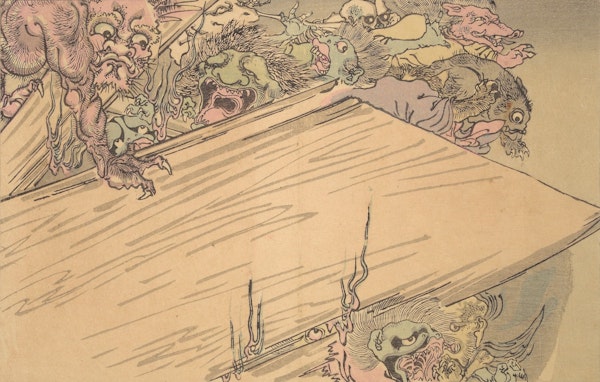

Kawanable Kyōsai’s Night Parade of One Hundred Demons (1890)

Kawanabe

Kyōsai (1831–1889), aka “The Demon of Painting”, composed this book of

woodblock illustrations toward the end of a life that had begun during

the Edo period, when Japan was still a feudal country, and ended in the

midst of the Meiji period, when the country was transforming into a

modern state.

Kyōsai

was by all accounts the bad boy artist of his era. Considered both

Japan’s first political caricaturist and one of the first authors of a

manga magazine (Eshunbun Nipponchi), Kyōsai was arrested by the shogunate three times for his commitment to free expression. Also, he made no secret of his love for sake.

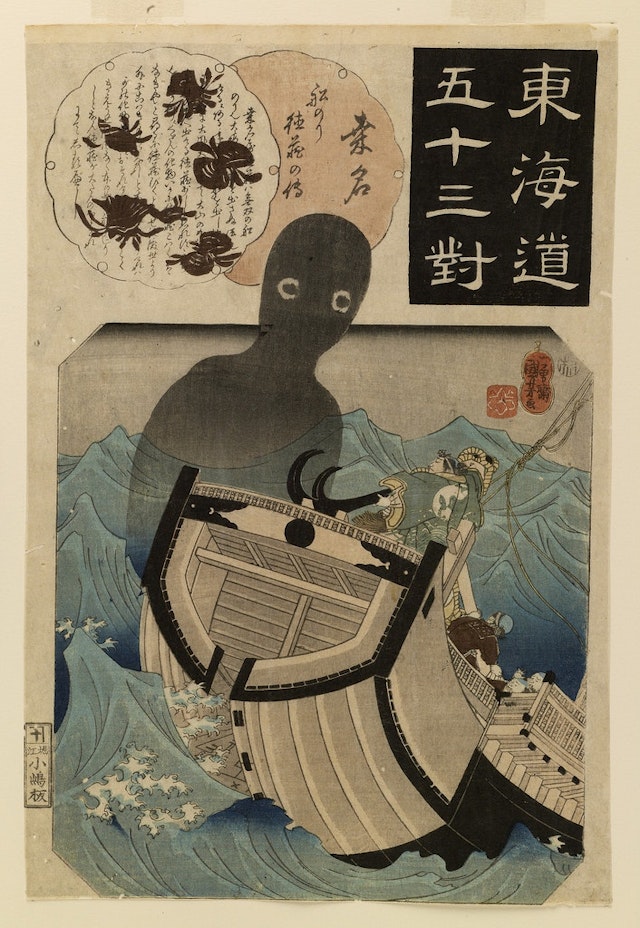

Kyōsai’s

version was, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art which houses

the book, one of the artist’s most popular volumes, offering “a

spectacular visual encyclopedia of supernatural creatures of premodern

Japanese folklore”. (To see more examples of such supernatural

creatures, also see our post on this Edo-era scroll.)

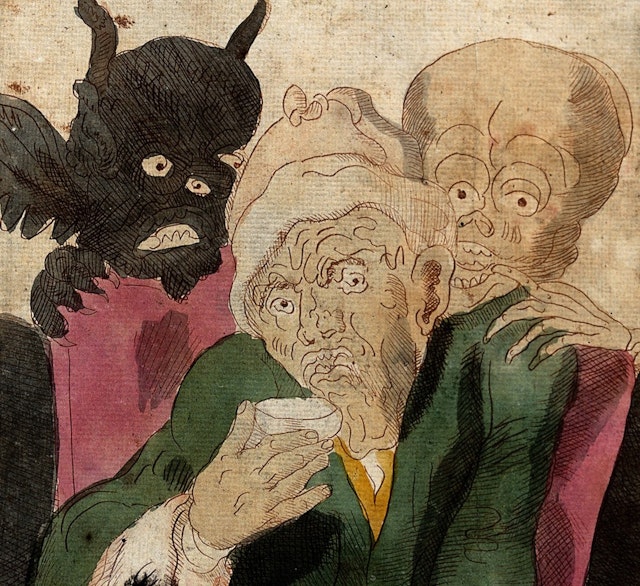

One

can see why it was so popular. Narratively, it paves the way for the

fantastic parade with two woodblocks: the first depicts a group of

adults and children gathered around a coal fire to hear ghosts stories,

the second a man (probably Kyōsai) setting down his calligraphy brush

and extinguishing the lamp in preparation for the night in which the

demons will appear.

Each

double-page of the book is arranged in such a way as to join up with

the next, as though a continuous scroll is divided over the pages of a

book. Though be aware that, of course, the book is bound on the right

and so runs counter to the usual left-to-right of English-language

books, and so also counter to how our gallery below is set up to

display!

Medium

Epoch

Tags

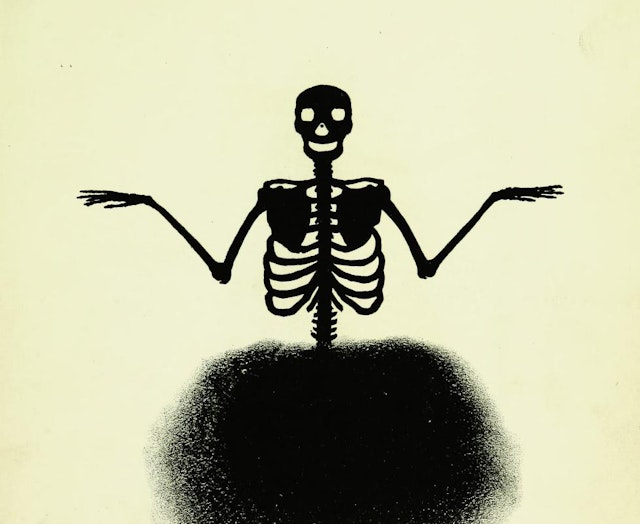

Skeleton soldiers, a horse with the head of a man, and other monsters advance in the growing darkness.

A

one-eyed, malformed goddess, Benzaiten, is accompanied by an elephant,

reptilian monsters, and, at left, the fierce Buddhist guardian Fudō Myōō

holding a sword.

Ritual implements such as a monk’s fly whisk, boots, and a Buddhist gong become monsters.

Musical instruments, a lute (biwa) and zither (koto), appear as monsters.

At

right, a demon with a large nose and wings (tengū) carries panpipes

(shō) and a pilgrim’s staff. His servant follows in wooden clogs (geta),

with a wolf-like head and gaping mouth.

A

helmet for a court dance (bugaku), a chime (kei), ritual scepter

(nyoi), and a folding fan turn into flying and running demons.

At right, a monster grips a feathered spear. An ogre follows, wearing a nobleman’s cap (eboshi) and carrying a similar spear.

At

left, a small demon riding a badger with a stirrup on its head follows a

hairy headed demon and at far right, a shrouded, furry animal.

At right, a horned demon bears a spiked spear. At left, a beaked demon wields a wooden mallet over a one-eyed red demon’s head.

At

left, a monster holds up a mirror for an Otafuku-esque ghoul to apply

black dye to her teeth. At right, a chubby faced figure carries a bag

beside a three-eyed ghoul.

Animal

demons, including one resembling a mad Shinto priest, carouse on an

enormous bolt of cloth. A clawed monster hides underneath.

At

left, a beaked demon holds an umbrella monster, followed by a rope

monster riding a hobbyhorse, and a hairy monster with a long, horned

snout (kirin).

Everyday kitchen utensils such as lids, pots, and trivets have turned into monsters.

Demons emerge from a large, wooden chest.

Monsters,

including a badger wearing a courtier’s cap, carry Buddhist ritual

implements, such as a magical scroll inscribed in Sanskrit, at far

right.

Several monsters, continue the procession, including one with a Buddhist monk’s alms bowl on its head.

A row of demons, some with banners, another with a gourd-like head, march forward.

A group of rowdy ghouls appears, including, at far right, a demon in a red robe with a hand scroll.

At

right is the demon Nurarihyon, in the guise of an old man with a huge

head and Buddhist rosary. He is followed by rodent-like monsters.

Frightening beasts have features, from left, of a hag, an elephant, and a rabbit.

A

green dragon chases demons, including a winged hag, at right, who is

embracing a tiny creature. Below, a pink one-eyed monster wears a grass

skirt.

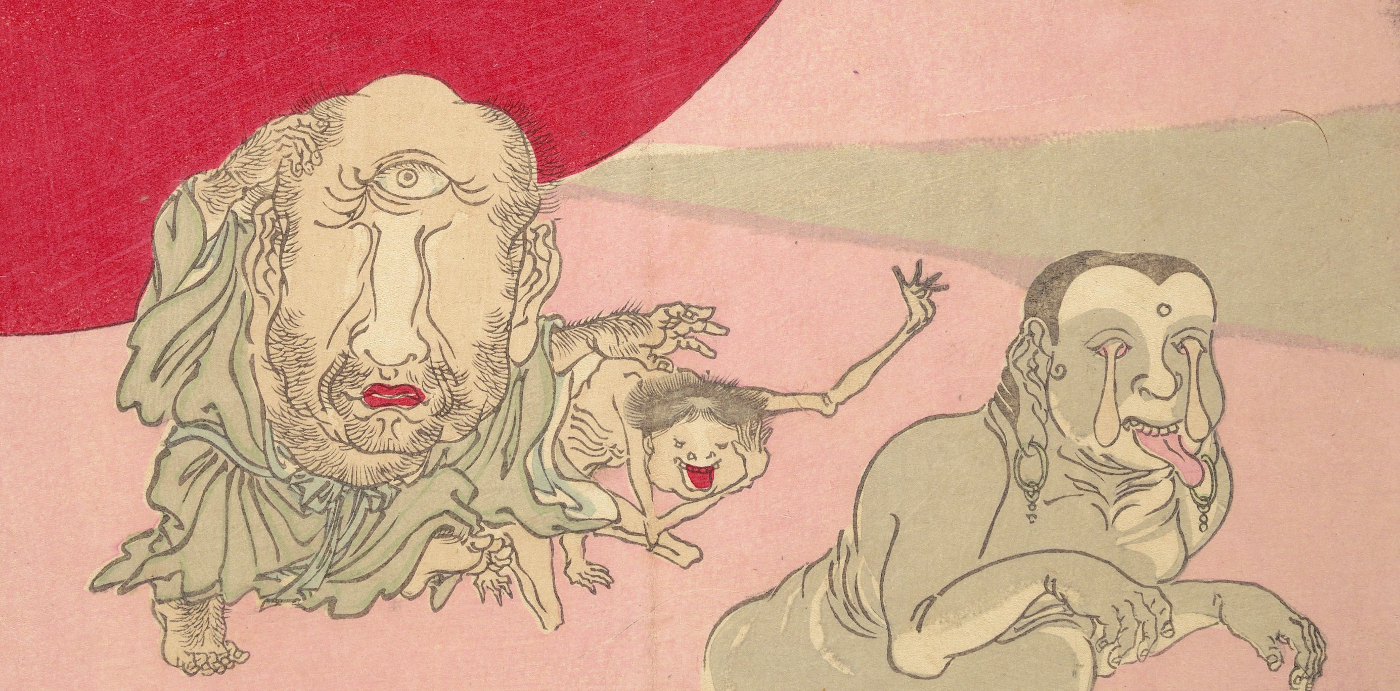

Under

dawn’s red sun, the parade of demons ends. From left: the one-eyed

Aobōzu, who kidnaps children, a water dwelling creature (kappa), and

Nuribotoke, a Buddha-like demon with dangling eyeballs.

https://www.earthlymission.com/if-the-planets-were-as-far-away-from-earth-as-the-moon/

https://www.earthlymission.com/if-the-planets-were-as-far-away-from-earth-as-the-moon/