It all started with a woman and an apple.

In the spring of 1848, Maggie and Kate

Fox were fourteen and eleven, respectively. They were mischievous girls,

prone to boredom and bad headaches, and lived with their parents in the

tiny hamlet of Hydesville, New York. In those days, young women were

urged to cultivate virtues like calmness and prudence, so they’d grow up

not only placid, but healthy: heightened emotions, it was said, could

cause hysterical fits and destroy the complexion. And so Maggie and Kate

invented games to entertain themselves quietly, and indoors.

One night, the sisters discovered that if they dropped an

apple from several feet in the air, or tied a string around it and

dragged it along the floor, the fruit produced a strange sound. A sort

of fleshy clunk. A bump in the night. The type of unidentifiable

noise that creeped their mother out. “A silly woman,” Maggie said

decades later. “She was a fanatic. I call her that because she was

honest. She believed in these things.”

Come nighttime, the girls would play with the apple,

reveling in their mother’s confusion. When the trick became too obvious,

they started rapping on their bedposts, then loudly cracking their

joints. It was silly stuff, but their parents grew more and more

concerned by these mysterious noises, and by the spirit’s—for it must

have been a spirit, they thought—communion with their young daughters.

Before long, Maggie and Kate were conversing with the presence: they

would ask questions, and the spirit would rap a certain number of times

for yes or no, or they would arduously spell out sentences by reciting

the alphabet and waiting for the spirit to rap when they named certain

letters. Neighbors poured into the house to listen, and were shocked

when the spirit seemed to know their personal details; they were even

more shocked when it told them its own story. I am the spirit of a murdered peddler, said the spirit, who claimed to be named Charles, killed years ago by a local man and buried in this very basement!

A few brave men went down to the basement to look for evidence, and

came back horrified—and persuaded—after their shovels turned up bone

fragments and strands of hair.

Forty years later, Maggie and Kate cracked. Their childish

pranks had become a religion that boasted eight million followers. They

were celebrities—and alcoholics, plagued by skeptics, and mentally

exhausted after decades of laboring under the great weight of their con.

Why hadn’t anyone exposed them at the beginning, when they were just

girls? They had found the perfect marks; that’s why: their mother, who

already believed in the supernatural, and their neighbors,

nineteenth-century Americans caught between the material progress of the

present and the folklore of the past. This was an audience that yearned

to retain its connection with deceased relatives—and that wanted to be

entertained.

Of course, it also helped that the girls were

preternaturally clever. Neighbors searched the house high and low, in

those early days, to discover where the mysterious noises were coming

from. They found nothing, not even an apple.

*

In the book of Genesis, Eve is walking

through a beautiful garden when she runs into a trickster in the guise

of a snake, who convinces her to eat an apple and thus ruins the rest of

her life. As time passed, however, Eve and the snake blurred together,

and we now remember Eve as the tricky one. Woman with snake became woman

as snake. Other myths helped calcify the idea. Circe, the Sirens,

Salome, Medusa: devious women slither through history, their names

hissing on our tongues.

Granted, humanity has always adored a trickster. We need

the bracing presence of clever deities—from Anansi to Loki to Mercury—to

undercut traditional power and make us laugh in the process. Down here

on earth, we admire, if grudgingly, the dexterous beauty of legerdemain,

or the charisma of the carnival hawker who deftly parts us from our

lunch money. Con artistry is oddly primal, too; a trickster taps

into our deep-seated need to believe in order and truth and runs away

with it. It stings, yes. But on a purely aesthetic level, we’ve always

been able to appreciate it—so much so that when a stranger with a frank,

honest face manages to bilk us out of a paycheck, chances are we’ll put

him in a movie as soon as we finish licking our wounds.

The idea of a “con” comes from the very thing it shatters: confidence,

which in the fifteenth century was a cheerily communal word (“The

mental attitude of trusting in or relying on a person or thing,”

according to the Oxford English Dictionary), but developed a sinister undertone around 1600 (“Assurance based on insufficient or improper grounds,” also from the OED). In 1849, the year after the Fox sisters began their trickery, a journalist coined the term confidence man

when writing about William Thompson, a bold soul from New York City who

would put on a nice suit, walk up to a wealthy gentleman as though he

knew him, chat for a while, and then ask to borrow his watch while

applying a genius bit of social pressure: “Have you the confidence,”

Thompson would coo, “to trust me with your watch until tomorrow?”

Suddenly, on the spot, with his social graces called into question, the

gentleman would often acquiesce, and Thompson (plus watch) would vanish

into the sunset.

Thompson was betting on the ironclad strength of social

mores—he was predicting, correctly, that people usually behave how they

think they’re supposed to behave. A businessman would consider it

impolite to admit that he didn’t recognize an acquaintance, would think

it rude to cut conversation short, and would feel awkward admitting that

he did not, in fact, trust a peer of seemingly equal stature with his

belongings. Thompson didn’t need a mask in order to steal, because he

operated behind a veneer of masculine power: important-looking papers, a

thick wallet, a fashionable hat, and casual references to classified

business opportunities.

Con women work by the same rules, but

they exploit a different set of expectations. A con woman might not ask

to borrow our watch—or try to sell us the Eiffel Tower, as Victor Lustig

did (twice!) to scrap-metal industrialists in the 1920s, or sweet-talk

her way into the navy as a surgeon, as Ferdinand Waldo Demara did during

the Korean War. The con woman knows she probably wouldn’t be trusted

with such high-stakes professional gambits. But she might convince a man

to propose, provoke him into breaking off the engagement, then sue him.

She might clutch her child and sob, My baby, he’s sick! She

might stop us on the street to intimate that she’s just had a vision,

and lead us inside her shop to consult her crystal ball. Whatever the

specific formulation of her con, chances are she’s exploiting social

assumptions about what women are good for, then reaping a profit.

The Fox sisters took advantage of an

ancient belief: that women—emotional, intuitive, irrational, inward

looking—are innately in touch with the spiritual world. The sisters

aren’t the only ones who’ve exploited this assumption throughout the

centuries: we see versions of the same scam in fake psychics and

fraudulent wellness bloggers. And compared with impostor socialites and

sobbing mothers, a con woman who uses spirituality as her guise is

particularly ambitious. This is because her ask is enormous. The

stranger with the frank, honest face who wants your watch asks nothing

compared with what the spiritual con woman demands from you. Her game is

much bigger: she asks you to believe.

*

The Fox sisters started their tricks with

the apple as an idle diversion from domestic boredom, but the

unexpected attention they received soon led to a career. Within weeks,

their older sister, Leah, apparently realizing there was money to be

made, moved her sisters into a house in Rochester and began charging for

séances. Within two years, all three were legitimate celebrities,

living in New York City and corset deep in the exhausting work of

communing with the dead. When they weren’t conducting séances in

auditoriums before audiences of hundreds, Maggie and Kate were working

eleven- or twelve-hour days packed with group sessions and private

meetings. The movement was termed Spiritualism—essentially, the belief

that the dead can and do communicate with the living, often through

mediums—and as its popularity spread, hundreds of other mediums popped

up across the country, their sessions accompanied by similar rapping

sounds.

On its surface, the séance room was a feminine space:

intimate, private, filled with soft lighting and mystical airs.

Spiritualists asked after their dead children or spouses; politics—like

the growing tensions between the North and the South—mostly stayed

outside. This didn’t mean, however, that these spaces were free from

men. As the Fox sisters grew into beauties, men flocked into their

rooms, eager to sit near them in the darkness, to hold hands around the

table, and to wait for the jolt of a spirit visitation—or the

electricity of a wink from Kate.

For Maggie and Kate, the whole thing was

hell. Not only had their childhood disappeared into the drudgery of

performance, but they now had to endure physically invasive tests from

skeptics. These skeptics—often groups of men—sought to prove that the

sisters’ voluminous dresses weren’t hiding any noise-making props, so

they’d give them specific clothes to wear, or bind the girls’ ankles, or

hold on to their hands and feet to make sure they weren’t moving during

the sessions. Many times, the girls were taken into another room,

stripped down to their underwear, and inspected by women while the men

waited just outside the door. News of the strip search would be printed

in the next day’s paper.

Skeptics weren’t the only ones concerned

with the girls’ bodies. Everyone stared at them. Believers loved to

point to the Fox sisters’ luminous good looks as proof of their

guilelessness: one editor called Maggie’s expression “artless and

innocent” and spoke of Kate’s “earnest simplicity,” while another writer

rhapsodized about Kate’s “pure spiritual face.” Their wide eyes and

girlish bodies made the spirit world seem graspable and nonthreatening

in a way it hadn’t before. “[Maggie] was neither a philosopher of the

divine as Emanuel Swedenborg had been nor a mystic like Andrew Jackson

Davis, who spoke from his own private visions,” writes Barbara Weisberg

in Talking to the Dead: Kate and Maggie Fox and the Rise of Spiritualism.

“Instead… the sounds that followed her—puzzling and stimulating—were as

accessible in their way as she was approachable in hers.”

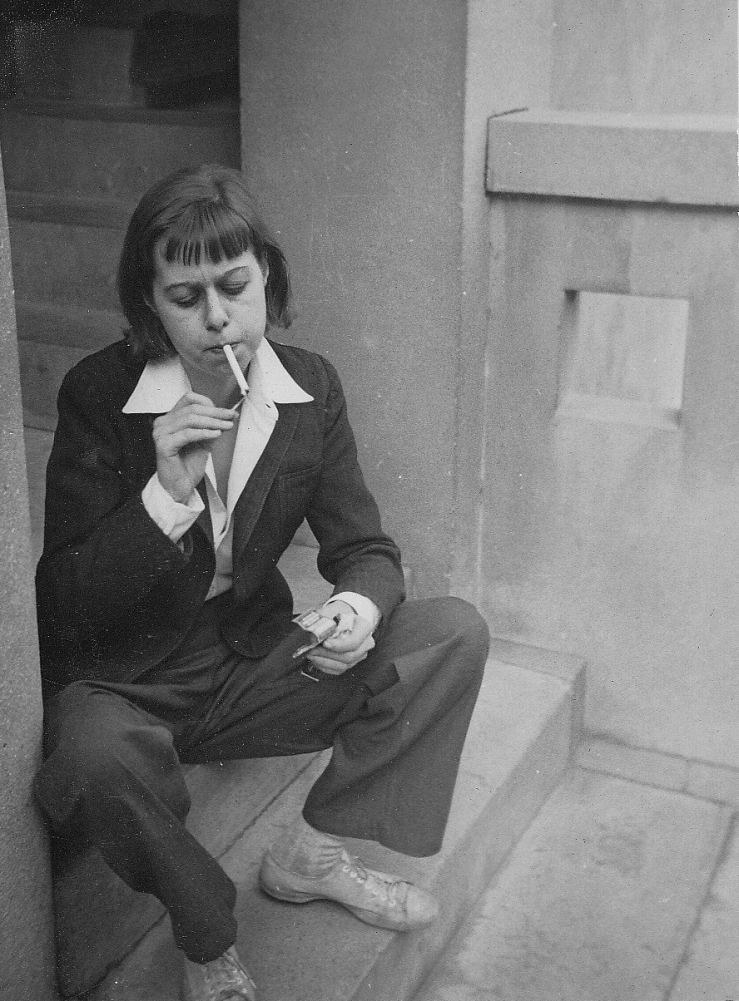

It’s very convenient to look artless and innocent, should

you happen to be a con woman. The con man benefits from an expensive

suit and a jovial expression; the con woman benefits from a pretty dress

and a face of earnest simplicity. None of it is accidental. Whether her

clothes are cheap and disheveled or beautifully tailored, you can bet

your watch that the con woman has planned the effects of her outfit

ahead of time.

*

Bebe Patten was no stranger to the power of a beautiful

dress. Her signature look was angelic: white silk robes and a cross

around her neck. She needed to shine when she was sermonizing onstage.

Bebe’s husband, C. Thomas Patten, didn’t look quite as godly in front of an audience. He joked that the C in his name stood for cash,

and favored cowboy boots, pistachio-colored suits, and ties printed

with dollar signs. In 1944, the two of them crawled into Oakland,

California, with three dollars between them; six years later they had

amassed a fortune of over one million, plus multiple real-estate

investments, a rabidly devoted religious following, and charges of fraud

and embezzlement. The charges, though, were against C. Thomas only.

Bebe remained blameless to the end, her silks spotless, her hands clean,

and her pockets full.

Bebe had grown up in the evangelical

world. As a girl, she’d worked revival campaigns, and she graduated from

a Pentecostal bible college in Los Angeles. She wouldn’t let C. Thomas

sleep with her until they were married, and she wouldn’t marry him

unless he converted to Pentecostal Christianity (or at least that’s the

story they told onstage). It turned out that C. Thomas’s bombastic

nature fit perfectly with the more performative elements of

Pentecostalism. The newlyweds drifted around the South for a while,

preaching here and there, but in Oakland they found the fertile soil

they’d been looking for: “poor people with money,” as Bernard Taper

wrote in The New Yorker in 1959. Their congregants were

mostly folks from the Bible Belt who’d come to Oakland to work at the

shipyards and defense factories, and who found themselves with cash and

an aching desire for community.

The Pattens poured thousands of dollars

into advertising, and began throwing revivals the way Gatsby threw

parties. Their ads, placed in every local paper, promised “Green Palms!

Choir Girls in White! Music! Miracles! Blessings! Healings!” The

revivals would start with prayer and song, led by Bebe, but the

highlight—at least for the Pattens—was the fund-raising. C. Thomas was a

natural showman with no shame whatsoever, and his methods were as

abrasive as they were effective. He would declare that God had just

whispered a specific number in his ear—say, three thousand dollars—which

he and Bebe were now tasked with raising that night. He’d wait a

moment, as though receiving a new transmission from Jehovah, then roar

that two people were supposed to start off the donations by giving one

thousand dollars each. Two people, one thousand dollars each! Who would

it be? He’d badger his audience until two people stepped forward, and

the fund-raising would blaze on. If wallets weren’t opening that night,

C. Thomas would call out names and demand that these people donate, say,

two hundred dollars then and there. As he vacillated between raging and

cajoling, Bebe sat onstage behind him, waiting to give her sermon, with

her eyes on the floor—the picture of a devoted wife.

Their congregants gave and gave,

sometimes ruining themselves in the process. It wasn’t unusual for the

Pattens to raise thousands of dollars in a single night. The money was

for a radio station, they said (they never got an FCC license), or for

an orphanage (they bought a ranch but never brought in orphans), or for a

rest home for “broken-down” ministers (legitimate churches found their

methods appalling), or for Bebe herself (she brought in about four

thousand dollars per month in pure spending money), or for a

“super-auditorium,” which would feature escalators designed to whisk

ailing members of the congregation right up to the altar, where they

could be blessed by the Pattens as they put out their trembling,

liver-spotted hands to… donate more money! On the roof of the

super-auditorium, the couple promised to build a flaming torch, visible

for miles around, as a sign of God’s something-or-other. “COME HOME

QUICK,” one of the choir girls telegraphed her mother. “DAD’S GONE CRAZY

AND IS GIVING ALL HIS MONEY TO THE PATTENS.”

C. Thomas was the archetype of the con

man: flashy, charismatic, supremely confident, and oddly likable despite

his appalling behavior. He was prone to yelling absurdities like “You

fossil faces and stony hearts, you better melt before the Lord if you

know what’s good for you!” Bebe seemed… godlier. She wore a cross around

her neck, after all, not a tie printed with dollar signs. When C.

Thomas was eventually thrown into prison for five counts of grand theft,

charges were never leveled against his partner in crime.

But it was Bebe’s aesthetic that enabled the whole

charade. Without her gloss of spirituality, C. Thomas would have been

nothing more than a loudmouthed sideshow huckster, a joke. With Bebe

onstage—the angel, the woman in white, the one who invited conversion,

the one who embodied transformative spirituality—C. Thomas gained

legitimacy in the eyes of their congregation. He even used her as

leverage: if the congregation wasn’t coughing up enough money, C. Thomas

threatened to cancel Bebe’s sermon.

The Bebe who sat demurely behind her husband was not, of

course, the true Bebe. Bebe the con woman wore silver fox furs and once

hired Greta Garbo’s costume designer to make her a slinky white satin

gown. While C. Thomas stood trial, she preached a cruel sermon about how

anyone who disbelieved them would be damned, all while holding a pink

rose taken from the coffin of a former follower who was “praying in Hell

tonight.” (Like her husband, Bebe enjoyed a good prop.) She prayed

aloud that someone involved in the trial would drop dead: “Lord, smite

just one, to encourage us—just anyone to show us You are on our side.”

In the courtroom, the prosecution was

unmoved by Bebe’s golden cross. “It was she who made the emotional

appeal, she who set the stage upon which he operated,” said the

assistant district attorney Cecil Mosbacher. “They conspired together to

defraud and deceive this community.” But Bebe, cloaked in innocence and

godliness, was never charged with any crime.

*

It’s one thing to take someone’s money. It’s another thing

to take someone’s search for truth and use it to buy yourself Cadillacs

and couture. That’s why it’s amusing to read about diamond heists,

get-rich-quick scams, and swindled aristocrats, but it’s hard to keep

laughing when a young boy gets sucked into a cult, or a bereaved mother

is duped by a psychic, or an impoverished family stakes everything they

have on a fake revival. The Pattens’ cleaning lady sobbed on the witness

stand as she explained that she had given up her life’s savings of

$2,800 after C. Thomas called her “the meanest woman in Oakland” in

front of the entire congregation.

The Fox sisters, too, manipulated the vulnerable. For

months, Kate held private sessions with a thirty-one-year-old widower

named Charles Livermore, who was so distraught after the death of his

wife, Estelle, that a doctor recommended séances to relieve his

suffering.

Kate met with the heartbroken husband every other day. At

first she claimed that Estelle was communicating through her, and wrote

down the spirit’s loving messages for Charles. At their twenty-fourth

sitting, Charles watched in awe as the luminous outline of a woman

appeared in the darkened room. At their forty-third sitting, a glowing,

gauzelike substance rose from the floor, congealed into the shape of a

woman, and walked toward him, closer and closer, until he could see that

it was Estelle herself, visiting him from the afterlife, unable to

speak but reaching out her hand for him to touch it. Charles wrote

rapturously of their meetings in his diary, saying that the spirit was

exactly like his wife and describing how he held her hand, stroked her

long hair, and kissed her on her incandescent mouth.

Was “Estelle” actually Kate, dressed in

gauze that had been dipped in phosphorescent paint? Was the specter

played by an accomplice? Mediums had plenty of ways to make ghosts

appear: by having a naked woman draped in transparent fabric slip out

from behind a curtain, by ducking into a cabinet and reappearing as the

ghost, or by making figures from papier-mâché and bedsheets. In any

case, Charles—desperate, susceptible, and looking for answers—was an

easy mark. He was not there to flip on a light, or yank on Estelle’s

garments, or insist on some more corporeal proof of her presence.

Not everyone was as unguarded as Charles.

Spiritualism was studded with fraudsters like raisins in a fruitcake,

and before long a strange counter-industry emerged to prove that mediums

were fakes. Even the great Houdini joined the anti-Spiritualism

movement, writing a book that debunked famous mediums. As more and more

charlatans were unmasked, the debunking took on a slapstick quality.

During one séance run by a medium named Elsie, a spirit began moving

around the darkened room—until someone flipped on the lights to reveal

that the spirit was actually Elsie herself, dancing under a sheet. In

protest, mediums began hiring bodyguards, called sluggers, who were

ordered to beat up anyone who tried to turn on the lights, yank off the

sheets, or otherwise subvert their magic-making.

It was all kind of hilarious—except for the fact that the

victims believed, wholly. “Were this a mere harmless delusion, one might

be inclined to laugh, or sneer at, and let it die out,” mused one

writer in 1853, “but unhappily, it is producing the most disastrous

effects.” After all, true belief isn’t hilarious at all. It’s private.

It’s vulnerable. And since con artists can sense vulnerability like a

shark senses blood, an awful lot of damage can be done before someone

flips on the light.

*

In the 1990s, an Australian woman who

called herself Jasmuheen caught the eye of the international media

because she seemed to be starting a cult, though Jasmuheen herself

denied the accusation vehemently—she didn’t have followers, she said,

just supporters. Jasmuheen didn’t eat or drink. She was a

breatharian—someone who subsists on “cosmic microfood” in the air—and if

you purchased her book Living on Light: The Source of Nourishment for the New Millennium,

and muscled your way through her twenty-one-day fast, you, too, could

look forward to a life of increased health, energy, sex—and lower

grocery bills.

The initial media coverage took a tone of

amused skepticism. Here was this pretty blond woman with a soothing,

spacey voice, who spouted wacky quotes about how eating was “outdated”

and how her only bowel movements were “rabbit-type droppings every three

weeks.” Her website boasted that “a group of dedicated, tough,

well-trained, self-selected warriors (known as the Knights of Camelot)

have been utilizing themselves as guinea pigs to prove that human beings

do not need food to live.” One journalist wrote an irreverent account

of visiting her mansion and finding that her refrigerator was stocked

with food, that her shelves groaned under the weight of vitamins and

supplements, and that her cutting board was clearly “well-used.”

Unfazed, Jasmuheen claimed it was all for her husband.

Her followers, who numbered several

thousand worldwide, weren’t in on the joke. Though Jasmuheen’s

preachings sounded deranged to the average omnivore, they were intensely

compelling to people in search of spiritual cleansing. If you looked

past the medical unsoundness of her advice, you started hearing a

message that said: Here is a way for you to be freed from the messiness

of living in a human body. Here is a way to be better. To be purer. To

find your “personal paradise,” as Jasmuheen would say. This way is

simple: line yourself up with the universe, take one last look at the

chips and fries and sodas and salads and teas and cakes and cookies, and

just… stop.

Before long, the deaths began. In 1997, a

thirty-one-year-old kindergarten teacher from Munich named Timo Degen

survived twelve days of Jasmuheen’s fast, then fell into a coma, and

soon died. (A hospital spokesperson said that he looked like “he’d been

in a concentration camp.”) The next year, a fifty-three-year-old

Australian woman named Lani Morris attempted the fast; after losing her

ability to speak and vomiting black liquid, she died of dehydration,

pneumonia, kidney failure, and severe stroke. One year later, the body

of an Australian woman named Verity Linn was found half naked and curled

in the fetal position in a lonely part of the Scottish Highlands. In

the pitiful pile of her possessions lay a diary that spoke of her

resolution to be “spiritually cleansed” before the year 2000. Next to it

was a copy of Jasmuheen’s book.

This was enough to get the spotlight

turned on Jasmuheen in a different way. “Blonde, thin and dangerous,”

one article called her. The media now demanded that she prove she didn’t

eat, and Jasmuheen calmly agreed to be tested. The plan was that the

Australian TV show 60 Minutes would lock her in a hotel room, film her around the clock for seven days, and have a doctor present to monitor her progress.

“It’s not about starvation and it’s not about fasting,”

Jasmuheen told a reporter before the test started. “It’s about matching

frequencies with this divine force that drives every breath.”

When he responded, “Well, going without food involves

starving yourself,” she didn’t miss a beat: “Depending on your

experience,” she said.

*

The act of revealing a con artist might seem satisfyingly

cinematic, but the moment of revelation is often deflating. Spiritual

cons thrive in low-visibility conditions: candles, half-closed eyes, an

atmosphere conducive to a sense of being transported. But in the cold,

hard light of day, it’s all terribly banal. The Wizard of Oz knew what

he was talking about when he told us to pay no attention to the man

behind the curtain.

On the air, Jasmuheen’s vague

proselytizing was suddenly confronted by the impassive test of modern

medicine. By day four, her claims that she was feeling fantastic were

debunked by a list of statistics to the contrary: her heart rate had

doubled, her blood pressure was down, she’d lost about thirteen pounds,

and her speech was slurred. If she continued, the doctor said, she

risked kidney failure. Afraid that she’d die on its watch, 60 Minutes

stopped filming. Jasmuheen quickly sent out a press release: “What

appears to be delusion to some is simply a preferable reality to others,

for without our dreams and visions, humanity has no hope.”

Miraculously, the Fox sisters had long avoided precisely

the sort of embarrassment that Jasmuheen was dealing with, despite

constant attempts to disprove their connection to the dead. And then

something changed. After decades of dodging skeptics, Maggie and Kate

suddenly chose to reveal themselves.

By the time they reached their fifties, the sisters were

sick of Spiritualism. Despite their fame, professional success, and mobs

of adoring believers, life had not been kind to either of them. They

were both widows and heavy drinkers, furious at their overbearing

sister, Leah, for the way she’d pushed them into the spotlight—and

plagued by guilt. Before each séance, Maggie would mutter, “You are

driving me into Hell.”

In the fall of 1888, Maggie appeared at

the New York Academy of Music to give a speech. Kate sat in the

audience, nodding along. Maggie began: “I do this because I consider it

my duty, a sacred thing, a holy mission, to expose it. I want to see the

day when it is entirely done away with. After I expose it I hope

Spiritualism will be given a death blow. I was the first in the field

and I have a right to expose it.”

She

told the audience about the apple trick and her gullible mother. She

said that when her mother called in the neighbors to listen to the

sounds, she and Kate realized they could produce an even spookier effect

by discreetly cracking their toes.

She

told the audience about the apple trick and her gullible mother. She

said that when her mother called in the neighbors to listen to the

sounds, she and Kate realized they could produce an even spookier effect

by discreetly cracking their toes.

“Like most perplexing things when made

clear, it is astonishing how easily it is done,” said Maggie. “The

rappings are simply the result of a perfect control of the muscles of

the leg below the knee, which govern the tendons of the foot and allow

action of the toe and ankle bones that is not commonly known. Such

perfect control is only possible when a child is taken at an early age

and carefully and continually taught to practice the muscles which grow

stiff in later years.”

Maggie lifted up her skirts, took off her shoes, and

allowed three doctors to join her onstage and hold on to her big toes.

“Everybody in the great audience knew that they were looking upon the

woman who is principally responsible for Spiritualism, its founder, high

priestess, and demonstrator,” The New York Herald reported.

“As she remained motionless, loud, distinct rappings were heard, now in

the flies, now behind the scenes, now in the gallery.”

The absurdity of the scene wasn’t lost on journalists, who

called it “ludicrous,” and the sight of three men touching a woman’s

foot would have been vaguely suggestive for the audience. Still, there

was a somber power to the bizarre tableau. There stood a woman who had

weathered attempts at exposure for decades, hiking up her skirts and

doing it herself.

Bebe Patten was spared all such

humiliations. After C. Thomas’s death, in 1958, she scrubbed her

reputation until it gleamed, and she never looked back. Her obituary,

which doesn’t mention C. Thomas, speaks of her “76 years of Christian

ministry as evangelist, pastor, teacher, broadcaster, editor, and

founder and leader of institutions.” In a photo taken when she was an

old woman, Bebe holds a Bible open over a lush bouquet of red roses,

with a cross around her neck. Light hits her hair from above.

*

“What I find very, very difficult, is

whether you believe this gibberish, and are therefore in need of some

help, or whether you don’t believe it, and you just put it forward, and

it makes you a fraudster,” the reporter from 60 Minutes said to Jasmuheen.

She responded, “Don’t you think you should leave it to the audience to decide?”

It’s a safe answer: the con woman knows that her audience

will never reveal her. They’re already in too deep. Each one is a

perfect mark, full of contradictions, questions, and doubts. And each

one has already played their hand simply by showing up—all the con woman

needs to do is wait for the impressionable believer to walk through her

door.

Still, the con woman herself is not invulnerable to

belief. A month before denouncing Spiritualism from the stage, Maggie

Fox told a journalist that she’d tried hard to believe in spirits—and

failed. “Why, I have explored the unknown as far as human will can,” she

said. “I have gone to the dead so that I might get from them some

little token. Nothing came of it—nothing, nothing.”

It’s tempting to see the con woman as

pure, slick surface—a fantasy of feminine swagger. A fearless woman,

seemingly innocent but deliciously amoral. Troubled by no gods. Haunted

by no ghosts. Of course that, too, is just a trick.

All contents copyright 2003-2019 The Believer and its contributors. All rights reserved.

IV. STUDIO

IV. STUDIO

She

told the audience about the apple trick and her gullible mother. She

said that when her mother called in the neighbors to listen to the

sounds, she and Kate realized they could produce an even spookier effect

by discreetly cracking their toes.

She

told the audience about the apple trick and her gullible mother. She

said that when her mother called in the neighbors to listen to the

sounds, she and Kate realized they could produce an even spookier effect

by discreetly cracking their toes.