Ying Li’s Ecstatic Landscapes

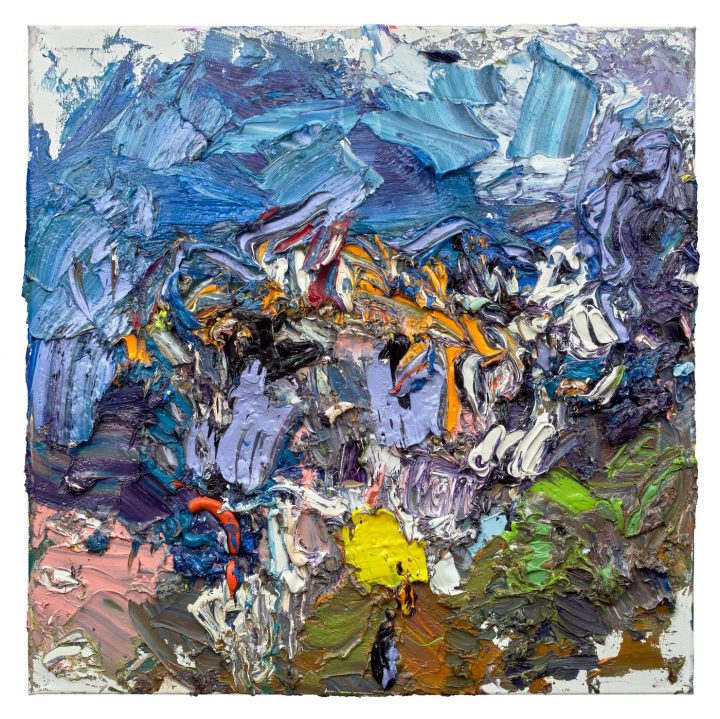

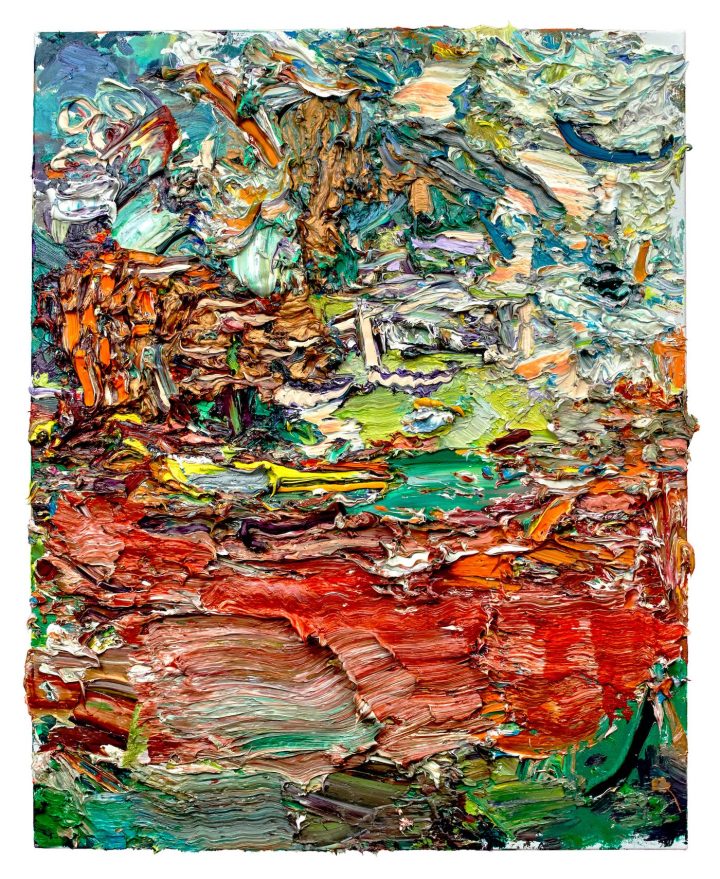

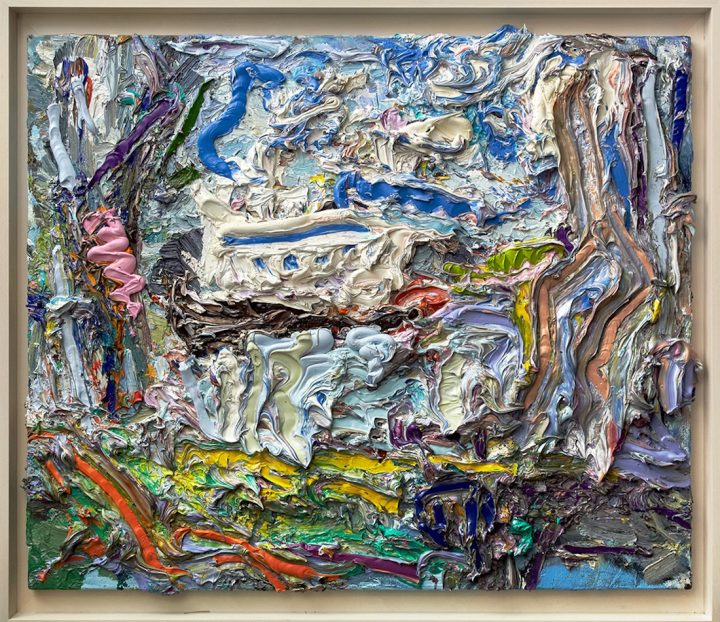

Li paints on site, which she indicates in her titles, such as “Telluride, Valley of the Hanging Water #3” (2019, oil on linen, 24 x 24 inches) and “Rosendale Trestle” (2019, oil on linen, 24 x 30 inches). When she makes large paintings in her studio, she evokes the city as subject matter, as in “Writing the City #3” (2020, oil on linen, 74 x 58 inches). These three paintings, along with 11 others, will be featured in her upcoming exhibition, Ying Li: Alterity, at Pamela Salisbury Gallery, Hudson, New York (June 27–July 26, 2020).

The other thing that struck me about Li’s work — an impression that has stayed with me — is the way she enlivens what many have considered an exhausted possibility: the vigorous application of thick paint in service of a perception of nature. You might think, from this description, that I’m writing about a painter working in the late 1950s, in the wake of the Abstract Expressionists, who showed in an artist-run gallery on Tenth Street in New York City.

This knot is what I began thinking about while contemplating Li’s work. And the longer I looked at it, the more I was convinced that even the most positive reviews written about her paintings failed to address a key aspect of her artistic development. It seemed to me that Li is free of the baggage associated with thick gestural painting. How had she arrived at a place that was not at all nostalgic for the past, or mannered in its gestures?

I decided to contact Li about her early history, previous to her arrival in America, which I felt would be a key to what I was seeing, and not seeing, in her work. In 1983, when she immigrated to New York from China, Li was already an accomplished artist working in two styles that the art world would never have recognized, then or now: traditional Chinese ink-wash landscapes and Soviet-style propaganda paintings.

In an email Li sent me (June 23, 2020) in response to my questions, she wrote that she had “painted mural paintings of Mao’s portraits in the village where I was sent during Cultural Revolution.” She also “painted historical propaganda paintings commissioned by the government when I was teaching at Anhui Normal University.”

In this same email, she stated:

I studied traditional Chinese ink wash painting in college, from 74-77. It was a requirement for students, I was one of them, whose concentration was Western oil painting. I hated it at the time and thought it was like painting with soy sauce. All I wanted was to paint with color. I was foolish.Li was not permitted to apply to colleges outside of Anhui, a landlocked province. Anhui Normal University, where she studied art, was “the only university that offered Fine Arts study in Anhui Provence at the time.”

By the time Li traveled to the United States, she was in her early 30s. It was the first time that she saw oil paintings by artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Chaim Soutine, Willem de Kooning, and Lois Dodd. Not one to look back, she also took classes at Parsons School of Design, where she studied with Leland Bell, John Heliker, and Paul Resika, three strong-minded, unfashionable, modernist painters who engaged in rigorous arguments with the institutionally supported direction that art has taken since the mid-1950s.

This is what I find remarkable about Li’s work. In order to make it, she had to reinvent herself in her 30s and already deeply grounded in two other traditions. Against all odds, she decided she was going to have a second act. Moreover, her encounters with strong-minded teachers resulted in work that in no way resembles theirs. Her interest in exploring many aspects of a single a motif is something she shared with both Bell and Resika, but that is about as far as the connection goes.

Li’s dramatic and remarkable reinvention, her joyous exploration of color, which she had only been able to dream about in China for so many years, brings to mind another Asian artist, Kenzo Okada (1902-1982), who was a highly respected realist painter in Japan when he came to New York in 1950, where he began making sensitive abstract paintings that still have not gotten the attention they deserve. I have often wondered if one reason for this is that Okada’s paintings seem too Asian for New York tastes.

Absorbing lessons from Vincent van Gogh, Li uses the direction of the brushstrokes to convey motion, the continuously changing landscape, and the world in constant transformation. Once we know Li’s history, it is hard not to think that the joy we see in the work is rooted in her youthful dreams of painting in intense color while luxuriating in oil paint’s materiality.

The subject emerges out of the structuring of the marks, all of which are different. While vigorously applied, it is evident how much control Li possesses over her medium. The thickness of the paint allows for both fast and slow strokes, and for the muscle memory of years of calligraphy to kick in.

This is what I thought about when I was looking through images of the work in her upcoming show, that her previous reviewers, by emphasizing a connection to Abstract Expressionism, however well intentioned, overlook the deeper roots of Li’s mark-making, which is calligraphy.

Direct and deft, the individuality of these marks seems possible only after years of practicing calligraphy. This is part of what Li was able to transform from her background into her reinvented method. She did not completely reject her past, but rather turned it into something that was new for her. In the process, she came up with new ways to celebrate color.

Chinese ink wash landscape painting is made of abstract calligraphic marks. It is not about resemblance but essence. By bringing that knowledge and experience to the colors of oil paint, Li has created something all her own. That she did so at an age when many artists would already be set in their ways, is miraculous, and the joy of that turning point in her life and career radiates throughout all her work.

Ying Li: Alterity opens at Pamela Salisbury Gallery (362 1/2 Warren Street, Hudson, New York) on June 27 and continues through July 26.

hyperallergic.com