Leibniz’s Mathematical Approach to God

We

know that Kurt Gödel (1906–1978) worked intensively with Leibniz

(1646–1716) towards the end of his life. Gödel’s obsession with Leibniz

had reached such a degree that, according to Gödel, when some people had

destroyed some of Leibniz’s writings, and Menger asked Gödel, “Who could have an interest in destroying Leibniz’s writings?”, Gödel would say, “Naturally, those people who do not want men to become more intelligent!”

(Menger, 1994). When his friends advised him to focus on his studies,

rather than studying and reading Leibniz’s works, he would not pay

attention to them. Eventually, the expected happened, and Gödel

continued to follow Leibniz’s footsteps and gave God’s ontological proof

like Leibniz.

In this article, I will refer to Leibniz’s work and interpretations, such as his characteristica Universalis

and the binary number system, to give the reader an idea of the part

of his work, particularly about mathematical philosophy. I will also

explain how Leibniz understood the concepts of proof and analytics.

Finally, I will focus on Leibniz’s role in mathematics within the

framework of theology and metaphysics/philosophy.

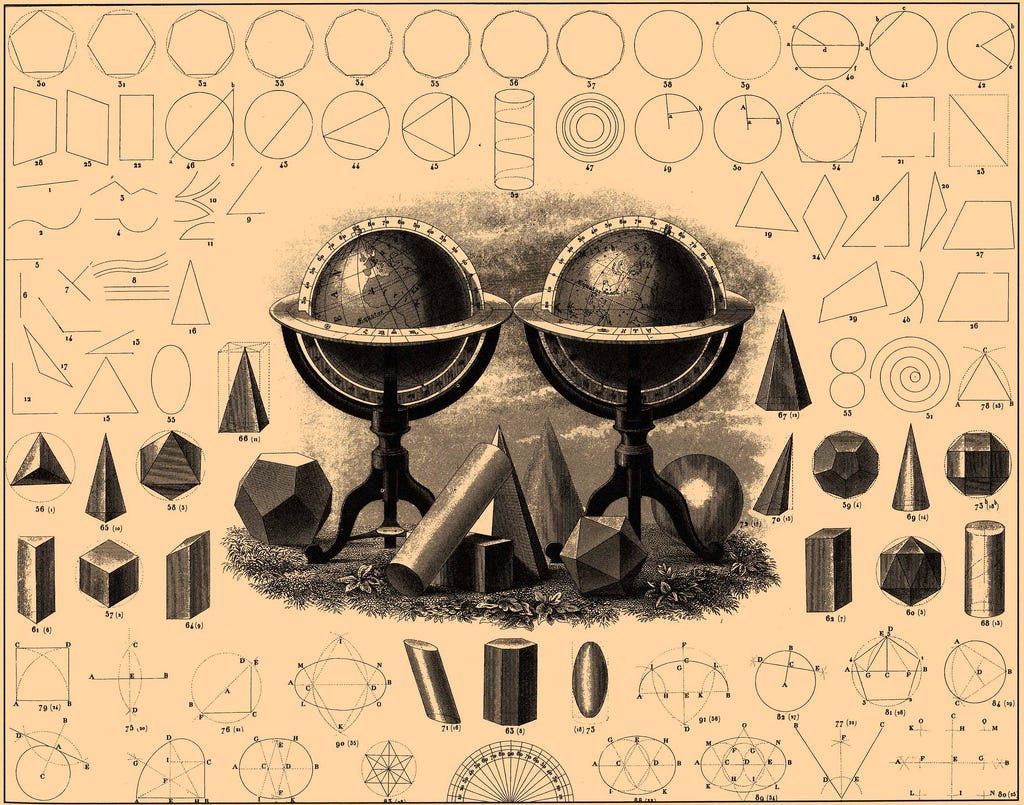

Characteristica universalis

The Latin term characteristica universalis, commonly interpreted as universal characteristic, or universal character in English, is a universal and formal language imagined by Gottfried Leibniz able to express mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical concepts. Leibniz thus hoped to create a language usable within the framework of a universal logical calculation or calculus ratiocinator. (Wikipedia, 2019)

Leibniz

was aware that political or philosophical debates and research did not

follow a mathematical method. According to Leibniz, mathematicians are

also likely to make mistakes like everyone else, but they also have some

tools to discover their mistakes. However, philosophers don’t have the

same tools as mathematicians, so they tend to make more mistakes. While there are Aristocians or Platonists in philosophy, there are no ‘Euclidean’ or ‘Archimedean’ in mathematics [God and Mathematics in Leibniz’s Thought, Mathematics, and the Divine: A Historical Study, pages 485–498].

According to Leibniz, it is necessary to mathematize the thought to end

the quarrels that are dominated by feelings rather than righteousness.

In order to formalize a significant part of thought, the symbols and

rules are required to emerge in mathematics. As Leibniz explains in his Preface to a Universal Characteristic,

characteristica universalis will reveal the alphabet of our thinking,

analyze the basic concepts. Based on those concepts, all things will be

judged in a definite manner [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, pages 5–10].

Thus, there will be no need for clashes between philosophers who

advocate two different views; they will sit next to each other and say

“calculemus!” (let’s calculate) and they will be able to calculate the

accuracy of their thoughts!

Leibniz’s

idea of characteristica universalis is a type of computational

formulation. This thought was based on matching basic or irreducible

thoughts with prime numbers. A number characterizes every basic thought:

the characteristic number. Let us cite an example given by Leibniz in

his article on Samples of the Numerical Characteristics [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, pages 10–18].

Suppose we are given the pairs of numbers (13, 5) and (8, 7), which

refer to the basic concepts of “animal” and “rational,” respectively, in

response to the proposition “Man is a rational animal.” The number that

characterizes the concept of “man” will be ([13 · 8], [-5 · 7]) = (104,

–35). Since there is an infinite number of prime numbers, a number or a

pair of numbers or a triplet of numbers can be assigned to all basic or

fundamental concepts. Other compound concepts can be obtained as the

product of prime numbers, and an entire language can be mapped.

Binary Number System

The

binary number system was known before Leibniz, but Leibniz was the

first to record it systematically and maturely. In a letter, Leibniz

wrote about how he dealt with the issue of the creation of everything

out of nothing and the binary number system. That is an example of the

masterful interplay of theology and mathematics (and even physics) in

Leibniz, as I shall mention later.

Leibniz designed a metal medallion (coin) on the creation and the binary system. The medal has the following expressions: Imago creationism (a picture of creation), Omnibus ex nihilo ducendis sufficit unum (In order to produce everything out of nothing one [thing] is sufficient) and Unum est necessarium

(There is need of only one thing). Leibniz, following the Pythagorean

doctrine, claimed that the origin or essence of everything was a number.

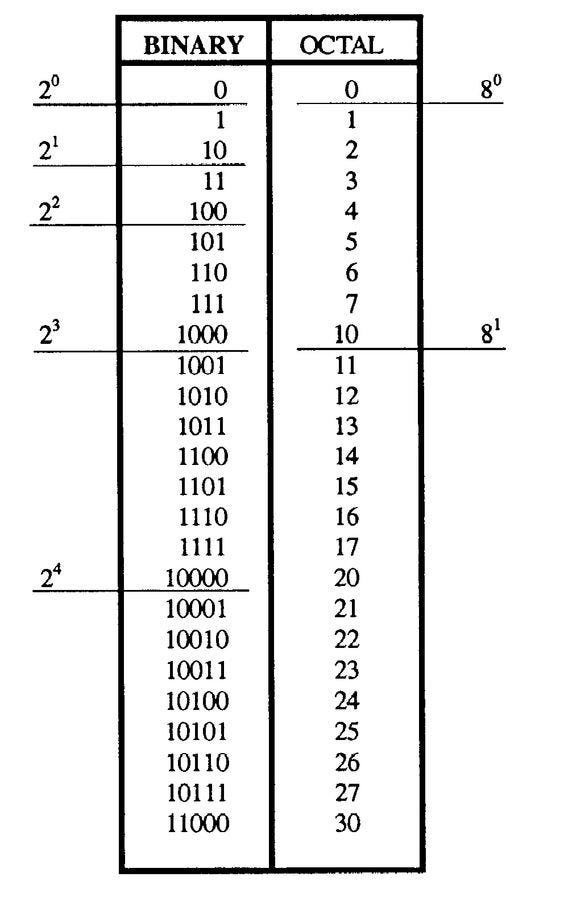

As is well known, in the binary number system, all numbers can be

expressed using 0 and 1. Interpreting 0 as “nothingness” and one as

“God,” Leibniz claimed that the binary system symbolized creation so

that everything could be expressed in this system. For Leibniz,

everything is a mixture of 0 and 1. According to this, all things have

come from the One, God.

For

Leibniz, the binary number system revealed the beauty and perfection in

God’s creation. That is, any single number in the binary system may not

appear to be beautiful, but when they are written one under the other,

the beauty appears due to the order within the overall system.

Similarly, there may be things in the world that we don’t like

singularly, but when we get the right perspective, we see that it is

perfect.

Leibniz’s

number mysticism does not end there; he said other things such as “God

loves odd numbers.” Since we do not want to extend this issue, we will

be satisfied with one last example. Leibniz says that the seventh day

after creation is a non-zero (“perfect”) number in the binary system,

adding on to the many numerical analogies that have been made on God’s

creation of the world in six days. It also states that 111 points

represent the Trinity [God and Mathematics in Leibniz’s Thought, Mathematics, and the Divine: A Historical Study].

Modern Proof Concept

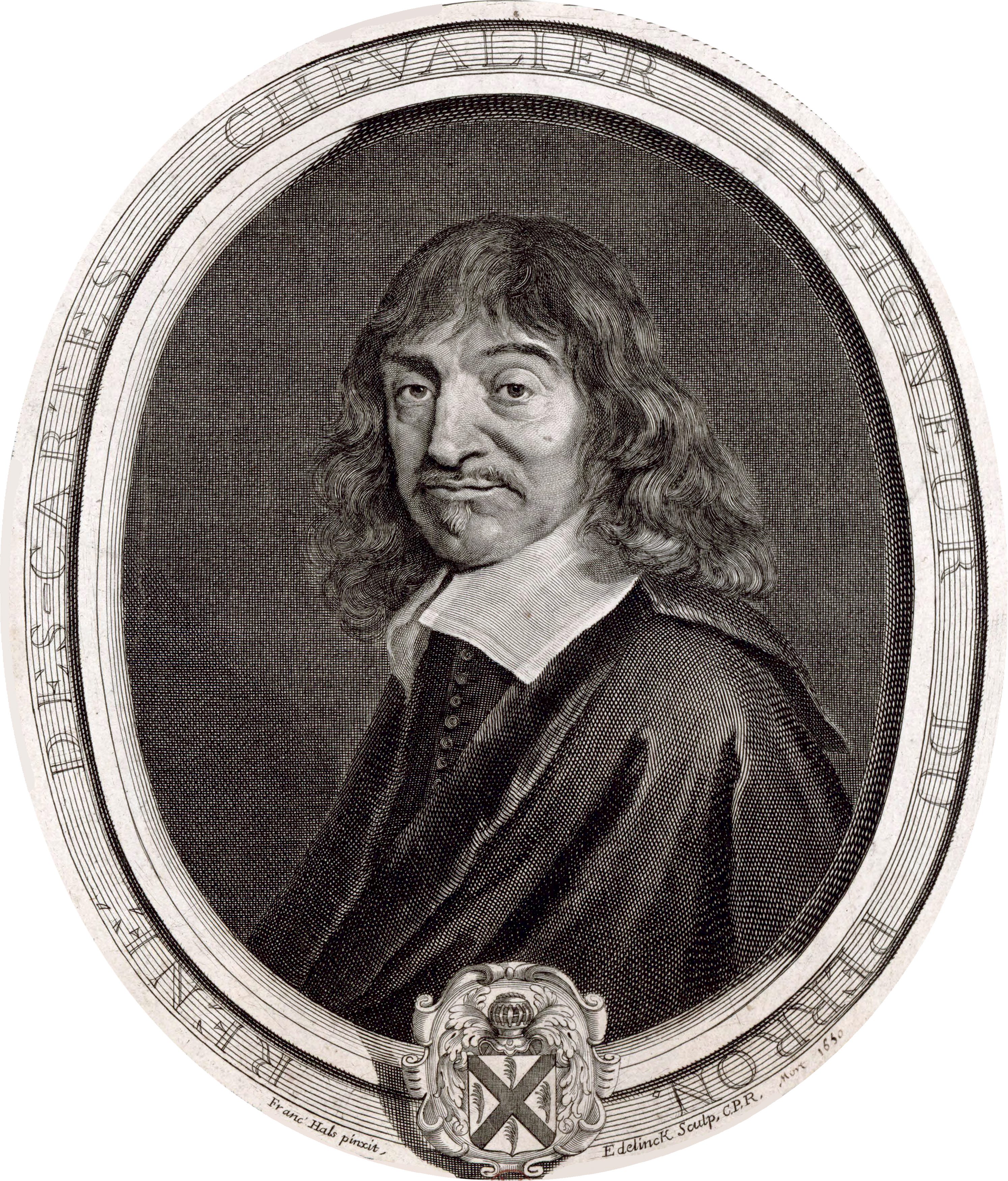

As

science philosopher Ian Hacking has shown, Descartes did not know what

proof was in a contemporary sense. Leibniz had a much closer thought to

modern proof (Hacking, 2002). He considered Descartes’ mathematical

accuracy independent of proof. For Descartes, even if an exact thing is

not proved, it is by itself true. Therefore, the truth value of

something and the proof given to it are not related to each other.

Let

us also recall that Descartes is not seeking proof, but rather

practical methods that give new mathematical results. What evokes the

concept of modern proof is that Leibniz realizes a proof is valid, not

due to its content, but because of its form. Accordingly, the proof is a

finite number of sequences of certain sentences according to specific

rules of logic, starting with particular identities. If we recall

Descartes’ method, he attaches great importance to intuition when he is

collecting new information, whereas in a Leibnizian perception of proof,

what is essential is to find “mechanical” proof of the sentence that we

have.

The

ideas of his time probably influenced the idea of proof presented by

Leibniz. As Hacking says (Hacking, 2002 pp. 202), it is customary to

find and remove a person who shook the thoughts deeply before him in

each period; Leibniz plays the role of such a person for his time.

There

is a plausible explanation provided by Leibniz about the emergence of

the idea of proof during his time. It is difficult to reach the

concept of modern proof when the geometry is taken as a measure of

precision: this is because geometric proofs are based mainly on their

“content.” The validity of such proofs is determined by their conformity

with the known properties of the geometric object being studied. With

Descartes’ algebraization of geometry, a way for the proofs to be

transformed into a formal form was opened.

Analytical

The

statements that are a predicate or identical to the subject or the

subject containing the predicate are called analytic. For example, when

we say “all people are alive,” for Leibniz, we mean that the concept of

being alive is within the idea of being human [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, page 11], so this statement is analytic. According to Leibniz, all mathematical truths are analytic.

It

is well known that Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) introduced the

analytic-synthetic distinction by diligently transforming Leibniz’s

concept of reality. According to Kant, analytic a priori knowledge is information obtained only by using logic. Synthetic a priori

is the information obtained by using time and space intuition.

According to Kant, arithmetic and geometric lines are synthetic a priori

based on intuition. Here we want to emphasize that Leibniz’s

implications for analytic and righteousness (although Kant has

transformed these meanings) have shaped the basic claims of logicians,

such as Frege and Russell. They attempted to reduce all mathematical

statements to logic in the early 20th century. Moreover, it is likely

that Leibniz’s idea that “axioms can be proved” influenced logicians.

Besides, Leibniz himself tried to present sound proof of the principles

used in a mathematical proof.

Leibniz’s

concept of proof and analytic concept complement each other because the

derivation of any statement from another statement while giving proof

corresponds to the concept of analytics.

Mathematica Divina

So

far, we have touched on some of Leibniz’s views on mathematics. One of

the issues raised in this paper is that Leibniz’s approach to

mathematics cannot be distinguished from his theological and

metaphysical or philosophical views. We have mentioned above that

Leibniz, for example, does not understand the binary number system as an

arithmetical issue. As Breger quoted, for Leibniz, mathematics and

theology were like the steps of a ladder ascending to God” [God and Mathematics in Leibniz’s Thought, Mathematics, and the Divine: A Historical Study, pages 493].

To understand Leibniz, the relationships he assumes between

mathematics, theology, and metaphysics are all matters that need to be

addressed. Such a complex issue cannot be dealt with in detail in this

short article; instead, I will merely address a few points to give the

reader an idea.

Leibniz

hoped that his mathematical achievements would draw attention to his

philosophical and theological ideas; after all, a mathematical

achievement is a sign of a strong mind. This “opportunism” of Leibniz on

a personal level is a reflection of another opportunism on the social

level of his era. As it is known, the Christian missionaries who went to

China used the mathematical achievements of Europe to impress the

Chinese and later Christianize them. Leibniz would approve it without

hesitation. In fact, for Leibniz, the characteristica universalis method

is the safest way to show the truth to those who do not believe in God,

because it will measure and show the accuracy value of everything like a

scales [God and Mathematics in Leibniz’s Thought, Mathematics and the Divine: A Historical Study, page 9].

In other words, the fact that the missionaries show the truth to

non-Christians with this computational method will be enough to lead

them to Christianity!

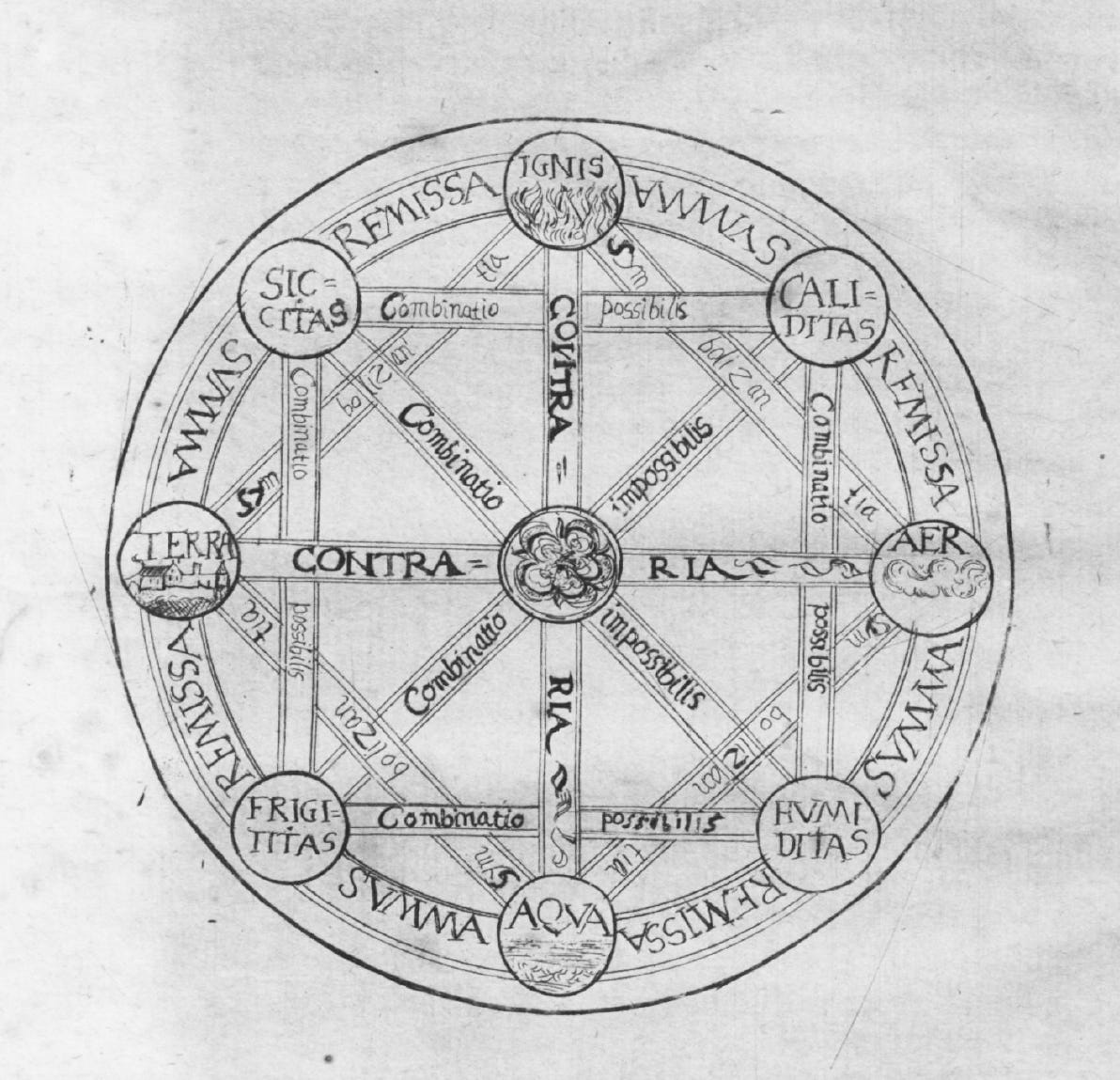

There is a metaphysical basis for Leibniz to use numbers for characteristica universalis. Leibniz dealt with the belief that “God created everything according to a measure, number, and weight,”

which was also expressed by Plato. Leibniz thinks: some objects have no

weight, so their weight cannot be calculated; some objects do not have

dimensions, so their length cannot be measured, but anything can be

counted. In summary, numbers are the essence of everything. According to Leibniz, God is a perfect mathematician. The act of creation took place with “divine mathematics” (Mathesis quaedam Divina). In his famous essay On the Ultimate Origin of Things, Leibniz says that the origin of all things is a “metaphysical mechanism” or “sacred mathematics” [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, page 151].

Everything in the world exists according to certain measures and laws,

and these laws are not only “geometric” but also “metaphysical” [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, page 152].

For

Leibniz, a world of free will, even if there exist cruelty and evil, is

better than a world without cruelty, evil and free will, as mentioned

in Theodicy and many other writings. That is the

explanation of God’s creation of a world with evil in it. In all

possible worlds, why did God create this world, not another world, in

this way?

For Leibniz, this is the perfect world! So, as an ideal mathematician, God has calculated all the possible worlds and created the best of them. An example of the best of all possible worlds is that lions are dangerous animals, but without them, this world would be less perfect. Besides, our assessment of the well-being of this world is limited to the events we have known and experienced so far. However, God has chosen this perfect world, taking into account all times and all creations [Leibniz, G. W. Philosophical Essays, page 149–155]. Another example given by Leibniz in this regard is that a person born in prison cannot judge that the whole world is evil by looking around. After all, for Leibniz, individuals see only a particular part, whereas God decides by taking everything into account.

Instead of Results

Leibniz’s

dazzling characteristica universalis program has never happened. David

Hilbert defended a formal mathematical form of Leibniz’s thought and

proposed a program accordingly. Kurt Gödel, who admired Leibniz, proved

the Deficiency Theorem and showed that programs such as characteristica

universalis are doomed to fail, not only in philosophy but even in

mathematics.

Leibniz’s

partly based metaphysics and theology on a mathematical level brought

about serious problems. Leibniz, in a sense, reduced everything to

calculation. For example, he reduced God to a calculator that solved

mathematical questions. It may seem paradoxical, but it is clear that

such a God does not have a say in matters that have no mathematical

solution. Leibniz says that in some places, even God cannot do eternal

operations. When he made God a mathematician, Leibniz understood that

even God was made incapable of where mathematicians were capable. Say,

for example, that God cannot perform infinite operations. Still, he can

see the result (just as the mathematician does not perform infinite

operations one by one while performing limit calculations, but can

calculate the outcome of those infinite operations).

Moreover,

Leibniz did not think that there could be more than one consistent

mathematical system in itself, taking absolute mathematical accuracy.

That raises a problem that Leibniz is not interested in, which

mathematics God uses. Mathematics occupies an important place in all of

Leibniz’s ideas from what we have written so far. According to him, a

mathematician must be a philosopher, just as a philosopher should be a

mathematician. In correspondence with L’Hôpital, Leibniz stated that his metaphysics was mathematical and could be written mathematically [God and Mathematics in Leibniz’s Thought, Mathematics, and the Divine: A Historical Study].

Moreover, according to Leibniz, mathematics is very close to logic; the

art of making new inventions, and metaphysics is no different from

that.

“I started as a philosopher, but as a theologian,”

says Leibniz. Today, if someone wants to understand Leibniz’s

philosophy, they still encounter the main issue; the relationship

between mathematics and philosophy, metaphysics, and theology in

Leibniz’s works.

Why we are so devoted to technology are a very significant question.

in order to know if it is or isn’t, you’ll have to define in the first place what it means to be a human being.

you cited becker in your last piece…but if you actually read becker thoroughly, you’ll find that he is essentially saying that civilization ITSELF is a kind of inhuman artifice made to AVOID the fundamental limitations of what a human being is…namely a mortal ape.

good luck with that defining it. nobody has managed to convincingly.

– it is sort of fun (when at word processor) tracking down the cause of errors, & hopelessly sort of piece together (backtrack) something fairly incomprehensible but the beginning foundation or intention of it is still apparent. That’s why I prefer SFnal as term for the genre / if it is simply reducible as genre /

The famous-ish authors you mention (in said genre) have very little grace in their writing, I think they recognise this (un/sub/consciously) & muddle/muscle through / they don’t do a good job of it (they don’t seem to read that much either / except perhaps in their “lean years” when paid to review &c.

— sorry for above, I don’t usually comment (online pointless shyness)

— or, no, I’ll retract my sorrow ( as = pointless)

Re: tech and dystopia, in May (during the first peak of my Plague Spring exasperation) I wrote:

“Our inter-related (interbred) families of ruling psychopaths, minus the Tech, would be of little concern beyond the strictly local, and they would, undoubtedly (minus the tech) be well under control by us vastly greater, in numbers, Serfs; in fact, without the tech, our Overlords wouldn’t be Overlords at all and neither would we be Serfs. Our Overlords wouldn’t even be wealthy, without the Tech: they’d be inmates in asylums for delusionally grandiose human-haters with cataclysmic sexual dysfunction. The Tech makes all the difference and for every light, or bridge, or cure the Tech has given us, sadly, there are a thousand massive links in the electrified chain of horrors we are each, in turn, chained to.

No powerful technology develops only as far as it should and then stops (self-limits) before the harm starts. Power not only corrupts, as the truism goes, but Power itself degenerates metastically; becomes grotesque in its baroque and tentacular extremes. Isn’t a nuclear bomber a metastically-degenerate form of the original apparently-benign invention of heavier-than-air flight? Isn’t a subcutaneous tracking chip… or a pharmaceutical implant, autonomously doping an ignorant human guinea pig with X-drugs on a timetable, or via a radio-networked trigger…. the metastically-degenerate forms of the miraculous apparently-benign invention of the syringe, and the personal computer, both? And isn’t the interval between original invention and metastically-degenerate iteration, in both of the above-cited technologies, terrifying brief? Try to imagine how grotesque these technologies will be just ten generations from now. How they will blacken and sizzle and ramify, snarling, then ramify further still.”