How Storytellers Use Math (Without Scaring People Away)

Dan Rockmore on Infinite Powers and The Weil Conjectures

Our current pandemic is not a first excursion into remote learning. Many may know of the origins story of calculus, born over Isaac Newton’s retreat to the countryside from Cambridge University during The Great Plague of London in the 17th century. This, as well as the broader history and wide applicability of mathematics’ successful wrestling match with the subtleties of infinity, is the subject of Infinite Powers by well-known math popularizer Steven Strogatz. Lesser known is the story of mathematician André Weil’s breakthroughs in understanding prime numbers while interned in a French military prison camp in 1939, a piece of Karen Olsson’s The Weil Conjecture, an elliptical tale that interweaves and integrates mathematics and memoir. These books share the quality of illuminating deep mathematical ideas for the broader public, but by very different paths. One is unashamedly instructive and hinged on the promise of revelation of a deep idea that is surprisingly central to our everyday lives, while the other the revelation of a life through an elliptical and personal rediscovery of a deep idea. One is a tale of how mathematics has changed all of our lives, the other a tale of how mathematics changed one life. You’ll learn a lot from both of them—about math and other things too.

*

Writing about mathematics presents some special challenges. All science writing generally amounts to explaining something that most people don’t understand in terms that they do. The farther the science is from daily experience, the tougher the task. When it comes to mathematics, its “objects” of study are hardly objects at all. In his famously heartfelt if somewhat dour memoir A Mathematician’s Apology, the mathematician G. H. Hardy describes mathematicians as “makers of patterns.” While all sciences depend on the ability to articulate patterns, the difference in mathematics is that often it is in the pattern in the patterns, divorced from any context at all, that are in fact the subject.

None other than Winston Churchill was able to tell us how it feels to have tower of mathematical babble transformed to a stairway to understanding: “I had a feeling once about Mathematics—that I saw it all. Depth beyond depth was revealed to me—the Byss and Abyss. I saw—as one might see the transit of Venus or even the Lord Mayor’s Show—a quantity passing through infinity and changing its sign from plus to minus. I saw exactly why it happened and why the tergiversation was inevitable, but it was after dinner and I let it go.” Let’s assume it wasn’t just the whiskey talking.

*

There is an art to being a good tour guide of the depths of mathematics. Subject matter is key; infinity is fertile ground for both appreciating and explaining some mathematics. That’s the conceit of Steve Strogatz’s new book Infinite Powers (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Seeing the infinite in the quotidian has been not only the source of great poetry and literature and philosophical debate, it has also been the source of one of the great mathematical discoveries/inventions/creations of humankind: the calculus, of which he writes, “If anything deserves to be called the secret of the universe, calculus is it.” He wants you to appreciate calculus as an achievement that came from the willingness to imagine the infinite, wrestle with it, and ultimately tame it. The key to this is something that Strogatz calls “The Infinity Principle”—a problem-solving technique of seeing infinity in the everyday and then either dividing things into an infinity of infinitesimals or adding them all up—that is the reason that calculus has enabled so many mathematical and scientific discoveries.

Poor finite creatures that we are, we don’t have much direct experience with infinity. Some of the early attempts to consider infinity in terms that we do understand, most famously by the philosopher Zeno, caused more confusion than clarity: “How can I get from here to there if no matter where I am I need to go half the distance first?” Fortunately, others brought some less fuzzy thinking to the problem, even in early days. Archimedes was among those who attempted to make mathematics of this in the Platonic context of finding areas of curved figures by adding up an infinity of infinitely thin rectangles. We get closer to language of the everyday when we revisit the Infinity Principle as an approach to the understanding of change in time. Newton’s laws of motion are written as the cause and effect of infinitesimal change (so-called “differential equations”) in the position and velocity of objects, and the implications of these laws require the adding up of an infinity of such infinitesimal changes (integration). The “mystery of curves, the mystery of motion, and the mystery of change,” Strogatz calls them, and with the last two of these we’re on ground where we’re speaking the same language.

Strogatz is a terrific storyteller and patient teacher. Examples and illustrations are drawn from the everyday—including one that is actually about the length of the day as it varies over the year. Packing overhead bins, Usain Bolt dashing down the track, and even cinnamon raisin bread make illuminating appearances. That said, Strogatz doesn’t shy from the use of an equation or two—or a few more—“How could we visit a gallery without seeing its masterpieces?” he asks. Let’s just say that there are a few places where one might pay a little more or a little less attention depending on the background. But let’s be honest, that’s true of a lot of great books, even some that aren’t about science. Ulysses, anyone?

The inclusion of equations is an interesting stylistic choice and is even something of a gamble from a marketing point of view. Reportedly, Stephen Hawking was told that for every equation he included in A Brief History of Time he would cut his audience in half. He included one and it sold over 10 million copies (if only he had listened). But Strogatz doesn’t just want to tell you about mathematics, he wants to give you a little taste of doing mathematics, and maybe even cure a bad memory or two from high school or college. He’ll help you sum an infinite series or two and even—maybe without you knowing it—show you how to compute an integral. Natural teachers can’t help but want to teach and great teachers can’t help but teach well. It’s not showboating.

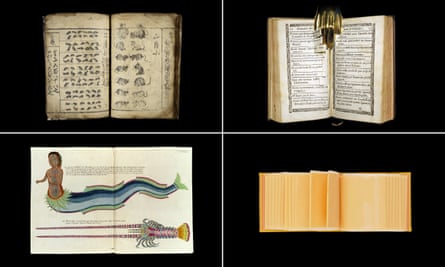

Equations in popular science weren’t always taboo. In 1939 Lance Hogben published Mathematics for the Millions, titled not because it had a target audience of prospective bankers, but rather from its origin tale. Hogben—an unrepentant socialist—was persuaded to write it by “A few friends from the among the million or so intelligent people who have been frightened by mathematics while at school.” Mathematics for the Millions was written with the “conviction that the study of mathematics could be made exciting to ordinary people.” The book is full of equations and even exercises—yes, there is homework—but tempered with historical asides, including philosophical and social commentary. Writing against the backdrop of a looming World War, he unashamedly makes the case for the necessity of a “democratization of mathematics as a decisive step in the advance of civilization.” (One can only wonder if a little math might help address today’s barbarism too.) Of course there are applications: a favorite of mine is Chapter 4, “Euclid without Tears or What Can you do with Geometry.”

Historical anecdotes are a favorite scaffold for popular mathematics (and are now commonplace in textbooks too). Among the many in Infinite Powers, the story of Newton’s discovery of calculus is beautifully retold. Newton loved to calculate! It’s always worth seeing that even geniuses put the time in to do homework. Strogatz’s Infinity Principle does some heavy lifting, but with a light touch, as he explains how Newton used it in concert with his famous Laws of Motion to deduce the elliptical orbit of the planets around the Sun, “Instead of inching the planet forward instant by instant in his mind, he used calculus to thrust it forward by leaps and bounds, as if by magic.” Fast forward a few centuries, and we learn how Katherine Johnson put these ideas to work in the early days of NASA, a story now made famous in the movie (and book) Hidden Figures.

One of the most attractive features of Infinite Powers is that its story of calculus doesn’t end with Newton or even NASA. Some mathematicians might object, but Strogatz has a big-tent view of the subject, seeing it anywhere that the Infinity Principle is at play. “To be an applied mathematician is to be outward looking and intellectually promiscuous. To those in my field, math is not a pristine, hermetically sealed world of theorems and proofs echoing back on themselves. We embrace all kinds of subjects: philosophy, politics, science, history, medicine, all of it. That’s the story I want to tell—the world according to calculus.” He clearly has the “Why should I care?” questioner in mind. and his story of “heroic math” in the discovery of the cocktail approach to treating AIDS is a fascinating and illuminating response to even the most cynical. This is just one of many. Even Churchill would be happy: calculus actually does connect the observing of the Transit of Venus (planetary motion and dynamics) to hearing the marching music accompanying the Lord Mayor’s Show (the mathematics of Fourier analysis).

Luckily—or for some people, mysteriously—mathematics has this great relevance to the real world, sometimes in spite of itself.This “utility proposition” is the one frequently trotted out as the answer to “why should I care about this abstract math?” It’s not only students who hear it; I can promise you that every budget season, the government gets it too. But the real world is a big part of Infinite Powers. The explication of natural phenomena—and with that, the potential as well as reality of exploiting that understanding in terms of product development and even social good makes for a fertile expository wormhole for many a mathematics writer. It gets you quickly to things we do understand—or at least recognize. The ability of mathematics to provide a language that enables useful and predictive descriptions of the world has famously been summarized by Nobel Laureate Eugene Wigner as the “the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics.”

For Wigner the mathematics of symmetry turned out to be crucial to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics—and led to his Nobel Prize. What might be considered unreasonable about it is that the mathematics upon which it was founded wasn’t actually invented with anything about the world in mind. Rather it was created—at least in the beginning—to study a purely internal problem, that of a notion of relatedness among the solutions of equations, which, unreasonably, shares a good deal with a rigorous characterization of the colloquial way in which we think of a human being as right-left “symmetric” or a circle as an object of symmetry. Polynomials, people, and subatomic particles are unified by a pattern of patterns. This is a through-line of mathematics history:

Luckily—or for some people, mysteriously—mathematics has this great relevance to the real world, sometimes in spite of itself. That is, mathematicians don’t always have the solving of the world’s—or science’s—problems in mind when they are doing their work, but lo and behold, surprisingly frequently, ideas borne of aesthetics or intellectual play appear deux ex machina to rescue a theory or enable an invention.

That much of mathematics largely proceeds without the real world in mind is the real mystery to many people. Strogatz tells us, “It can’t just be a trick of circular reasoning. It’s not that we’re stuffing things back into calculus that we already know, and calculus is handing them back to us; calculus tells us things we’ve never seen, never could see, and never will see. In some cases it tells us about things that never existed but could—if only we had the wit to conjure them.” By bringing infinity down to earth (a “quantity passing through infinity”?) and coupling those stories with some periodic excursions back out to the stars, Infinite Powers does a marvelous job of bringing calculus to life. Many of the stories and intuitions will stay with you even after dinner. Whiskey be damned.

*

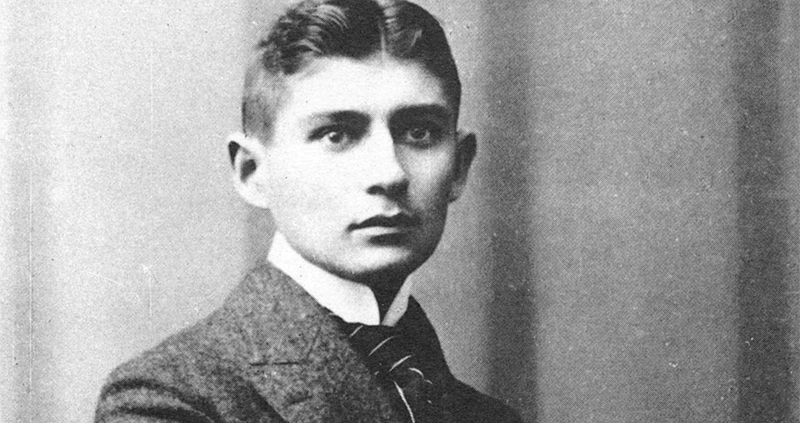

Very different is Karen Olsson’s The Weil Conjectures (FSG). Whereas Infinite Powers follows a more or less linear historical arc, dotted with teachable moments and real world application, Olsson’s book is fugue-like in structure and feel as it interweaves fragments of mathematical history and ideas with a personal story of creative struggle and process, as she tries to triangulate a love of mathematics and a love of words. All of this is hung on a spine of the story of the Weil siblings, Simone—the famed tragic and saintly feminist—and her brother André, one of the great number theorists of the 20th century. Early on in the book Olsson gives the reader a nice preview of what to expect, both in language and content, “If this were a fable, I might begin: Once there were a brother and sister who devoted themselves to the search for truth. A brother who spent his long life solving problems. A sister who died before she could solve the problem of life.”

What we are given is a beautiful and dreamy reconstruction of the Weils’ joined and separate lives, grounded in the facts and quotations of journals, memoirs, and especially, Simone Weil’s well-known copious and dense writings. But, for those in the know, the title of Olsson’s book is also a play on words. Conjectures in the world of mathematics are public and usually very precise guesses about mathematical truths. They are theorems waiting to be proved—or at least that’s what the person posing one thinks. Think, really interesting homework problem that might have a typo. The mathematical Weil Conjectures were posed by André Weil in 1939 and the efforts to prove them—ultimately successful—generated many generations of beautiful mathematics. They concern the mathematics when your number system is finite. The most familiar example of this is the binary arithmetic of computers and digital technology. A zero and one make up their own consistent mathematical world, but similar things happen as long as you work in a number system with a prime number’s worth of numbers.

The mathematical Weil Conjectures make their appearance late in the book. Until then the mathematics moves in and out of the narrative. These take the form of poetic short stories and tangents. They contribute to the tale of the Weils and also to the tale of the teller as she loves, loses, and then returns to mathematics later in life, something of a search for a personal truth and a reconciliation of seemingly divergent creative paths and aspirations. Eventually we learn that the Weil Conjectures embody a proposed connection between the squishy world of shapes that is topology and discrete collections of solutions to equations. Olsson’s goal—or achievement—in her book is not that the mathematical conjecture or ideas are precisely stated, but rather that something of the feeling of doing mathematics and thinking mathematically is communicated. “Think of an ordinary curve, a looping line drawn on a sheet of paper, as a subset of all possible points on the paper. Now generalize the idea to other spaces, other dimensions: conceptual ripples in conceptual dark seas. Think of families of curves and of ways to bundle them together.” Yes, just think of those things. “During the lull between waking and willing, the haphazard miracles of the liminal mind.” Whispers of Churchill.

Among the great pleasures of The Weil Conjectures is its sprinklings of unearthed jewel-like epigrams about mathematics and mathematicians. We learn that Simone Weil wrote, “A mathematician is so rare an animal that he deserves to be preserved, be it only on the score of curiosity.” Olsson grants access to the mind of the mathematician, or rather minds of mathematicians. Creative spirits that choose—or perhaps are compelled—to express their creativity, rare as it may be, in a certain context. For all her poetic protestations to the contrary, Olsson’s is such a mind. She just chose—or was compelled—to do something slightly different with it. We’re all the beneficiaries. Something of a fable, as she takes us from abyss to byss. Tergiversation accomplished.

Hank Willis Thomas, Colonialism and Abstract Art, 2019) (image courtesy the artist)

Hank Willis Thomas, Colonialism and Abstract Art, 2019) (image courtesy the artist)