Ce texte de Tom Tykwer (remarquable, essentiel) fut publié initialement dans le Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung daté du 8 février 2007. Tykwer l’avait rédigé à l’occasion de la première berlinoise de Berlin Alexanderplatz

(qui venait d’être restauré). Il affirma qu’il s’agissait d’un hommage

au film et d’« une déclaration d’amour au cinéma expérimental ». La

traduction anglaise que voici a été réalisée par Stephen Locke pour

Criterion Collection, qui offrit au public américain une superbe édition

du film en coffret de DVD/BD.

[Merci au FAZ et à Criterion. Mais je n’ai pas trouvé de version française, désolé, Ch.T.]

~~~

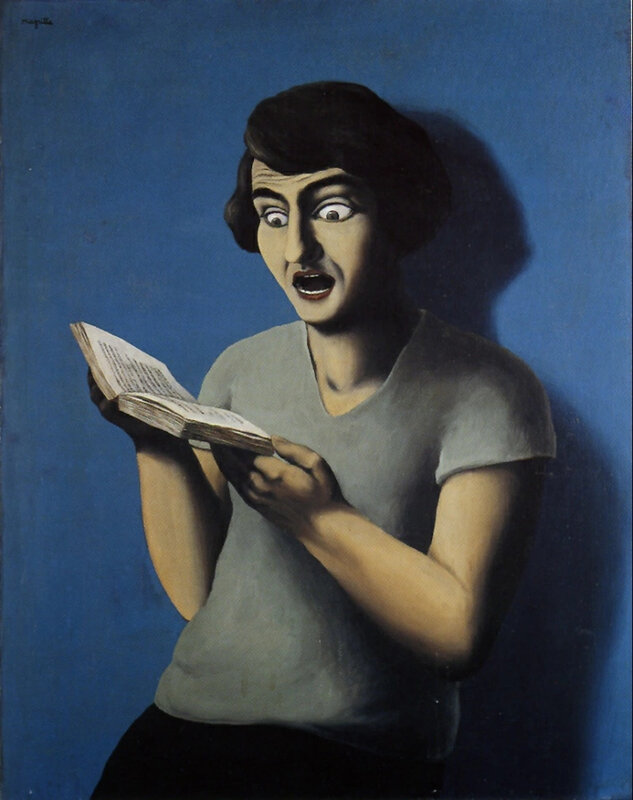

I The Anti-Television Film

« To

listen to this, and to meditate on it, will be of benefit to many who,

like Franz Biberkopf, live in a human skin, and, like this Franz

Biberkopf, ask more of life than a piece of bread and butter. » Alfred Döblin, from the preface to Berlin Alexanderplatz

It is once again time to think, to

speak, and to write about this fifteen-hour film, which, at the onset of

the eighties (that decade that would later bring with it an end to the

cold war and a comeback for capital), enraged the national spirit and

occasioned assaults by the yellow press and (in the wake of this)

protests from "millions of television viewers" who felt themselves

"robbed of their subscription fees" (Bild newspaper).

The public protest against this work,

which everyone who was in the vicinity of Germany at the time remembers –

and many remember the outrage even better than the film itself – was

directed against the television stations, the filmmakers, the ensemble,

and naturally, above all, against the director, Rainer Werner

Fassbinder. Although the film’s alleged unacceptability in technical

matters (it was accused of considerable flaws in image and sound

quality) was thrust into the center of attention, these problems, it

appeared, were hardly worthy of such a storm of indignation. The pain

caused by the film somehow went deeper, and with each further episode,

broadcast one week after the other, it seemed like a dirty thorn was

boring itself deeper and deeper into the wound of this republic, a

country that wasn’t very comfortable in its own skin anyway and,

accordingly, was soon thereafter to fall into a cultural and political

stupor (Fassbinder died in 1982; Kohl became chancellor). At the time,

Germany had no desire at all for the celebrated excesses of this film,

its prancing obscenity and unshrinking crassness, a kind of German swan

song, and all the more so since all these elements meandered – freely

floating and without commentary, always asking but never answering, in

other words completely ignoring the brief for public edification vested

in public television – over a period of thirteen long television weeks.

If you take into account the almost

unlimited freedom – despite, for that time, the considerable expense of

the production – with which Fassbinder was able to realize this

extremely introspective, almost inaccessible film concept, it sheds

light on the exceptional position he enjoyed as a filmmaker then. Just

having turned thirty-four years of age, he already had some forty films

under his belt, including his latest and greatest box-office triumph, The Marriage of Maria Braun. Nowhere in Berlin Alexanderplatz does

one get the feeling that he is holding back or censoring himself; it is

one of those films, perhaps like only Jacques Rivette’s Out 1,

that completely turns its back on traditional, economical narrative

conventions – and that at the same time, seemingly paradoxically, feels

bound to the narrative, coming back to it time and time again, sometimes

even in a compulsively conservative way, only to undermine it right

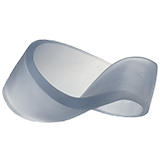

away for the sheer delight of it. It is a film that plunges directly

into its topic, a story straight out of everyday life, tears it piece by

piece away from its concrete, reality-oriented style, and, with an

extremely intimate, almost private view, dissects it, stretches it, and

then, above all, spins it out into time, expands it, as it were, to such

a degree that interim spaces are torn open in this drawn-out time; and

Fassbinder wants to gaze down into the fissures in this vastly

stretched-out time, to rip them even farther apart, to look even deeper,

until time itself seems no longer expansible – and then splits

completely asunder.

What follows this is merely an epilogue, a final chord in the midst of the Black Hole of this temporal rift.

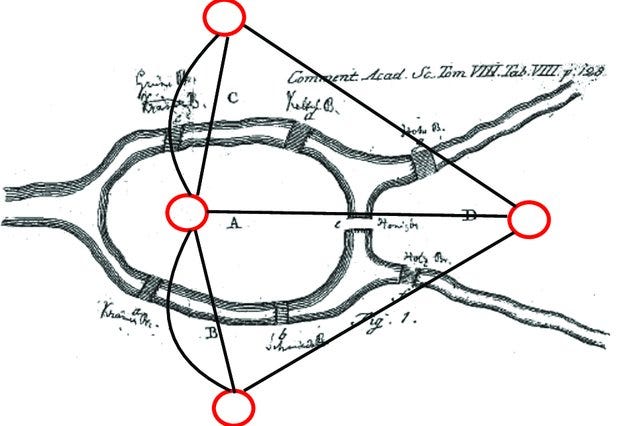

In other words, Berlin Alexanderplatz, this

thirteen-part film plus the said "epilogue", was never really a TV

movie. It is a narrative experimental film that, juggling various

theatrical principles, seeks a hideaway between the traditional and the

avant-garde.

Concerning the visual aspect, Fassbinder

and his cameraman, Xaver Schwarzenberger, appear to have been flouting

the medium of television here as well: their joint disdain for the alarm

signal on the camera’s light meter as it no doubt wildly lashed out

seems otherwise too provocative. As a result, the night shots, which

were obviously composed for the big screen and a sensitive film

emulsion, were watered down into a faint, flat, gray-black blur on most

of the German Telefunken TV sets available at the time.

From then on the film seemed ostracized

as "unbroadcastable", even "unshowable", but resistance arose on the

part of some festivals and individual movie theaters, and, long after

Fassbinder’s death, a few increasingly scratched 16 mm prints began

touring through the art houses and film museums of the world — until

these prints, too, were no longer watchable.

Now, Juliane Lorenz, with her Fassbinder

Foundation, has been able to convince a number of cultural and film

subsidies, as well as technical film companies, to undertake, under

Schwarzenberger’s direction, the painstaking restoration of the negative

of the film – originally shot on 16 mm and blown up to 35 mm – and

above all to dare to make a new optical and color correction, which, in

view of the technology now available, appeared to be a very promising

undertaking. And in fact the legendary "darkness problem" has more or

less disappeared; except for a few shots, it was possible to bring out

the contrasts in the monochrome night compositions to such a degree that

there is always an intelligible picture and not just a picture puzzle.

Never before have the filigree compositional stylistics of Berlin Alexanderplatz been

seen – one could hardly even have imagined them – in this form. At the

same time, Schwarzenberger has taken care not to lose the quality of

this intimate night spectacle, precisely because the choking confinement

evoked by the slightly soft-focused darkness of the images reflects the

narrowness of a world that is constantly threatening to crush Franz

Biberkopf.

II The Story

« You have to hear stories. It is pleasant and sometimes even makes one better. » From Mahabharata, an Indian epic

Franz

Biberkopf (Günter Lamprecht) is let out of prison after having served a

four-year sentence for the manslaughter of his lover. He is spit out

into the raw, increasingly impoverished city of Berlin in the late

twenties and tries to get a foothold again, an ongoing effort at which

he is seldom able to prevail. He gets to know a number of women with

whom he spends a short time, or sometimes a bit longer, but it is only

when he encounters Mieze (Barbara Sukowa) that he believes he has found

the right one. He has a few close or looser friendships with various

men, among them Reinhold (Gottfried John). The feelings between Franz

and Reinhold are stronger than they are able to fathom, and thus this

involvement develops a momentum of its own that finally leads to Franz’s

undoing.

At the beginning of the story, Franz

swears to "become an honest soul", but fate is not on his side, and he

suffers setback after setback, until one finally gets to him with such

force that it breaks his iron will, and in the end, robbed of all hope

for a piece of happiness, he is left alone and broken.

III Not the Story

« So the crucial part of Berlin Alexanderplatz

isn’t the story; this is something the novel has in common with some

other great novels in world literature; its structure is, if possible,

even more ludicrous than that of Goethe’s Elective Affinities —

the essential part is simply the way in which this incredibly banal and

unbelievable plot is narrated. And the attitude toward the characters,

whom the author exposes in all their dreariness to the reader, while on

the other hand he teaches the reader to see these characters, reduced to

mediocrity, with the greatest tenderness, and to love them in the

end. » R.W. Fassbinder, 1980

The story, in other words – normally the

Holy Grail of every screenwriter and filmmaker – is not the point. With

this Fassbinder establishes a method that marks Berlin Alexanderplatz

to a greater degree than any of his other works. While almost stoically

ignoring all the demands of a plot, he sets out to circle around

singular human conditions, to penetrate them, and to bring forth a

reflexive (referring back to the subject) truthfulness that shows that

nothing is more foreign to a person than himself and that he is

therefore constantly in search of himself. And therefore the voice-over

commentaries, spoken by Fassbinder, never serve as parentheses or

interlinkings of plot elements; they lack, in fact, all

narrative-binding impulse. Rather, they draw closer attention to moments

in which something entirely individual comes to the fore or in which a

thought or a feeling by or about a person is brought to a halt,

prolonged, or protracted. What Fassbinder recounts are passages from the

novel that reveal that it, too, is strewn with unconventional, prosaic

digressions that constantly, by means of facts, associations, and

rebounding fragments of an idea, demonstrate the disjunction of the

narration.

The gist of the identificatory conception of Berlin Alexanderplatz

is that in the beginning the protagonist appears as a rather

simpleminded, coarse soul; but as the narrative progresses we soon

recognize that our assessment is in no way adequate to account for the

complex, deep sensibilities with which Franz Biberkopf comes to grapple.

Which doesn’t mean that Biberkopf is not, in fact, simpleminded and

coarse – but rather that we must nevertheless concede to him "such a

differentiated subconscious, combined with an almost unbelievable

imagination and capacity for suffering, that one would have to look long

and hard for [its] equal in world literature" (Fassbinder).

IV Repetition and Expansion

« Cinema

is there to show us what we would not see without cinema. To expand the

word and the image. To make visible what is normally invisible. » Jean-Claude Carrière, in The Secret Language of Film

By

repeating, prolonging, or stretching out events, Fassbinder is seeking

something that he assumes is to be found in the ritualistic gestures of

human behavior, in our tendency to make a rule out of things, to repeat

them, to find the way to an inner order through outward order, creating

an organized course of events, until these finally strike us as

compulsory.

Seen in this light, Fassbinder is an

epigone of Pina Bausch and a precursor of Christoph Marthaler, two

theater people who through the repetition and prolongation of social

gestures reveal people’s addictive potential for self-destruction,

culminating in the ritualistic.

One of the strange things about the experience one has viewing Berlin Alexanderplatz is

that the stretched-out temporality does not leave the impression of

making the story more precise, but rather creates an elliptical

sensation. For a while your concentration is so completely distracted

from the narrative chain of cause and effect that you almost lose your

orientation and ask yourself, in view of such a total standstill,

whether the story will ever get moving again. In the fascinating part 4,

above all, it plods along like almost no other film has, except perhaps

Bruno Dumont’s recent Twentynine Palms. Or maybe like in the first act of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal.

V Structural Folk Theater

« What we once again appreciate in Young Werther,

even though it sometimes almost makes us mad [...] is precisely the

inappropriate, even exotic alliance of the natural with the artificial,

which brings to light a truth that is not too far away from that of

theater. » Thierry Jousse on Jacques Doillon, in Autorenkino und Filmschauspiel, by Anja Streiter

Jacques Doillon, the director of such films as Young Werther and The Pirate,

is another next of kin of Fassbinder’s, an auteur who rips situations

out of their so-called authenticity in order to search for their meaning

on an alternative, artificial field of play. For Fassbinder it is

extremely important that with all his prolongings and repetitions he is

not only working through some formal experiment but is at the same time

exploring the figures themselves as soon as they climb onto the hamster

wheel and satisfy truly human needs, both sublime and primitive. But for

all the choreography, his characters are not just at the mercy of some

directorial tick, not just puppetlike shells as with Robert Wilson, for

example, but rather they act out and live through these sequences as

psychological beings, as three-dimensional individuals.

In

the ritualized romantic rondel that unfolds between Mieze and Franz,

for example, the desire for the infantile, brotherly-sisterly, escapist

pleasure of togetherness formulates itself for both characters to an

exaggerated degree that only naively innocent lovers are capable of

celebrating – which, actually, should be familiar to everyone, since

after all, every love is innocent. To cite another example of a

different nature: the seemingly infinitely repeated, traumatic murder of

Ida by Biberkopf expresses the accidentalness with which vehement rage

can suddenly turn into bloody madness, and feels at the same time

somehow unreal, like a remote-controlled danse macabre.

At

least this is the way the actors play it. And they don’t play it with

even the slightest bit of detached nuance. On the contrary, the acting

style that marks Berlin Alexanderplatz is (not always,

but often) earthy, extroverted, sometimes even declamatory—and thus

obviously indebted to folk theater, alternating by choice between

burlesque and dramatic sketch. That kind of folk-theatrical gesture,

which already suggests itself in the dialect from the novel, was used by

Fassbinder in many of his works as an instrument of stylization. Folk

theater, historically defined through its distinction from court

theater, had stamped its mark on the director just as much as had the

avant-garde stages of the late sixties, and his very own personal style,

which grew out of a fusion of these two influences, was taken to the

extreme and to perfection in Berlin Alexanderplatz.

VI Biberkopf and Other Men

« As

director it could also be possible, of course, to show particular

consideration to the leading actor, in so far as the director shouldn’t

drive him crazy with other things, since he has such a difficult task to

perform [....] In fact, the only source of disturbance I had was my

director, who continually interfered in my work. » Günter Lamprecht, 1981

Nonetheless,

or maybe because of it, Günter Lamprecht as Franz Biberkopf – and this

can be stated unconditionally – was perfect casting for this film. And

even if Lamprecht might have quarreled with Fassbinder so much, he did

in fact delve down deeply into Fassbinder’s cosmos, adapt himself

congenially to the elegiac fragment of a screenplay, and give just as

much energy and variation to each subtle individual moment as to the

blaring pamphleteering. Lamprecht’s Biberkopf is (probably like the

director as well) a fragile berserker for whom the world has proved too

narrow, the heart too big, the passion too oppressive, and the intellect

too weak, and who lets himself fall, eyes wide open, but with limited

knowledge, into the shredding machine of human fate.

With

a tour de force performance as varied as it is graphic, as loud as it

is gentle, Lamprecht is a huge, violent child in the body of a man – and

thus all of the thematic threads of the film logically come together in

his character.

Everything

this man goes through in his tortured life turns his (erroneous and

roundabout) fateful course into a kind of Passion, and as if this

perfect fool were a preacher in disguise, apostles are hanging at his

heels. They are called Nachum (Peter Kollek), Meck (Franz Buchrieser),

Lüders (Hark Bohm), Baumann (Gerhard Zwerenz), and Reinhold – and they

all use him, either as psychic membrane for their neuroses, as patient

for their promises of salvation, or as willing victim for their

exploitative intentions. For Biberkopf’s perfect foolishness is both a

provocation and a promise for all the fallen angels around him: they

hope for redemption at his side, as if his simplicity could heal their

neuroses, their despair, and their impairments. But Biberkopf is not all

that simple after all, and he has no desire to be membrane or patient

or victim, and this makes the whole thing complicated.

VII Reinhold and Other Women

« [This

is] by no means a question of something sexual between two people of

the same gender; Franz Biberkopf and Reinhold are in no way homosexual

[...] No, what exists between Franz and Reinhold is nothing more nor

less than a pure love. » R.W. Fassbinder, 1980

The

most important person in Biberkopf’s life is not called Mieze nor Eva

(Hanna Schygulla) nor Lina (Elisabeth Trissenaar) but rather Reinhold,

and is in fact a man. A deadly radiant energy emanates from this

friendship, a magnetism that has fatal consequences for both of them and

that in the more than ten hours in which Reinhold is present in the

film is never entirely understandable, but rather remains unexplained to

the end. It is simply that Franz loves Reinhold, no matter how much

Reinhold takes it out on him, and Reinhold no doubt loves Franz, too,

and it’s too much for him. This therefore brings about a destructive

downward spiral, at the end of which, in an endless single take,

Reinhold’s attempt to seduce Mieze leads to her murder.

By

contrast, the women in Biberkopf’s life rule his everyday routine, they

are the signature figures (and bear the wounds) of the various periods

of his life, they take each other’s place like relay runners and, with

the exception of Eva, are easily seduced. But then love gets in their

way. Biberkopf gives each of them his affection and protection but not

his heart. This is first captured by Mieze, who seems almost related to

him in her childlike, cheerful nature. Franz can mirror himself naively

in Mieze, and the two of them soon behave together with confidential

playfulness, like Cocteau’s "enfants terribles". And if it weren’t for

Reinhold, Franz might have found happiness with Mieze.

VIII Rainer Werner Biberkopf

« My

life would have turned out differently, certainly not as a whole, but

in some respects, in many, perhaps more crucial respects than I can even

say at this point, differently from the way it turned out with Döblin’s

Berlin Alexanderplatz embedded in my mind, my flesh, my body as a whole, and my soul – go ahead and smile. » R.W. Fassbinder, 1980

Certainly

almost everyone who occasionally or more often reads a book can name

their favorite hero or heroine, a literary figure onto which their

identity-seeking projections are directed, prose characters to which

they feel related or in which they even find themselves embodied, and

their own insular life therefore seems less lonely and a bit protected.

That this literary character for Fassbinder was Franz Biberkopf is obvious; elements or direct quotations from Berlin Alexanderplatz show

up time and again in his earlier films, and the Döblinesque view of

destructive yet yearning, sensitive men appears like a blueprint for

tragic heroes throughout Fassbinder’s oeuvre. It is, of course, at the

same time a direct reflection of Fassbinder’s own emotionally chaotic

life, with all its complicated polygamous bonding dynamics. The most

conspicuous predrafts of a Biberkopf figure can probably be found in In a Year of 13 Moons (1978) and Fox and His Friends (his somewhat underrated masterpiece from 1975, where the figure played by Fassbinder himself is even called Franz Biberkopf).

« And

indeed, what would a person raised just like us, or similarly, see in a

love that doesn’t lead to any visible results, to anything that can be

displayed, exploited, and thus made useful ? » R.W.Fassbinder, 1980

Franz’s

love of Reinhold is a mystery not only to himself but also to us – and

yet we know what he’s talking about. The film touches here on a

collective secret knowledge that, rumbling in our subconscious, brings

to mind on some strange evening of our life a confusing feeling of

deepest tenderness for a person we never really thought played an

important role in our life.

IX Legato/Staccato

« Good close-ups have a lyrical effect. They were ‘seen’ not by the good eye but by the good heart. » Béla Balázs

Berlin Alexanderplatz is

for considerable stretches a film of long takes, uninterrupted sequence

shots, sometimes for minutes without a cut, which means that the cut

takes place in the camera, as it were, by moving the camera position

with the dolly and changing the frame by zooming. The close-up, for

example, is often used not as a response to a long shot or as a

follow-up to a countershot but rather as something sought out by the

camera, which glides silently up to the figures – above all Biberkopf –

who dance toward their marked positions, as in slow motion, until

finally lens and object come together.

The

target reached is often an image of limitation, because Xaver

Schwarzenberger’s camera again and again finds window frames, gratings,

or wooden beams that narrow the framing of the picture like a

passe-partout, a frame within a frame that clamps in and firmly holds

the personnel like prisoners of an image. Or like the ever-present

parakeet in the birdcage.

But

at some point in every long take the cut has to come, and every time it

must have been a great challenge to find the exact right moment for it,

sometimes as a break, sometimes in a state of flux, and there are times

when the image simply vanishes into a fade-out.

Then,

time and again, especially in the epilogue, editor Juliane Lorenz

counteracts this method with quick, aggressive stretches of associative

montage, and out of the contrast of these dynamic poles arises the

unnerving rhythm of the film, which, underscored ubiquitously and with

evocative insistence by Peer Raben’s music, swings unpredictably and

erratically to and fro between elegy and adrenaline – which is an

attempt on the one hand to do justice to Biberkopf’s subjectively

varying perception of time, and on the other to capture the delirious

energy of Döblin’s prose.

X Laughter in the Dark

« Not by wrath does one kill but by laughter. » Friedrich Nietzsche

And this Biberkopf does himself.

In

the laughter that sometimes bursts forth out of Biberkopf like a

machine-gun salvo and then seems never to stop, distorting his face into

a grimace and revealing him as someone who overcomes his failure with

the booming gesture of a winner – in this laughter that is never a pure

light laugh but always a bellowed, demanded, longed-for burst – herein

is Biberkopf’s fear laid bare. Laughter is Franz’s weapon to keep panic,

doubt, and worry in check.

In

the end, the laugh turns into a cry, the never-ending cry of a man whom

life does not want to deliver from his guilt, his innocence, his

offense.

Epilogue

We don’t understand him, this Biberkopf, and yet we know what he does, and we suspect why. That is the viewer’s dilemma in Berlin Alexanderplatz:

we know what to make of it but then again we don’t, and we are

sometimes angry to be left so alone by a film that doesn’t want to help

us decipher Franz Biberkopf and his emotions but that succeeds at the

same time by dispensing with all interpretative aids and instead

insisting on observation in order to create a close rapport with the

figure. A rapport that is exceptional even for Fassbinder’s cinema.

The

way we see films and how they have an effect on us changes over the

years, just as one changes as a person; this is an impression familiar

to everyone. In the past I had no trouble at all sitting in the movies

for days on end, watching one film after the other, with no qualms about

jumping among genres, from Tarkovsky to Spielberg, from Bergman to

Hitchcock. There was a seemingly endless reservoir of time and patience,

and I felt an ever-playful openness; it was never too much for me. The

emotions had their effect and then spread out rather diffusely and

without reflection in the cosmos of memory.

When I watch a film today, however – even an admittedly exceptional one, like United 93 – or,

for that matter, simply stick it out to the end, then it seems to me

completely impossible, even physically, to move along without a break to

the next cinematographic impression, to slip smoothly into another

story, another rhythm, another atmosphere, and the realm of impressions

that develop out of it. In other words, the half-life of an intensive

filmic experience has slowed down appreciably, or else a film finds,

potentially, a greater echo in one’s own history, in the personal zones

of resonance in the memory.

So

I sit there after an emotionally intensive film and vibrate. Then I

need time, and also to talk about it, in order to digest what I have

virtually experienced.

I saw the fifteen-hour Berlin Alexanderplatz Remastered – twenty-six

years after the first time – in January 2007 over two days in a small,

cozy theater. I was very excited and looked forward to the demanding and

yet luxurious task of writing an exclusive text after attending an

exclusive screening. And I must admit that for some stretch of the time

it was surprisingly hard work.

The

film is not only long but, above all, as was laid out earlier, is

committed to a narrative method that on the one hand repulses the

viewer, while on the other aims to swallow him up, drawing him into the

decelerated, asthmatic environment of its story. I almost want to say

that you are held down underwater and, gasping for breath, look at the

shimmering reflections on the surface, but from below. They are

beautiful, these reflections, but if you want to look at them more

closely, the film pulls you down deeper underwater. The pressure

increases, and you are afraid of suffocating. That might sound

fascinating, and after all it is an amazing film that can generate this

feeling – but I wouldn’t be telling the truth if I didn’t admit that the

whole procedure demanded an enormous amount of patience, curiosity,

perseverance, and density of feeling.

If

one considers once again the importance Döblin’s novel had for

Fassbinder’s development and his attempt to come to terms with Germany

and the Germans, it seems almost inevitable that this mammoth film

adaptation would rank as a key work in his oeuvre. And yet the film will

not let itself be forced into the idea of the sum of all parts, will

not be the coherent focal point among all the other parts of his life’s

puzzle. Berlin Alexanderplatz is, still today, a visual,

conceptual, and emotional megaquarry, a sometimes unfocused, often even

chaotic, but also constantly fascinating excess consisting of violence,

passion, contempt, desire, and, yes, somehow also love, a film in which

people scream, laugh, cry, and screw outrageously and which never

entirely comes together as a whole, never wants to come together, a film

that has no desire at all to be packed away into a well-formulated

crate in order to sit on the shelf as a key work, deciphered or not.

What is left of Berlin Alexanderplatz, this endless canon of the sublime and the trivial, is thus a perpetuum mobile of the human dance of love and death.

To

examine and to listen to all this in its very impertinence and

truthfulness and beauty and hideousness will be of benefit to many who,

like Franz Biberkopf, live in a human skin and who share a feeling with

the author of this text, namely the desire to ask more of cinema than

merely a story.

Tom Tykwer, 2007