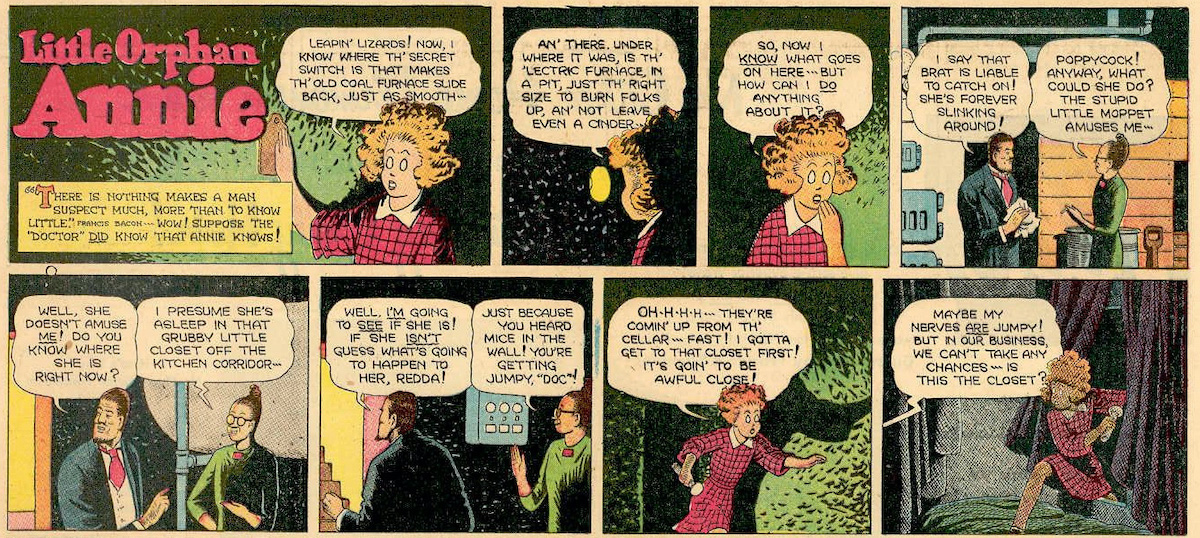

When we first meet her, Annie is, appropriately enough, in a

tight and uncomfortable spot, as she’ll be time and again for the

duration of her event-filled existence. An orphan, without even the

luxury of a family name (“just Annie” as she’s quick to say), constantly

under the stern glare of the orphanage’s bullying headmistress (the

prune-faced Miss Asthma), forced to eat mush and scrub the floors, Annie

remains not just resilient but even buoyant and chipper as she prays

for some nice adopted parents.

She lives a day-to-day existence but is always hopeful for what

tomorrow might bring. If today you’re eating gruel and being pushed

around, the next day might deliver something better, as it does for

Annie when she’s taken under the wings of the good-hearted Miss Fair

and, eventually, “Daddy” Warbucks, her long-term guardian and perennial

savior. The trick for Annie is to keep watchful and alert, with an eye

out for opportunities, a willingness to speak out when necessary, and a

heart stout enough to fight for what’s right.

From the very first strip, which debuted today, ninety six years ago in the

New York Daily News,

Harold Gray established the emotional tenor that would distinguish

Little Orphan Annie. Compared to the elaborate and carefully-conceived

novel-length narratives Gray created in the 1930s and 1940s, the early

Annie strips might seem a bit crude: the drawings are roughhewn

(although his line fluid), the plotting has a shambling,

seat-of-your-pants haphazardness, and there are occasional longueurs as

Annie dawdles around while Gray waits for the next bit of inspiration to

hit.

But the main components of the strip are there from the start: at the

heart of the series is Annie, much-abused but spunky enough to fight

back with a sharp tongue and a good left hook. She serves as a moral

litmus test, and around her gathers a polarized cast of characters: on

one side are the mean-spirited, snooty types who make life rough for her

(prototypically Miss Asthma, but also Mrs. Warbucks and various spoiled

children of wealth); against them stand the good souls whose instincts

are to help Annie (Miss Fair, “Daddy” Warbucks, and the poor but kindly

farmers, the Silos). Before six months are out, Annie has acquired

another best friend, as fierce and essential a protector in his own way

as the wealthy “Daddy,” Sandy the dog.

The emotional bonds that unite these characters are established

almost instantaneously. Annie and “Daddy” immediately recognize each

other as kindred spirits. Just as Annie suffers at “the Home” (her name

for the Orphanage), “Daddy” also has an unhappy home, his wife a social

climbing shrew who cares more about pleasing Society than taking care of

either him or their adopted daughter. Annie is a little girl in need of

love and protection; “Daddy” a gruff but decent man, successful in

business but unlucky in his marriage, hungers for the warmth of family.

An intuitive alliance is forged between Annie and “Daddy” at their first

meeting. Similarly, the love between Annie and Sandy derives from

shared characters traits: as is often noted in the strip, both are

orphaned mongrels who have had to fend for themselves from an early age

and both possess an instinctive gallantry that keeps them loyal to

friends and willing to do battle with enemies. When one is wounded, the

other jealously acts as a sentinel and nurse.

*

Harold Gray was thirty years old when he created Annie and, despite

the occasional storytelling misstep and moments of uncertainty, he knew

what he was about. This confidence came from the fact that Little Orphan

Annie didn’t just spring up full-blown in a fit of wild inspiration.

Rather, the strip was the culmination of many years of hard work and

ambitious planning. Everything in Gray’s early life—his family

background and upbringing, his schooling and military service, his

wide-reading and early career—went into the making of Little Orphan

Annie. Like his famous creations, Gray was a fighter and a

straight-shooter. To look at his life is to see the foundation and

building blocks of his work.

He was born in Kankakee, Illinois, a small burg nestled in farmland

just outside of Chicago, on January 20, 1894. The original “Gray

homestead,” near the small town of Chebanse, Illinois, was first cleared

by the cartoonist’s grandfather, William Wallace Gray, in 1870. Gray’s

father, Ira Lincoln Gray, was the youngest of six children and perhaps

was delegated the traditional role given to the family baby of looking

after the mother and father in their old age. Certainly Ira Gray didn’t

move far from his parents even after marrying Estella M. Rosencras in

1893 and fathering Harold the following year. Kankakee was not that far

from Chebanse and young Harold had many memories of his grandparents.

William Wallace Gray was an active Methodist and his grandson Harold

would remain a church-going Protestant all his life (although in later

life the cartoonist would occasionally fall asleep during sermons).

Religion was important to Harold Gray and its exact nature has to be

understood. He was very much a liberal Protestant and universalist: true

religion for him was not a matter of reading sacred texts literally or

conforming to the fine points of doctrine, it was about being

open-hearted, charitable, and neighborly. In Little Orphan Annie, Gray

repeatedly emphasizes that all religions have access to God. Annie’s

long list of friends would include Jews, Muslims, Confucians, and even a

Sikh (the tall, turbaned sword-wielding Punjab). In 1927, Annie is

impressed with a minister who argues that “one religion is ‘bout as good

as another just ‘so long as yuh live up to th’ one yuh b’lieve in. He

says this thing of a lot o’ different kinds o’ churches crappin’ over

which is best is th’ bunk.”

What sort of boy was Harold Gray? There’s plenty

of evidence that, like Annie, he was a scrapper, never one to run away

from fisticuffs.

The geography of rural Illinois left a strong mark on Gray’s

imagination, as can be seen if he’s compared to his Wisconsin-born

colleague Frank King, who created Gasoline Alley. In King’s work, the

country-side is always rolling and sloping, with cars constantly

sputtering up hills or flowing down valleys. In the early Little Orphan

Annie strips, by contrast, once our heroine leaves the city, the

countryside is as flat as a quilt spread out on a bed, each acre of

farmland its own perfect square, with stacks of hay and isolated silos

the only protrusion on the land. The flatness of the prairies, the

prostate manner in which the horizon spreads out as far as the eye can

see, spoke to something deep in Gray’s imagination: it perhaps explains

his sense of the isolation of human existence, the persistent feeling of

loneliness his characters voice, and their commensurate need to reach

out to Annie and create strong (although temporary) families with the

orphan as their child.

In 1901, the elder Gray sold the family homestead near Chebanse to

his youngest son, who continued to raise horses and cattle there,

perhaps out of filial obligation. Young Harold must have been busy on

the farm because often he wouldn’t go into Chesbanse for three or four

months at a time; but once the busy season was over, the family would

resume their many personal connections with the town. “We read the

Chebanse Herald, banked with the Porch Bank, patronized H. Sykes for

drugs and our close and dear friend and doctor was Dr. S.R. Walker,”

Harold Gray recalled of those years. “I still remember Frank Spies, Jay

Lane, Ed Grace and big Ed Butte, the auctioneer who did not live there

but who sold many of the big farm sales in that area. We shipped cattle

now and then from the little siding in Chebanse, to Chicago. We bought

our implements and groceries in Chebanse.”

Gray’s grandmother died in 1905, his grandfather less than a year

later. Immediately after the death of his father, Ira sold the homestead

and moved to a new farm in Tippecanoe, Indiana, near Lafayette. The

move, along with a later career change, indicates that farming didn’t

come easy to Ira and his family.

This was hardly a personal fault: throughout the late 19th and early

20th century American agriculture was in a state of near permanent

crisis. Technological advances had greatly increased the productivity of

farms but this was offset by a corresponding drop in commodity prices.

Tight credit, based on Wall Street’s favored policy of keeping the

currency on the Gold Standard, meant that many farmers were perpetually

mortgaged (which was certainly the case with the Gray’s). Nor

surprisingly, the mean-hearted banker eager to foreclose on farms and

kick out widows and orphans became a staple of popular literature (and

would show up more than once in the early days of Annie).

There was a positive side to the farmer’s lot, often highlighted in

populist political rhetoric of the era. Farmers saw themselves as the

backbone of America, the hard toiling sons and daughters of the land

whose simple old-fashioned virtues kept the nation fed. By contrast,

city life was seen as corrupt, soft, and decadent. Occasionally this

sort of populist anti-urbanism is voiced in Annie, although it’s never a

strong motif because the strip’s eponymous star is, after all, very

much a city girl.

Harold Gray was genuinely divided about farm life, as can be seen in

his portrayal of the Silos, the first of many hardworking but

impoverished farmers who shelter Annie. Byron and Mary Silo have all the

salt-of-the-earth virtues that you could want: they are diligent,

persevering, and generous. But they also lead lives of grinding drudgery

and economic precariousness. Gray’s gift for reportorial realism, one

of his distinctive traits as a cartoonist, shines in his delineation of

farm chores, whether it’s the milking of cows or the churning of butter.

Gray was especially sensitive to the plight of the farmer’s wife,

forced by straightened circumstances to be dowdy and to forego the

luxuries enjoyed by her city sisters. In considering the distress of the

countryside, Gray was even willing to entertain the idea, suggested by

“Daddy” Warbucks of all people, that farmers should unionize.

*

Gray must have been fairly young when he decided that a farmer’s life

was not for him. Even before starting college, he started laying the

groundwork for a journalistic career, working as a gofer and

jack-of-all-trades at the Lafayette Morning Journal, where his earliest

cartoons, as well as some news stories, saw print. For $10 a week, the

teenaged Gray did all sorts of odd jobs for the paper, with an extra $1

for any editorial cartoon he drew. “I serviced advertising, collected

bills, solicited ads and rode the Journal’s motorcycle whenever I

could,” he recalled half a century later.

What sort of boy was Gray? There’s plenty of evidence that, like

Annie, he was a scrapper, never one to run away from fisticuffs. Gray

recalled that when young his neighbors included “the Giertz children,

especially Freddy with whom I used to fight what I fondly hope were

draws on every opportunity – I surely never could beat him.” At college,

Gray’s major form of recreation was boxing. In a nostalgic 1955

sequence of Annie, a boyhood friend of “Daddy” Warbucks recalls the

great boxers of the early 20th century: “Ah , yis, Annie,” he

reminisces. “Those were th’ days. Real fighters! Jimmy Clabby. Mike

Gibbons. Ted Lewis. Kid Graves.” These pugilists were all active when

Gray himself was young, and it’s likely that he saw their matches.

Combativeness is often a mask for shyness and insecurity. Perhaps

Gray’s fighting spirit hid another side of his character. There is a

recurring character type that Annie meets several times in her

adventures: a young boy, either an only child or the youngest of a large

family, who is socially awkward but gifted. Sometimes the boy is a

quiet loner given to ruminating alone with nature, or he is a bookish

farm boy who is slightly disdained by the better-off town kids because

of his lack of the social graces. Often he is a boy who is good with his

hands and likes to draw and make his own toys. Equally often he is also

a boy who dreams of succeeding in the bigger world once he moves away

from his parents. Sometimes the boy is thwarted by his family’s lack of

ambition or fearfulness in the face of risk. The first of these boys is

Itchy Jones, introduced in early 1930, but variations of the type recur

in the strip until shortly before Gray’s death in 1968. When reading

about these boys, it’s hard not to see them as partial portraits of the

artist when young. The repeated lesson this type of boy learns is not to

be satisfied with his lot in life but to dream big and work hard.

Even if Gray didn’t inherit much money or land from his parents, his

family left him a lasting political legacy. It’s all there in the

middle-names: Ira Lincoln Gray, born two years after the assassination

of the Great Emancipator, fathered Harold Lincoln Gray. Gray’s ties to

Lincoln were many: Illinois is, of course, the Land of Lincoln and the

Chicago Tribune,

home of Gray’s work for 50 years, first made its reputation as a

national paper right before the Civil War when it became the chief

editorial supporter of the lanky, frontier lawyer who became the first

Republican president.

Often in the 1920s, Gray would set aside a Sunday in February to have

Annie mark Lincoln’s birthday. “He had everything it takes to make a

reg’lar honest-to-goodness he-man,” Annie noted about Lincoln in 1928.

“He didn’t have money or a lotta swell relatives backin’ him … What

color folks were, or where they came from, didn’t cut any ice with him.

Folks were all folks to him an’ had feelin’s. So he stuck up for th’

colored people. He wanted them to get th’ chance they’d never had ‘fore

then.” These paeans to Lincoln disappeared as Annie became more popular

nation-wide, perhaps in deference to white southern readers.

This Lincolnian inheritance is the key not just Gray’s lifelong

commitment to Republican Party but also the broader outlines of his

worldview. To simply describe Gray as a hidebound conservative doesn’t

do justice to his thinking. For one thing the nature of conservatism and

the Republican Party changed radically from Gray’s day (the Republicans

after all were the Northern party and, for much of Gray’s lifetime, the

party supported by most African-Americans). Gray’s conservatism wasn’t

the penny pinching creed of Calvin Coolidge, fearful of spending money

on the poor; rather it was the expansive ideology of Lincoln, a faith in

free labor, hard work, and opportunity.

Rare among cartoonists of his era, Gray was constantly critical of

racism and anti-immigrant nativism. In 1927, Annie and Sandy are on the

road and hungry. A black railway cook gives them food, leading the waif

to draw the appropriate lesson: “That just goes to show yuh, Sandy, just

‘cause a bird isn’t our color is no sign he isn’t right, see?” Or as

one of Annie’s father-figures notes, “Breed or creed or doesn’t count

with regular folks.”

With his Lincoln-inspired faith in hard-work and upward mobility,

Gray went off to the university in 1913. He had hoped to study

journalism at the University of Wisconsin or the University of Missouri

but funds were tight so he had to stay closer to home and study

engineering at Purdue. He paid for his education by working all through

university. In 1963, reporter Barbara M. Hawkins vividly described

Gray’s youthful work ethic. “His determination and tenacity were honed

as a boy,” the journalist noted. “At 20 he was on the crew that dug the

Van Orman-Fowler Hotel—10 hours a day for 20 cents an hour. For a time

he had to shun newspapering, because the weekly $12 he made for pick and

shovel work was $2 more than the Journal was paying.”

Work colored Gray’s university days. “No money, no time for social

life except to box,” he once recalled. “I could box an hour and then go

to class or study.” In a 1960 sequence, “Daddy” Warbucks returns to his

old Alma Mater (which bears a striking resemblance to the Purdue

campus), and reflected rueful on his own truncated academic career. “But

I never had any girl in those days!” Warbucks tells Annie. “Couldn’t

afford a girl! No time of (for?) ‘em anyway, me working nights and

Sundays!” Because of his poverty, Warbucks shyly avoided asking out a

girl he had a crush on: “I was a grimy workingman earning my way in the

mill! I was broke and I was ugly!”

Between work and studies, Gray found time to draw cartoons for

Purdue’s yearbook, The Debris, which he also edited in his final year.

His undergraduate cartooning showed little signs of his eventual talent:

his yearbook drawings tend to be raw and overly cluttered with wiggly

lines. His early characters have the malleable anatomy of rag-doll

monkeys, with arms as long as their bodies.

Shortly before graduating, around 1917, Gray decided that he wanted to work for the art department of the

Chicago Tribune, then solidifying its position as the Midwest’s leading paper. Gray’s goal was assisted by the fact that that the

Tribune’s

revered editorial cartoonist John T. McCutcheon was both a Purdue

alumni and a possessed a keen eye for up-and-coming talent. At various

points in his long life, McCutcheon gave crucial aid to Clare Briggs,

Frank King, and Milton Caniff, among others. With McCutcheon opening

doors, Gray scouted for jobs at the paper. The art department was full

up but the news room was willing to hire Gray as a cub reporter for $15 a

week. The experience was short-lived because the art department quickly

found an opening, but it proved valuable (as did his earlier reporting

for the Lafayette Morning Journal). Little Orphan Annie would become the

most journalistically-oriented of all comic strips (at the time or in

the 1920s), always reworking headline scandals about political

corruption and rampant gangsterism into compelling melodramas. Gray

retained a respect for the ink-stained boys of the press all his days;

unlike other conservatives he bore no ill-will to the media and always

showed reporters and editors in a good light.

Gray’s burgeoning career at the

Tribune hit a detour with

America’s entry into the First World War. Drafted into the army, he rose

to the rank of Lieutenant and spent the war working as a bayonet

instructor in Georgia. A striking photograph from the period shows the

young Gray as thin-lipped, severe, intently-focused and heavy browed (as

an older man he would lose his hair and his face would balloon out to

achieve a Warbucks-like roundness).Again, the experience was brief but

formative: to the end of his days Gray would remain a card-carrying

member of the American Legion. Even in the war-wary years before the

attack on Pearl Harbor, military veterans would figure prominently in

Annie as bearers of a hard-won wisdom of the necessity of military

preparedness. By the 1950s and 1960s, almost every Annie story featured a

decent, manly veteran.

After the armistie, Gray rejoined the staff of the

Chicago Tribune.

It was an opportune moment because the paper was being remade by two

fellow vets who ran the paper on behalf of their wealthy family, Robert

Rutherford McCormack and his cousin Joseph Medill Patterson. Outsized

personalities, the two men took monikers from their military ranks,

styling themselves Colonel McCormack and Captain Patterson. Working

together the Colonel and the Captain aimed to transform the

Tribune

from being an important regional journal into the hub of a national

media empire. Comics were a key part of this plan, as they wanted to

create a stable of strips that could be syndicated nationally and spun

off into movie adaptations and, eventually, radio programs.

Captain Patterson was the key man pushing a forward strategy on the

comics front, a task to which he brought his colorful past. Born in 1879

to one of the wealthiest of American families, Patterson rebelled as a

young man, working as foreign correspondent (he covered the Boxer

Rebellion in China), and, like more than a few scions of the ultra-rich

of the day, taking up the cause of socialism, and writing plays and

novels denouncing the iniquities of the American rich. These activities

offended Patterson’s family, who were, after all, the owners of the

nation’s leading Republican newspaper, but they served Patterson well

when he became an editor.

Patterson had a feel for the rawness of progressive-era America, its

class inequalities and seething turbulence. He also had strong narrative

sense born of his aborted literary career. For him, a newspaper’s job

was not to be objective and detached (as the

New York Times and

Wall Street Journal

aspired to be) but rather an eye-catching and loud tribune of the

people. In 1919, aided by the support of Colonel McCormack, Patterson

launched the

New York Illustrated Daily News, the nation’s first real tabloid, heavy on photographs, gossip and comics. Later shorted to the

New York Daily News,

the paper shocked even those used to the vulgarities of the “yellow

press” journals published by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer

by its relentless focus on sex scandals and photographs of leggy

models.

Patterson’s background as a playwright and novelist came through in

his editing of the comics, an art form he helped re-invent. Prior to the

First World War, comic strips were a bicoastal phenomenon, dominated by

artists based in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. This first

generation of cartoonist were all humorists or fantasists and their work

tended to episodic. Mutt and Jeff might have adventures that lasted for

a few weeks but these were always done in the spirit of burlesque.

Patterson nurtured a stable of cartoonists, most of whom were sons of

the Midwest, that took a different approach to comics. The Midwest

school of comics would be more story-based, more literary, more

melodramatic, and more realistic. The key members of the Midwest school

were Sidney Smith (

The Gumps), Frank King (

Gasoline Alley), Chester Gould (

Dick Tracy), Milton Caniff (

Terry and the Pirates) and, not least, Harold Gray.

Behind the Midwest school stood the looming figure of Gray’s first

mentor John McCutcheon. While primarily an editorial cartoonists,

McCutcheon was also know for his “boy’s stuff,” occasional panels that

he did that nostalgically reflected on his middle American childhood.

Unlike the raucous and violent humor of the Katzenjammer Kids,

McCutcheon’s work was quiet and ruminative, more mood pieces than

outright comedy. McCutcheon was one of the first newspaper cartoonists

to realize the value of simply recording everyday life as it happens,

without exaggeration. He had a profound impact on all his colleagues at

the

Tribune, including Gray.

If McCutcheon established the tone of the Midwest school, Sidney

Smith was its first nationwide hit. Working closely with Patterson,

Smith created

The Gumps in 1917. It started as a gentle spoof

of lower middle class life, with Andy Gump as the perpetual goat of a

father, dreaming of great wealth but never getting anywhere. His wife

Mim was the brains of the family, offering a reality check to Andy’s

futile schemes. At the prompting of Patterson, Smith made

The Gumps

into a story strip with elaborate cliff-hanger plots involving the

hapless family possibly inheriting a fortune from a mysterious uncle.

Both Smith and Patterson were good at spinning out melodramatic plot

lines reminiscent of Victorian novels. Readers of

The Gumps

loved following stories about court room intrigue, stolen inventions,

vamps who try to seduce rich old men, and pure girls who nearly marry

the scoundrels. Within a few years of its launch,

The Gumps became arguably the most popular comic strip in America. In 1922, Smith signed an unprecedented contract with the

Tribune

guaranteeing him a $100,000 a year for the next ten years, making him

much better paid than the president of the United States or any star

athlete of the era.

Harold Gray was a close witness to Sidney Smith’s spectacular success. Gray befriended Smith in the early days of

The Gumps. In 1920, Gray left the

Tribune

to start his own art studio and one of his first and most important

clients was Smith. Perpetually behind schedule, Smith needed an

assistant to help with the lettering and the Sunday strip. Gray proved a

capable and reliable lieutenant. The flowering of Gray’s art style,

which rapidly developed from the awkwardness of his undergraduate work,

took place under Smith’s tutelage. (Gray’s gratitude towards Smith can

be seen by the fact that he kept a signed photograph of Smith among his

personal papers, along with proofs of the Sunday Gumps he worked on).

There are many ways in which Annie is a child of

The Gumps.

The famous vacant eyes of Gray’s characters is a stylization borrowed

from Smith. The talkiness of Annie, the way the characters give

themselves over to long monologues, can be traced back in

The Gumps.

Even Gray’s forays into political commentary have a Gumpian origin:

Andy Gump was forever running for office, whether as a Congressman or

President.

More broadly, Smith created an art style that was taken over, often

in modified form, by all the Midwest cartoonists. The early comic strips

tended to be visually frantic, with the Katenzenjammer Kids or Happy

Hooligan running all over the place as bricks flew through the air and

dynamite blew up. Smith’s art was more static and character-based. He

emphasized heads and hands of his characters (which were slightly larger

than life). What counted was not so much how characters moved but their

facial expressions. Characters gave each other a lot of space in

Smith’s strip: they often stood apart, surrounded by an invisible halo.

The background of Smith’s work was equally sedate: a drab suburban house

or a nondescript building was all he would give reader. This “less is

more” approach actually worked very well for the type of long narratives

Smith did and it was widely copied. If you look at King, Gray, or Gould

closely, you’ll see that they all studied Smith with care.

Of course, no one origin story can completely

explain Annie: the character was based heavily on everything Gray

experienced up to that point.

The early 1920s were a time for Gray to consolidate his life before

making his big push for cartooning stardom. Taking informal cartooning

lesson from Smith and earning a good salary with his commercial art

study, Gray was ready to settle down. On October 22, 1921 he married

Doris C. Platt, a frail young school teacher. In her many journeys,

Annie would often meet kind-hearted delicately faced young school

teachers (Mrs. Pewter, introduced in late 1927 is the first of the

breed) and Doris seems a likely model for them. (In the June 11, 1925

strip Gray introduced a joke about his wife’s family by having Byron

Silo seek the help of the attorney George Platt). We catch a hint of

Gray’s newly married happiness in the Christmas card he designed in

1921, which has valentine hearts everywhere.

Married and learning his trade working for the most successful

cartoonist in America, Gray was ready to make his move. Starting in

early 1924, he was constantly coming up with ideas for comic strips and

pitching them to Captain Patterson. Frustratingly, the editor kept

rejecting them. It’s hard to know exactly how Gray came up with Little

Orphan Annie, since there are several conflicting accounts of her

origin. After Patterson died, Gray offered up one more origin story, one

that left the publisher out of the picture. In this version, Gray

struck up a conversation with a young street urchin he met while roaming

the streets of Chicago looking for ideas. “I talked to this little kid,

and liked her right away,” Gray told

Editor and Publisher in

1951. “She had common sense, knew how to take care of herself. She had

to. Her name was Annie. At the time, some 40 strips were using boys as

the main characters; only three were using girls. I chose Annie for

mine, and made her an orphan, so she’d have no family, no tangling

alliances, but freedom to go where she pleased.”

Of course, no one origin story can completely explain Annie: the

character was based heavily on everything Gray experienced up to that

point, including the books he read and the movies he watched. Gray as a

voracious reader of Dickens and there is a great deal of the Victorian

novelist in Annie. “You can take Great Expectations or any Dickens’ book

and put in running water and a telephone and you have Annie in a modern

setting with a sound story,” Gray told an interviewer in 1938. Annie

herself on several occasions extolled the virtues of Dickens. Dickens’s

fiction is rife with orphans, lost children who roam the city streets,

sudden reversals of fortune with characters finding and losing money

rapidly, coincidental meetings, corruptly-administered institutions like

orphanages, hypocritical old people who pretend to be charitable but

are only interested in their own personal self-aggrandizement,

benevolent rich men who provide last minute rescue to those in jeopardy,

and many other motifs that would be recycled in

Little Orphan Annie.

“Children love her—adults sigh for their own lost spontaneity and initiative of youth, seeing them in her.”

Dickens was a natural patron saint and precursor for the comic strip

business: aside from Gray, Frank King and George Herriman (the creator

of Krazy Kat) were also voracious readers of the Victorian novelist.

Many traits made Dickens an attractive aesthetic model: his novels were

originally serialized, thus offering hints on how to tell continuous

stories in small installments. Dickens worked closely with illustrators,

making his novels a form of proto-comics. As a writer, Dickens was

noted for his ability to create vivid, memorable characters, a skill

that led to the accusation that he was a caricaturist (which is, of

course, another way of saying he was a cartoonist).

Dickens was not just a popular novelist, he was also a cultural

populist, a writer who was unembarrassed in sharing the taste of the

masses for sentimental melodrama and celebrating the lives of ordinary

people. Harold Gray in the 1920s was an artist in this mold: in his

politics and taste he was very much a populist, championing the cause of

the struggling little man and woman. Gray’s populist taste comes

through in his favorite foods (he was a steak and potato man) and his

preference for American entertainers like Bert Williams over European

classical music.

In addition to Dickens, there was a vast array of Victorian and

post-Victorian fiction and poetry that Gray took inspiration from. In

his hurly-burly plots we can see elements of East Lynne, Over the Hill

to the Poorhouse and Pollyanna. Many of these stories had been adapted

on stage and in the early movies, which formed another layer of

influence. Looking at Gray’s character design and the way his people

move, it’s hard not to be reminded of silent movie melodramas, with

their emphasis on histrionic action: characters in Gray are always

grimacing, leering, or pointing their fingers, all actions taken from

the theatrical tradition.

Gray and Captain Patterson had a fruitful but contentious

relationship. They would later argue the direction of the comic strip

and about money (after the publisher died, Gray painted an unflattering

picture of him in a sequence where a cartoonist is frustrated by a

credit-hogging blowhard of a boss). In the early days of the strip, the

chief argument was over Annie’s fate: Gray wanted to keep her as the

daughter of Warbucks while Patterson thought it was better to keep her

poor. The inspired solution was to split the difference. Annie would

stay with poor couples for half the strip but when necessary “Daddy”

Warbucks would rescue her. Of course, this meant that “Daddy” would

often have to disappear or seem to die, but these recurring plots

actually strengthened, the thematic basis of the strip: Annie was an

orphan not once but many times over as her “Daddy” kept vanishing.

On October 27, 1925, the

Tribune published an issue without

Annie. This seems to have been done deliberately, a ploy on Patterson’s

part to test the appeal of the strip. What it proved was that Little

Orphan Annie had an immense fan base: readers inundated the newspapers

with complaints. One especially perceptive letter from Minnie McIntyre

Wallace is worth quoting:

Dear Mr. Gray,

You have achieved rainbow’s end when your

creation, Orphan Annie, was made the subject of a column of front page

stuff. It is always pleasant to know that merit is recognized. Annie is

certainly popular and I want to give you my version of why she has made

such a hit.

First—because she is the voice of the

people; second, because she is democratic in the true sense of the word,

warm of heart, sympathetic, strong for the underdog; third, because she

is not dazzled by wealth or shoddy gentility; fourth because she is the

eternal child that lives in the hearts of men and women; fifth, because

one never knows down what lane she will run next; sixth, because she

loves animals and nature, bees and buds and berries and bossy cows.

Children love her—adults sigh for their own lost spontaneity and

initiative of youth, seeing them in her.

*

All of Gray’s hard work was not paying off: his career was well launched.

Yet this triumph was blighted by tragedy as Doris Platt Gray, after a

long illness, died on November 22, 1925. There is a remarkable echo of

this painful experience in the strips that Gray was working on while his

wife was in her final illness, strips which ran just days following her

funeral. In these strips Mrs. Warbucks leaves her husband. Normally a

pillar of ramrod strength, “Daddy” falls to pieces and becomes catatonic

as he thinks about his departed wife. As Annie notes, “Daddy doesn’t

say a word, hardly.” (Dec. 9, 1925). Eventually, “Daddy” is rescued from

his emotional meltdown by the fact that he realizes he still has

something to live for: his duties of taking care of Annie. In future

episodes, those who lose loved ones throw themselves into work, finding

that constant activity is the best therapy for grief. Did Gray also

discover that looking after Annie, drawing her daily adventures, gave

him comfort in the aftermath of loss?

There is a further personal issue that seems connected with the

strip. Harold and Doris Gray didn’t have children. When he remarried in

1929, Gray had a second relationship that was happy but childless. In

her early adventures, Annie constantly meets couples that wanted to have

children but couldn’t: the Warbucks, the Silos, the Flints (who had a

daughter who died). “Youngsters were denied us,” Warbucks stoically says

about his marriage. The silent pathos of barrenness is a strong theme

in the early strips. Perhaps because he didn’t have any real life

children, Gray would devote his life to his imaginary creation. Like

Annie, Harold Gray knew that life was filled with trials and it’s best

to soldier on with a chipper attitude.