozick observed in a review of The Emigrants; and “the smudge, or

taint—or call it, rather, the little tic of self-consciousness—is there

all the same, whether it is regretted or repudiated, examined or

ignored, forgotten or relegated to a principled indifference.”

The Emigrants is an anomaly in so-called Holocaust literature.

a book that goes to the heart of that catastrophic event by hovering

on its periphery. Like Aharon Appelfeld, whose novels tend either to

prefigure the Holocaust or to dwell on its lingering aftermath, Sebald

chronicles the ripple effect of recent German history on four indirect

victims: a retired English doctor who fled the pogroms in Eastern Europe

and, never having felt at home in his adopted land, eventually commits

suicide; a German primary-school teacher in the 1950s who also ends a

suicide; a cluster of the author’s relatives who emigrated to America in

the 1920s; and aJewish refugee painter whose parents were murdered by

the Nazis. Each of these stories is tangential to the Holocaust, yet

each of the protagonists is fatally implicated in it, caught up, however

obliquely, in the eradication of the Jews. Visiting an abandoned Jewish

cemetery in Kissingen, the anonymous narrator encounters “a wilderness

of graves, neglected for years, crumbling and gradually sinking into the

ground amidst call grass and wild flowers under the shade of trees,

which trembled in the slight movement of the air.” Soon the graves

themselves will vanish.

The great theme of The Emigrants is the hidden consequences of the

Holocaust-not only the trauma of the survivors, the allocation of guilt,

the Germans’ struggle with their Nazi past, or even the new insights

about human nature that it forced upon us, but its eerie aftereffects,

the veneer of normality that encourages us to forget. “I felt

increasingly that the mental impoverishment and lack of memory that

marked the Germans, and the efficiency with which they had cleaned

everything up, were beginning to affect my head and nerves,” Sebald

writes in the last chapter, recounting his visit to the abandoned

graveyard at Kissingen: “It was not possible to decipher all the

chiselled inscriptions, but the names I could still read-Hamburger,

Kissinger, Wertheimer, Friedlander, Arnsberg, Auerbach, Grunwald,

Leuthold, Seeligmann, Frank, Hertz, Goldstaub, Baumblatt and

Blumenthal-made me think that perhaps there was nothing the Germans

begrudged the Jews so much as their beautiful names, so intimately bound

up with the country they lived in and with its language.” Like Daniel

Gold hagen, the controversial author of

Hitler’s Willing Executioners,

Sebald believes the Holocaust was uniquely German; it was no accident

that it happened there. “There is something about Germans, which for

lack of a better word we’ll call cowardice,” he says, groping for an

explanation of the collective blindness that enabled the Nazis to

flourish. “They have a habit of avoidance. People don’t want to know.

It’s as if it never happened. In England, the sixteenth, seventeenth,

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are still visible; in London, there

are tangible layers of history. In Germany, partly because of the

destruction of the cities and partly because of the way in which Germany

deals with its own past, their history is much less present. It has

been, as it were, neutralized. The cities all look like each

other-pedestrian zones, wretched malls with trees growing out of

concrete pots, the same shops ... ”

Yet for all his moral outrage, Sebald isn’t a polemicist; his intent

is less to build a prosecutorial case against Germany, as Goldhagen

does, than to puzzle over the transience of human life. However

murderous the Nazis’ intent, they were only accelerating the inevitable.

“From the earliest times, human civilization has been no more than a

strange luminescence growing more intense by the hour, of which no one

can say when it will begin to wane and when it will fade away,” he

writes in his new book. All things pass; nothing endures. This is the

lesson so powerfully brought home in

The Rings of Saturn. Where

The Emigrants showed how widely the Holocaust emanated from its epicenter, how efficient was the destruction it unleashed,

The Rings of Saturn

forces us to loosen our grip on the illusion that anything is

permanent. As he sifts through history, cataloging one historical

catastrophe after another, Sebald conjures up the image of a globe

engulfed in serial chaos: low-lying pons are swallowed up by storms;

rainforests are leveled by fire; entire populations are massacred in

obscure distant wars. East Anglia itself, Sebald’s quaint and docile

corner of England, was only half a century ago the staging ground for

the war against Hitler:

Time and again, as one walks across the wide plains, one passes

barracks, gateways and fenced-off areas where, behind thin plantations

of Scots pines, weapons are concealed in camouflaged hangars and

grass-covered bunkers, the weapons with which. if an emergency should

arise. whole countries and continents can be transformed into smoking

heaps of stone and ash in no time.

Saturn, formally speaking, is like The Emigrants: the signature

photographs of people and landscapes described in the text; the

rambling, nearly free-associative meditations and long incantatory

sentences unwinding with slow serpentine grace; the ruminative

first-person voice. But the narrator is a more visible figure, more

bodied forth as a literary character on the order of Dostoyevsky’s

Underground Man or Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, to whom he compares himself. As

1 made my way through its densely allusive pages, I was put in mind of

Mallarme’s dictum that everything in the world exists to be put in a

book. The depredations of Dutch elm disease, the lifespan of the

silkworm and the social transformation wrought by the silk industry in

the eighteenth century, even a five-page discourse on the physiology and

migratory habits of herring, all find their way into Sebald’s weave.

The leitmotiv that binds his digressive excursions into the past in The

Rings of Saturn is the same one that dominated The Emigrants- “scenes of

destruction, mutilation, desecration, starvation, conflagration.” It’s

not a pretty picture .

•

Sebald’s self-exile makes him exotic-"How many German writers live in

East Anglia?” he notes—but it also makes him a representative case.

From Eliot in England to Joyce in Paris and Nabokov in the United

States, the writers who dominate the contemporary canon have been

essentially stateless, citizens of a domain that requires no cultural

passport; George Steiner has named this condition “unhousedness.” Or, as

Sebald himself put it to me in his occasionally clumsy but invariably

accurate English: “Paradigmatically postmodern writers are often

operating on linguistic borderlines.” To this experience he has brought a

prose so lapidary, so particular, so loaded with concrete detail that

it has the impact of a photograph. “I heard the woodwork of the old

half-timber building, which had expanded in the heat of the day and was

now contracting fraction by fraction, creaking and groaning,” he writes

in

The Rings of Saturn, recounting a night spent in a country inn. He goes on:

In the gloom of the unfamiliar room, my eyes involuntarily turned in

the direction from which the sounds came, looking for the crack that

might run along the low ceiling. the spot where the plaster was flaking

from the wall or the mortar crumbling behind the panelling. And if I

closed my eyes for a while it felt as if I were in a cabin aboard a ship

on the high seas, as if the whole building were rising on the swell of a

wave, shuddering a little on the crest, and then, with a sigh,

subsiding into the depths.

Like his great stateless predecessor in the famous preface to

The Nigger of the Narcissus, he wants, “above all, to make you see.”

•

Others before me had fallen under the spell of Sebald’s work. The

paperback edition of The Emigrants carried effusive blurbs from Susan

Sontag and A.S. Byan, and it had showed up on several writers’ Best

Books of 1997 lists in England.

But hardly anyone I canvased in America had heard of him; the book

seemed to be circulating samizdadike from hand to hand. (I’d heard about

it from a friend.) Like Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader, a small gemlike

novel about a love affair in Nazi Germany and its eerie postwar

reverberations, Sebald’ s masterpiece had acquired a readership in the

old way, without publicity or drumbeating on the part of its publisher, a

venerable literary house that tends to concentrate on poetry. No one

seemed to know much about the author.

When I asked his London agent, Victoria Edwards, what he was like,

she said she’d never met him. Like his peripatetic narrator, he liked to

go for walks in all weather; twice when I called, his wife told me he

was “out with the dogs.” The notion of a literary profile bewildered

him. “I am glad you liked The Emigrants and quite astounded that you

propose to come all the way to talk to me,” he’d written in reply to my

request for an interview.

He had turned out to be less forbidding than I’d anticipated.

When I arrived in Norwich that morning on the train from London, Max

had been waiting at the gate. I recognized him from the photograph on

the back of

The Emigrants. He was shy at first as we drove

through the streets of Norwich in his rattletrap Peugeot, but he soon

grew talkative, pointing out the eleventh-century Norman cathedral that

towers immensely over the town and going on about his dealings with

publishers , agentS, advances-a writer’s shoptalk. “My publishers would

say to me that they had sold foreign rights to France or Italy—‘We got

you five hundred pounds’—and then I’d never hear another thing about it

again,” he complained, grousing like a journalist at Elaine’s. He struck

me as worldly. in a quiet, unobtrusive way, possessed of a steely ego

and not afraid to engage in public debate on highly charged issues. When

he gave a series of lectures on the history of the Allies’ air war

against the Reich in Zurich last year, he told me, it provoked intense

coverage in the German media. “I felt that I’d touched on a raw nerve,”

he said without apparent regret.

Sebald’s house, The Rectory, is a redbrick Victorian manor with tall

windows and a manicured lawn in a suburban cul-de- sac on the outskirts

of Norwich. He renovated it himself, by hand, over half a dozen years.

Trim and tidy, it seemed the very antithesis of his dark, broodingly

apocalyptic prose.

While we settled down in the study to talk, his wife, Uta, a handsome

fiftyish blond—they met as students at the University of Freiburg-was

visible through the windows, mowing the lawn with a tractor mower.

Morris, their big black dog , dozed on a cushion. The pristinity of the

room-volumes of German literature neatly arranged on the shelves; a

blindingly white rug; a leather club chair and couch; a wood-burning

stove painted fire-engine red-unnerved me for some reason.

The only eccentric touch was the row of hats hanging on the wall:

they reminded me of one of those somber, depopulated museum

installations of Joseph Beuys, where the once-living form is represented

by an old coat or a scrap of fur. Otherwise he could have been a

bourgeois shopkeeper in his suburban domicile. “I like to try to lead a

normal life,” he told me-and for all intents and purposes he does. Uta,

who brings us tea and cookies, is engaging and friendly; the Sebalds’

daughter, Anna, twenty-six, is a schoolteacher living nearby. б’She’s

not all that interested in my work,” Sebald maintained.

I asked him about a sentence from The Emigrants that had stayed with

me: “When I think of Germany, it feels as if there were some kind of

insanity lodged in my head.” In the fifties and early sixties, he

explained, when he was growing up, the Nazi era was regarded as an

almost normal episode in German history. “In 1939, my father was

unemployed. He had the good fortune, as he saw it, to be admitted to the

Weimar One Hundred Thousand Man Army. Once you got in there, you had

prospects, a job.” His father fought in the Polish campaign, and was

briefly interned in a French POW camp toward the end of the war, but

rarely talked about his experiences. Sebald’s childhood was, by his own

account, ordinary. “I never thought much about anything at all. I had a

penchant for reading.” he says, giving the word a French pronunciation,

’"but otherwise I was the same as everybody else-skiing and all the rest

of it.” He painted a rather withering portrait of his parents as

bourgeois burghers. “My father was a clerk in an office until the

fifties, and then joined up in the army again. He retired early, as one

does in that profession, and has done nothing for the last forty years

but read the newspaper and comment on the headlines. He has a critical

bent of mind, and very pronounced opinions about the issues of the day.”

What does he think of his son’s work? “He took a certain interest when

there was public attention; then he seemed to be jolly pleased about

it."’ It wasn’t until Sebald entered the University of Freiburg that he

became aware of the war’s unspoken legacy. ббconditions for students

were very poor,” he recalls. “German colleges in those days were

unreformed, completely overrun, undersourced. You would sit in lectures

with 1,200 other people and never talk to your teachers. Libraries were

practically nonexistent.” But what troubled him more than the

overcrowded conditions was the conspiracy of silence surrounding the

Nazi era. “All my teachers had gotten their jobs during the Brownshirt

years and were therefore compromised, either because they had actively

supported the regime or been fellow travelers or otherwise been silent.

But the strictures of academic discourse prevented me from saying what I

wanted to say or even investigating the kinds of things that caught my

eye. Everyone avoided all the kinds of issues that ought to have been

talked about. Things were kept under wraps in the classroom as much as

they had been at home. I found that insufficient.”

He transferred to a university in Switzerland, and then applied for a

teaching job in Manchester. “I knew nothing about Manchester. I hardly

knew English. and had no intention of staying. I thought I would just be

there for a year.”

In

The Emigrants, Sebald provides a vivid account of his arrival in that sooty industrial metropolis aboard a night flight from Kloten:

Once we had crossed France and the Channel, sunk in darkness below, I

gazed down lost in wonder at the network of lights that stretched from

the southerly outskirts of London to the Midlands, their orange sodium

glare the first sign that from now on I would be living in a different

world . . .. By now, we should have been able to make out the sprawling

mass of Manchester, yet one could see nothing but a faint glimmer, as if

from a fire almost suffocated in ash. A blanket of fog that had risen

out of the marshy plains that reached as far as the Irish Sea had

covered the city. a city spread across a thousand square kilometres,

built of countless bricks and inhabited by millions of souls, dead and

alive.

Sebald was forty-five when he began to write. “I had quite a

demanding job. There was never rime to write.” I asked him if he had

ever been in therapy: his work is so apparently random in the way it

leaps from subject to subject that it mimes the process of free

association. “I never got round to it,” he answers. “My therapy consists

of reading other case histories.” But in the seventies and eighties he

spent summers at a mental clinic near Vienna, a sort of therapeutic

vacation from the rigors of teaching that would also serve as research;

the director, Leo Navratil, encouraged his patients to draw or paint,

and had published a book of poems by one of his inmates, Ernst Herbeck,

that Sebald found “mind-boggling.”

He continued: “I thought it would help me understand some of the

basic conditions in creativity to go there.” He hadn’t gone as a

patient? “Oh, no, no. Writing itself is an insane occupation: hard,

compulsive, most of the time not pleasurable.

There is always the desire to find out how one is made up, to get to

those layers chat are out of sight; but I would find it hard to write

anything confessional. I prefer to look at the trajectories of other

lives that cross one’s own trajectory— do it by proxy rather than expose

oneself in public …

•

I was startled to encounter in

The Rings of Saturn

a description of someone I actually knew, the poet and translator

Michael Hamburger, who retired from London some years ago to a rural

cottage in Middleton, a hamlet about twenty miles from Sebald’s house. I

had met him in the early seventies, when I was a student at Oxford; but

1 hadn’t seen him in more than twenty years, and proposed to Sebald

that we go for a visit.

On the way, we stopped off in Southwold for lunch at the Crown Hotel.

It was a snug establishment, with rough-hewn wooden cables and

small-paned bay windows that looked out on the main street of the town.

On this wintry February day, it was full of elderly people in cardigans;

Southwold is a popular retirement community for BBC executives, Sebald

explained. He seemed at ease in the comfortable dining room.

He said that the Crown was one of his regular haunts, and that he

often stopped in for a night or two “to get away from the routine.” It

was a curious thing: his work is so relentlessly grim chat it verges on

the comic, but Sebald himself appeared wryly cheerful, even when he was

discussing the work of Primo Levi or describing a book on euthanasia in

Nazi Germany that he’d just read. ("An asylum in Kaufbeuren was still

dispatching victims three weeks after the Americans arrived.") Like most

writers I know, he showed a lively interest in real estate; as we

strolled around the town after lunch, he lamented that he should have

bought one of the grand old houses on the village square when he first

arrived in the area; now they’re too expensive. ’бIn his writing, he

comes across as a melancholy man,” Michael Hulse told me, “but he’s

really a very funny man:’ When I commented on this apparent

contradiction between his somber world view and his equable disposition,

he shrugged. ’"One is born with a certain psychological constitution,”

he said, referring to himself in the third person as if to deflect any

insinuation of egotism, “and then one discovers that life is partly

dispiriting and partly exhilarating in its oddness.” He invoked

Flaubert’s famous advice to be a bourgeois in life and a madman in art.

“I want to hold on to my job, so I’m not condemned to this activity. If

left to my own instincts I might well have become a recluse.”

He wanted to show me the Sailors’ Reading Room on the promenade. I

instantly recognized the navigational instruments and barometers on the

walls, the bartered leather armchairs and ships’ models, from Sebald’s

description in

The Rings of Saturn. Two old men were playing pool in the backroom.

It felt odd to be touring the very locales so vividly conjured up in

The Rings of Saturn—it

was almost as if I myself had stepped into the pages of his book. A

writer in exile, Sebald had acquired as deep a sense of place as any

writer I know. Tramping the lanes and meadows of East Anglia, he had

steeped himself in its lore. “The intriguing thing for me about Suffolk

is that it is untouched by history, as the whole country is in a sense,”

he remarked ... There hasn’t been a war on English soil since the

seventeenth century.” I asked if he ever felt homesick for Germany. He

answered: “Yes, until I go there. When I first came here I had no

intention of staying in Manchester. I still go over several times a

year. and have made repeated attempts to return to Germany, but I always

end up coming back here.” At one point in the late 1980s he worked for a

German cultural institute, and last year he was offered a position in

creative writing at the University of Hamburg. “I did not want to be

drawn into the German culture industry. I do feel uncomfortable in

Germany. It feels like a cold country.”

It was growing dark as we left town and pulled into a muddy driveway

beside an ancient farmhouse . Michael, in a worn corduroy jacket, opened

the heavy wooden door. He ’s in his mid-seventies now, but he looked

nearly the same as he did when I last saw him, frail and wrenlike; even

his hair is still dark. His beautiful wife, the poet Anne Beresford, had

also aged well. He welcomed us into a cold, dank room with a low

heavy-beamed ceiling, leaded windows, and a charred stone fireplace—a

room out of a Brontë novel. There were books everywhere—in a closet, on

floor-to-ceiling shelves, piled up by the stairs that lead to the study.

The house is “part Stuart, part Tudor,” he said. “It’s falling down

around us, but it will probably see us out.”

It was dark now. The wind rattled the windows. Suddenly I felt far

away from home, the way I used to feel when I lived in England

twenty-five years ago, before there were phones everywhere and central

heating and people flew back and forth across the Atlantic for a

weekend. But a few minutes later, it was time to go; the spell was

broken. Back in the car, we headed for the Norwich train station. Sebald

was talking about the family tragedies that had lately befallen so many

of his friends. “For years I didn’t know anyone who was ill,” he said.

“Now it’s all around me.”

That night, back in my room in London, I looked up the pages about Michael in

The Rings of Saturn. I had read the book in galleys, and hadn’t seen the photographs before .

There were two of Michael’s study—one showed his book—crowded writing

desk and the ancient small-paned bow window behind it; the other showed

a mass of books piled up beside a door. It was strangely moving to find

images so recently imprinted on my own consciousness staring up at me

from the page. Suddenly I thought of a book I’d read as a child: C.S.

Lewis’s

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, in which a gang

of children climb through a closet door and find themselves transported

to some other world. That’s what being with Max was like.