The Hidden Narrative in Middlemarch That 2021 Readers Will Spot

Diana Rose Newby on George Eliot's Approach to Contagion

When Taylor Swift first released the track list for her latest cottagecore album, a certain corner of literary Twitter lit up over the title of its eighth song. A little sadly for us, the lyrics of “Dorothea” don’t support the connection we quickly drew to Dorothea Brooke, fictional heroine of George Eliot’s Victorian novel Middlemarch. But regardless of whether Taylor had Eliot’s provincial character on her mind when she named the track, our reaction to it encapsulated the novel’s uncanny ubiquity in recent months. Since the start of the pandemic, it’s felt to me as though everyone has been reading Middlemarch.

On the face of it, this surge of interest in Eliot’s best-known work might seem unremarkable. But there’s a not-so-obvious reason that the 19th-century novel may have felt newly relevant for 2020 readers. Eliot probably conceived Middlemarch as a story about contagion—a plot with epidemic written into its core. And if we read it closely, the finished product is still “about” contagion. Middlemarch, in other words, is a pandemic novel without the pandemic.

You won’t have come across Middlemarch in the pandemic lit listicles that have proliferated this year. On its surface, this isn’t a contagion narrative—it’s a Victorian marriage plot. Eliot follows the lives of two protagonists, Dorothea Brooke and Tertius Lydgate, as each makes an unfortunate match: Dorothea to the mediocre and moody academic Edward Casaubon; Lydgate to town beauty Rosamond Vincy, who turns out to be scheming and spoiled. It’s through Lydgate, a young physician, that the novel veers most closely toward an explicit concern with contagious disease. When he moves to Middlemarch, Lydgate aspires to work at a fever hospital, with plans to open “a new ward in case of the cholera coming to us.”

Cholera never does come to Middlemarch in the way that Lydgate anticipates, yet Eliot’s notes for the novel indicate that she initially had different plans. In her Quarry for Middlemarch, the notebook where Eliot worked out the details and the order of the draft novel’s plot, she also recorded her extensive research into the highly contagious disease. In particular, she documents the progress of the Asiatic cholera pandemic of 1826-37, which reached Britain, where it would claim thousands of lives, in 1831. Published in 1871-72, Middlemarch spans the years between 1829 and 1832; as Mary Wilson Carpenter, for one, has pointed out, this historical setting exactly overlaps with cholera’s arrival on English soil.

While this conjuncture finds only oblique expression in the completed text—“cholera” appears all of nine times across the novel’s 86 chapters—the epidemic occupies a more prominent place in the pages of Eliot’s Quarry. She scrupulously charts the timeline of its appearance in Britain: “Quarantine to guard against it in England June 13, 1831. First cases occur at Sunderland Nov. 4. [A]ppears at Rotherham, Feb. 10, 1832 …” These notes also register the British government’s initial failure to prepare for the epidemic’s arrival, even as cholera made its way through Scotland and the northern regions of England. “Hitherto the legislature had been silent,” she writes, until “[a]ll at once, without apparently having lighted in any intermediate place, the disease appeared in London,” finally prompting a series of bills to be “hurried through Parliament”: political negligence that, for many contemporary readers, will strike a familiar chord.

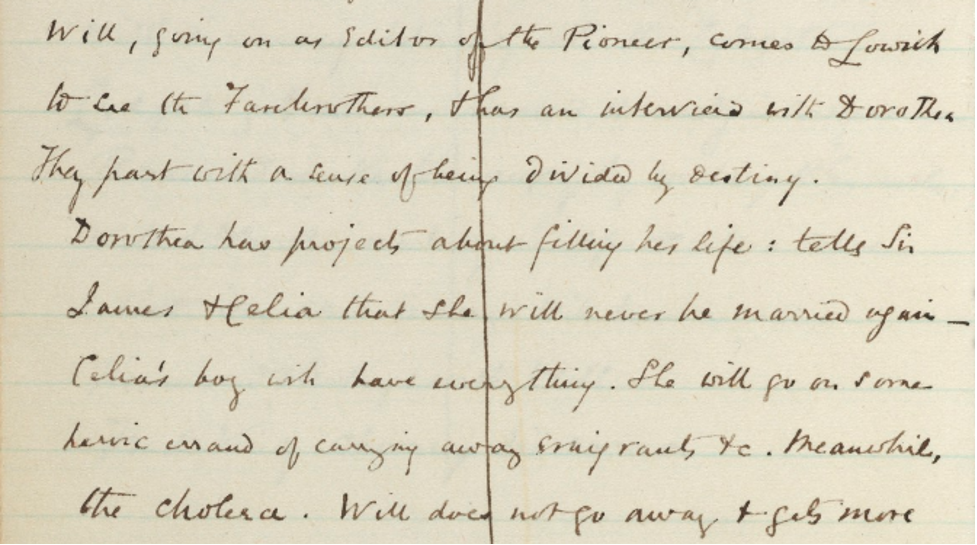

For Eliot, the figure of contagion takes on more metaphoric weight, structuring her pervasive focus on the risks and obligations of sociality.Even where the Quarry turns from this historical documentation to plans for Middlemarch, cholera maintains an evident foothold in the writer’s mind. Eliot folds the epidemic into her schema for the novel’s plot at one of its most pivotal intervals. On a folio with the header “Will Ladislaw and Dorothea,” she outlines the series of events that unite Dorothea with Casaubon’s cousin Will, whom Dorothea eventually marries after her husband’s untimely death, and despite Will’s unseemly intimacy with the wedded Rosamond:

Will, going on as Editor of the Pioneer, comes to Lowick to see the Farebrothers, has an interview with Dorothea. They part with a sense of being divided by destiny. Dorothea has projects about filling her life: tells Sir James & Celia that she will never be married again—Celia’s boy will have everything. She will go on some heroic errand of carrying away emigrants, etc. Meanwhile, the cholera. Will does not go away & gets more intimate with Mrs. Lydgate.

Meanwhile, the cholera. On the one hand, this tiny sentence tells us nothing new about cholera in Middlemarch; it relegates epidemic to a fleeting, background blip, the white noise of the novel’s larger world. On the other, it illuminates contagion as the interstitial force that shaped Eliot’s vision for the book, and which lingers in Middlemarch despite the fact that cholera was mostly excised by the final draft. The probability of epidemic remains “meanwhile”—ever-present, perhaps inevitable, yet easily overlooked. And I don’t just mean epidemic in a literal sense: for Eliot, the figure of contagion takes on more metaphoric weight, structuring her pervasive focus on the risks and obligations of sociality.

At its etymological roots, “contagion” distills the precarious possibilities that inhere in communal life. Combining the Latin prefix con- (together) with the basis tangere (to touch), the word indexes the necessary hazards of contact, the anxious threat of connectedness. These perils are central to Middlemarch, even and especially where actual contagious disease recedes into invisibility. Other forms of contagion gain purchase instead: infectious emotions, the transmission of gossip, the exposure of toxic truths. Spouses make each other sick, are drawn to other people helplessly, dangerously. Professional relationships cause cross-contamination when reputations are wounded by allies’ mistakes. In myriad ways, Middlemarch illustrates the ease with which we get tangled in the infectious web of our neighbors’ lives.

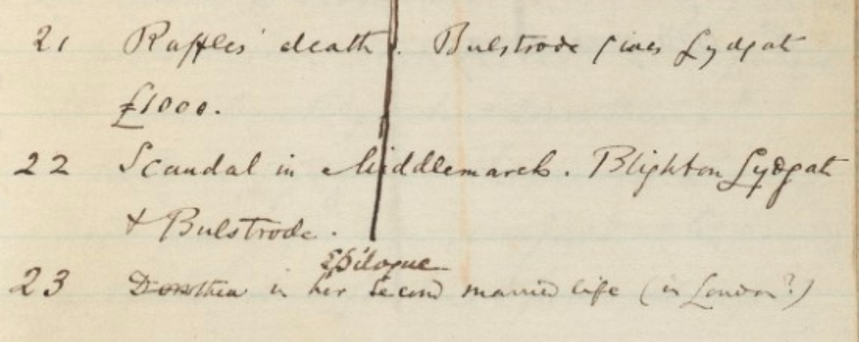

The metaphorical “logic of contagion” that Tina Young Choi has also observed in Middlemarch is arguably nowhere more powerful than in the downturn of Lydgate’s luck. A brilliant doctor with a promising career before him, Lydgate suffers not only from Rosamond’s selfishly manipulative influence, but also from his relationship with the sanctimonious evangelical banker Nicholas Bulstrode, who wants to fund the fever hospital. When multiple skeletons emerge from the closet of Bulstrode’s seedy past, the fallout hurts Lydgate almost as much as it destroys Bulstrode’s standing in Middlemarch. It’s not that Lydgate has committed any crime which can be proven on legal grounds; rather, he’s deemed guilty by association—“blighted,” as he puts it, “like a damaged ear of corn.” This is no throwaway metaphor: variations of the phrase “blight on Bulstrode & Lydgate” appear repeatedly throughout Eliot’s notes. As the Quarry attests, Eliot long planned to frame this turn of events in terms of infectious disease, the kind of contagion that might consume entire communities.

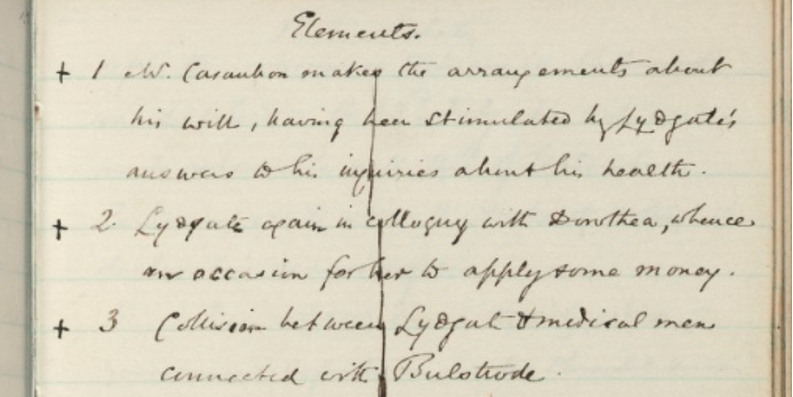

Moreover, and beyond the story of any single character, contagion’s organizing logic informs the whole of Middlemarch’s plot. Over the novel’s course, Eliot traces the links that bind all of her characters in a network of physical and emotional exchange. Here again the Quarry is telling: as represented in her notes, Eliot’s careful sequencing of points of contact between characters bears more than a passing resemblance to the way she plots and replots the cholera epidemic’s chronology. First recounting cholera’s geographic movements throughout England, she later revisits the epidemic in order to situate it within a more scaled-back sociopolitical history; on a list simply titled “Dates,” cholera appears right in the middle, between the 1830 “Opening of Liverpool & Manch[ester] Railway, April” and 1833’s “Reformed Parliament, Election Jan[uary].” Likewise, she fills the Quarry’s pages with various formulations of the social “conditions” and “elements” that are context for character relationships, and that alternately make these relationships blossom or rot.

In both cases, what seems to interest Eliot are the subtle forces of causality that interlink seemingly unrelated people and events. The finished novel gives sprawling shape to the scope of these links; among the most-discussed features of Middlemarch is the vision it evokes of social entanglement in all its depth and reach. In so doing, the novel also expresses a view of interconnection as potentially poisonous—an impression that mere proximity to other people will propagate shared harm. At the level of sheer form, Middlemarch’s multiplot structure is a contact-tracing map.

For those familiar with 19th-century fiction, Eliot’s treatment of epidemic might not seem to distinguish her from other novelists of her time. Whole books have been written about the prominence of contagion in the Victorian literary imaginary; a marker for the physical body’s very real vulnerabilities, contagion also harbored symbolic potential for writers of the period. It was a favored device in the novels of Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell, who used communicable illness to sentimental ends, often to critique the social inequities that made certain groups of people more susceptible than others to disease. Conversely, metaphors of contagion were also made the vehicle for racist and xenophobic rhetorics. Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for example, links its eponymous vampire with the idea of transmissible disease, and is commonly read as representing Victorian anxieties about colonial relations and miscegenation.

Eliot makes the case for a mode of social consciousness in which all actions are measured by their effects on the community.In Middlemarch, however, Eliot’s political and moral investments don’t take their fullest emotional force from pity or fear toward the potentially infectious other. Instead, it’s the potentially infectious self to which she draws her readers’ gaze. Again and again, Middlemarch stresses how readily we ourselves can hurt our neighbors by becoming conduits for contagion, both literally and otherwise. By virtue of the closely networked nature of social life, Eliot’s characters regularly transmit harm to the other people crowded in their sphere, often without knowing or intending it. “You don’t mean your horse to tread on a dog when you’re backing out of the way,” as the benevolent surveyor Caleb Garth explains; “but it goes through you, when it’s done.”

For Eliot, this way of thinking works in service of an ethics that we might understand as contingent accountability. In her didactic way, she makes the case for a mode of social consciousness in which all actions are measured by their effects on the community, and in which the responsibility for these effects is understood as collective. Through the logic of contagion, Middlemarch coaxes readers toward a sense of self as embedded in a meshwork of relations with people whom our choices intimately affect, however removed from us those people may seem. As Eliot’s storytelling maintains, we have an obligation to these connections; they require us to cultivate practices of ongoing harm reduction and care.

If many of us found ourselves turning to Middlemarch with new or renewed attention last year, perhaps it’s because the novel offers a framework for grappling with the existential dilemmas forced on us by COVID-19. Eliot shows us one way of reconceiving the self in a time of pandemic: a radical decentering that shifts our perspective from individual life to the interdependent health of the web. In both content and form, Middlemarch enacts the collectivist mindset required to reckon with contagion across multiple scales—from the local, neighborly level of wearing a mask and staying home, to the greater abstraction of locating the self in a contact-tracing sprawl. All in all, the novel serves as a relevant guide for navigating the unfamiliar vantage points that our present crisis opens up.

At the same time, however, crisis isn’t the point of Middlemarch. Because Eliot buries contagion beneath the finished novel’s surface, she tenders its collective ethics not as an urgent response to emergency, but as a necessary precept of social membership in a more general, everyday sense. Eliot treats contagion, or things like contagion, as a latent condition of communal being: a sometimes hidden yet continuous context underpinning public life. This approach becomes all the more essential for contemporary readers on the other side of 2020, with the pandemic continuing to drag on and crisis burnout setting in. What Middlemarch gives us is a sustainable model for attuning ourselves to contagion’s probability—a more careful, patient way of living with and for others, even after disaster subsides.

Screenshots taken from the Harvard Library’s Digital Collections, which are open for sharing and adapting under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Diana Rose Newby

Diana Rose Newby is a PhD candidate in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. Her writing has been featured or is forthcoming in Politics/Letters, Texas Studies in Literature and Language, an edited volume on the health humanities, and a pedagogy handbook for early-career college instructors. A native of California, she currently lives in Harlem with her partner and their cat. https://lithub.com/the-hidden-narrative-in-middlemarch-that-2021-readers-will-spot/