2/24/2021

2/23/2021

Louis XV’s Most Beloved and Most Hated Mistresses

France

in the mid 18th century was a time of romantic dresses and powdered

wigs. Kings on tall horses clapping down cobblestone streets. The time

of Voltaire and Rousseau, of Renaissance fading into Rococo.

France

in the mid 18th century was a time of romantic dresses and powdered

wigs. Kings on tall horses clapping down cobblestone streets. The time

of Voltaire and Rousseau, of Renaissance fading into Rococo.

It was a time of the “haves” and the “have nots.” Of the 26 million people living in France, over 21 million were peasants. The remaining few were the rich, the nobility, and a handful of clergy.

Life was brutal if you were a peasant. Working land they didn’t own to keep some small portion to sustain themselves. Paying the outrageous taxes that would eventually lead to revolution. Taxes the nobility were exempt from.

They were the weary, unwashed masses and they worked from dawn to dusk to support the lifestyle of the rich and noble.

Whether rich or poor, women were passive citizens. Men made decisions for women, whether they were fathers or brothers. Later, her husband. If you were rich or a noble, education meant gentle pursuits. If you were a peasant, education meant learning how to be a good wife and mother.

The life of a peasant woman made life at the court appealing. A position as queen’s handmaid, governess to the royal children, or even the king’s mistress was a gentler life than a peasant’s life of toil and taxes. Many mothers would move mountains to achieve a court position for their daughters. It was rare to have such an opportunity, and even more rare for it to end well…

Louis XV, the toddler king…

Like Henry VIII, Louis XV was not born to be king. The second-born grandchild of the beloved Sun King, he was fourth in line to the throne, behind his uncle, his father, and his older brother.

However, it was an era of poor medical care, poor hygiene, bloodletting, and too often, people died of diseases we seldom die from today. Death doesn’t discriminate between rich and poor when it taps on the window.

Before Louis was one, his uncle died of smallpox. Before his second birthday, his father, mother, and brother died of measles. Just a toddler, Louis XV was the only family member to survive measles, and only because his governess would not permit the doctor to perform bloodletting on the toddler.

At age two, the only surviving male, he became heir to the throne. At five, his grandfather died and Louis became the toddler king. Advisors ran the country until Louis assumed the throne at age 13.

Married at fifteen…

When Louis turned 15, he married Maria Karolina Leszczyńska, daughter of the deposed king of Poland. The couple met on the eve of their marriage and it was said to be love at first sight. Two years later, Maria had twin girls and Louis was over the moon at his tiny twin daughters.

For almost a decade, the kingdom had a loving king and queen and a bounty of royal babies to celebrate. The two were deeply in love and inseparable, and Maria delivered ten children in ten years.

Miscarriage and mistresses…

After ten good years, it all fell apart. The queen miscarried her eleventh pregnancy and the royal doctor told her she was not permitted to have marital relations. Louis moved out of the marital chambers, into separate quarters.

Whether fate, bad timing, or bad character, while the king and queen were sleeping separately, Louis met Louise de Mailly-Nesle, a lady in waiting to his wife. Soon, she was sneaking into his chambers at night.

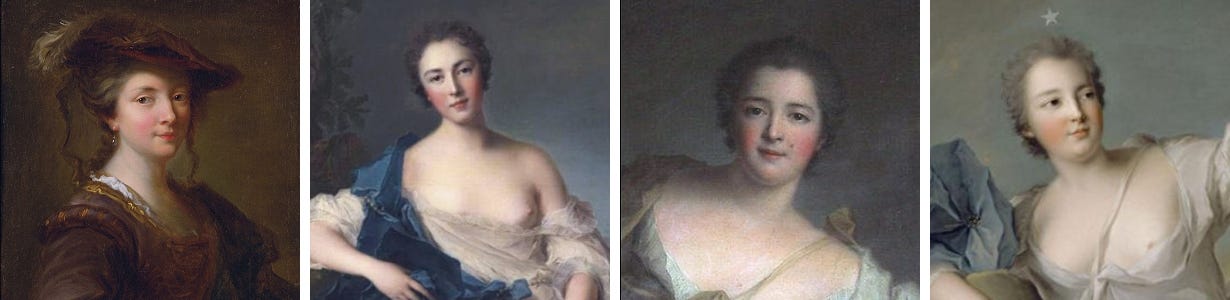

The young king was 25 years old and had been married since 15. Suddenly, he discovered the court was a buffet of beautiful women. Lady Louise, it turned out, had lovely sisters. Over the next few years, he would have four of the five de Mailly-Nesle sisters as his mistresses.

He abandoned Louise for her sister Pauline until she died delivering his stillborn child. He cut short his affair with Diane, the third sister, when he met their youngest sister. Marie Anne was able to negotiate financial compensation and was given an income to live on.

A national embarrassment…

The de Mailly-Nesle sisters were just the beginning, and Louis was not known to be discreet. He didn’t have to be, he was the King.

Eventually, the church stepped in. They insisted that he was a national embarrassment to the throne and country. They wanted him to attend confession for the sin of adultery. Instead, he stopped taking the sacrament and continued his dalliances with the women of the court.

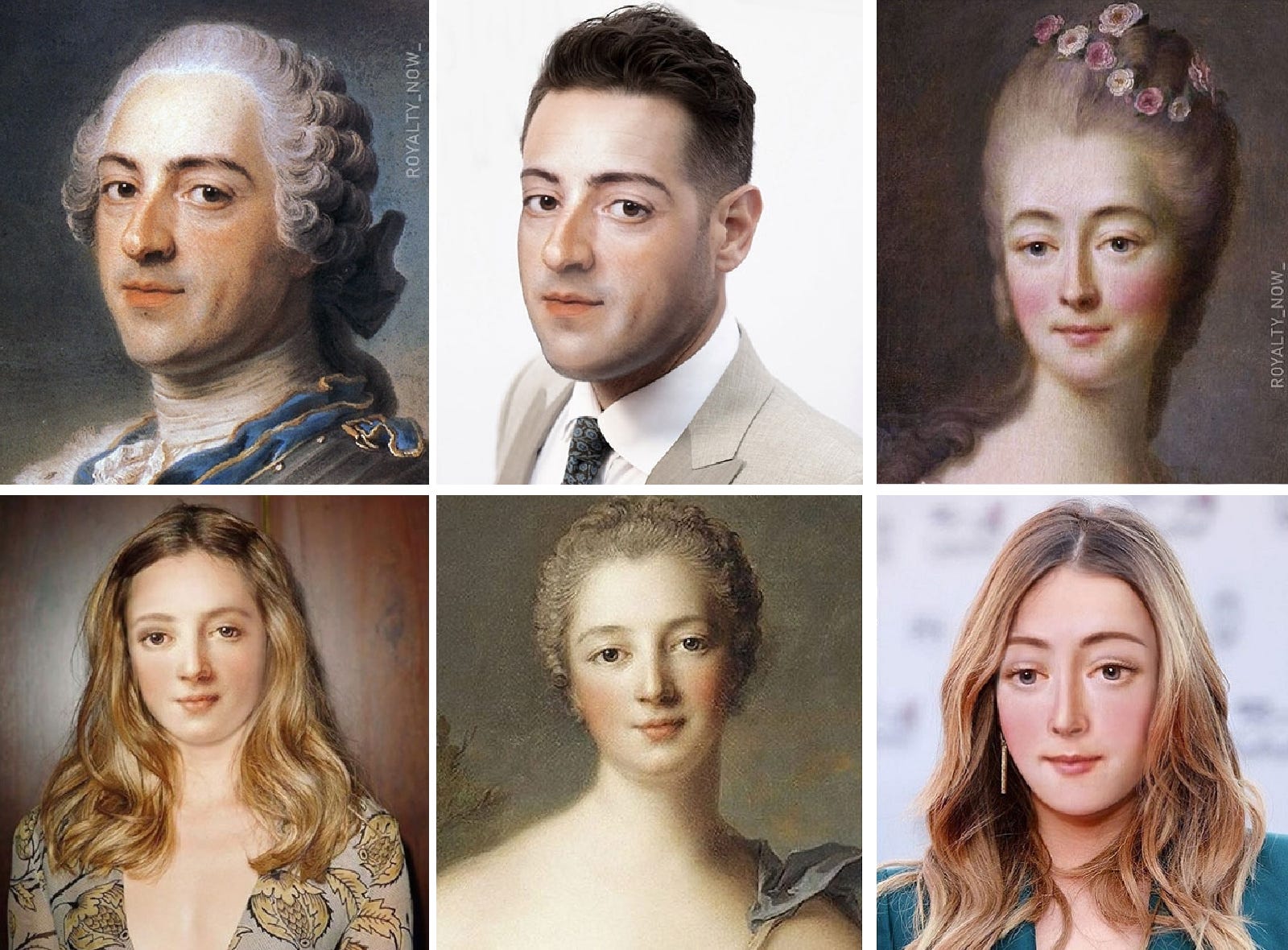

The playboy king’s most loved and hated mistresses and what they would look like today

Ultimately, he would have sixteen mistresses. Two would bear illegitimate children, making him a father of twelve. Most would be largely ignored by history and historians. Minor players in the life of a playboy king.

Two did not fade into history but became as memorable as the king himself.

The most loved — and the most hated.

Once again, artist Becca Saladin has applied her photoshop magic to show us what they would look like if we met them today. As she explains:

“the work is worth it to make history come alive and these great historical figures more relatable.” — Becca Saladin

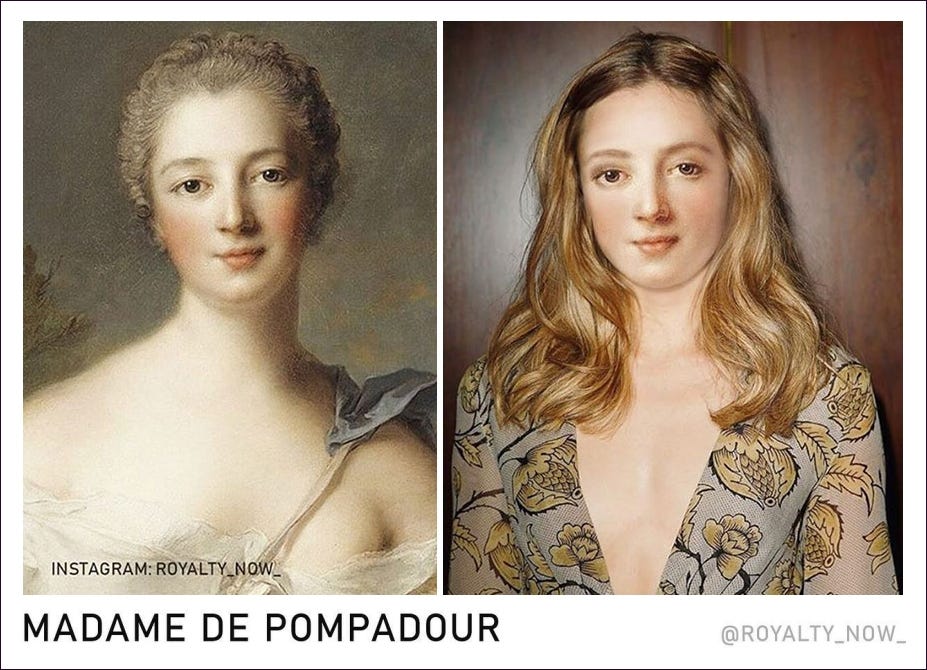

Madame du Pompadour: Louis meets the one…

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson was a member of the French court. She was not born a noble, but she was raised in a wealthy household. When she was a little girl, her mother took her to a fortune-teller who said the child would one day reign over the heart of a king. Excited, her mother ensured that the girl received a private education and was primed for a life in the court.

Louis first spotted her at a masked ball.

It was love at first sight.

Known as Madame du Pompadour, they were together for twenty years. She was no ordinary dalliance. Pompadour promptly took charge of his schedule, became his aid, advisor, and a powerful political partner. She adopted the role of the prime minister, contributed to domestic and foreign politics, and became the most powerful woman in the French court.

Madame du Pompadour was intelligent, kind, and more outgoing than the self-secluded queen. She was a generous patron of the arts who played a key role in making Paris the capital of taste and culture in Europe. She was also creative. A stage actress, gem engraver, artist, and amateur printmaker.

Louis XV was utterly devoted to her until she died of tuberculosis at age 42. After her death, Voltaire penned a note to the King;

“I am very sad at the death of Madame de Pompadour. I was indebted to her and I mourn her out of gratitude. It seems absurd that while an ancient pen-pusher, hardly able to walk, should still be alive, a beautiful woman, in the midst of a splendid career, should die at the age of forty two. “ — Voltaire

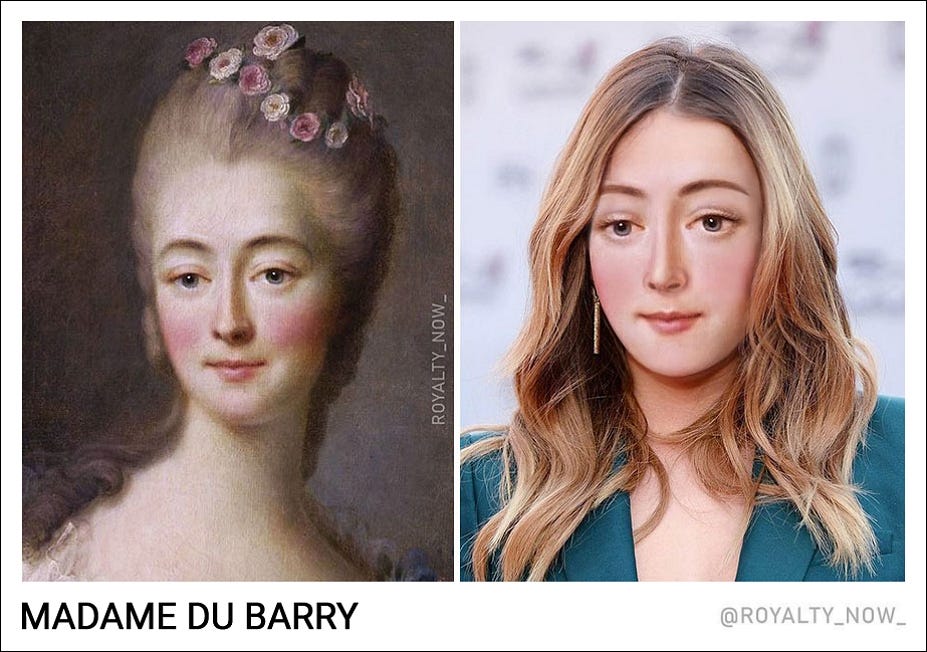

Madame du Barry: the most hated woman in France

Jeanne Bécu, better known as the infamous Madame du Barry, was the woman who pulled Louis out of the black pit of despair he’d fallen into.

First, he’d lost his beloved Madame du Pompadour. Then, while grieving her death, his son contracted tuberculosis and died.

Death was not done with the court. The queen became inconsolable at losing her son. To make matters worse, her father died right after her son, followed by the death of her beloved daughter-in-law. Staggering under the losses, Queen Marie fell ill and died. Louis had to bury his queen, too.

It was as though death wrapped a cold hand around the palace and Louis fell into a pit of despair. He was not young anymore. In his late 50s, he was devastated by the string of losses.

Enter, Jeanne Bécu: Louis XV’s most hated mistress

Jeanne Bécu was born into poverty. Of the servant class and out of wedlock, at that. Her mother, Anne Bécu, was a lowly seamstress. Her father was believed to be a friar, though it was never confirmed.

As a child, she was left at a convent to be educated. At 15, she left the convent. With no prospects and no father to provide for her, she told trinkets in the streets until she found work in a haberdashery shop named ‘À la Toilette’.

Historians say she was one of the most beautiful women in France. She had thick blonde hair that fell into natural waves, wide blue eyes, perfect porcelain skin, and a physique that never failed to turn heads.

One day, the young beauty caught the attention of Comte Jean Baptiste du Barry, a high-class pimp who owned a casino. Du Barry spared no time in making Jeanne his mistress and gave her the name Madame du Barry.

At first he “introduced her” to many aristocratic men, but he quickly realized that if he played his cards right, he may be able to influence the king through the young beauty, and off she was sent to the castle.

The king was smitten instantly.

The court was horrified.

The first favor she asked of the king wasn’t for money or gifts. It was for mercy. She became known for saving people from execution; falling to her knees until the king agreed to cancel executions and spare lives.

It didn’t matter. She didn’t belong.

She was 33 years younger than the king. From the servant class! Gold digger, they called her. The king’s whore. A guttersnipe. At least the other mistresses “belonged” at the court. She did not. The women of the court were irate that this strumpet had been chosen as mistress over noble-born ladies.

Her biggest rival was Marie Antoinette, the 14-year-old princess engaged to the king’s grandson. Antoinette and du Barry first met on the eve of Antoinette’s wedding and it was hate at first sight.

When Antoinette was informed that du Barry’s role in court was to pleasure the king, she was disgusted and refused to speak to her. The snub rippled through the court and du Barry became the most hated woman in France.

Hated for being of the servant class, hated for being illegitimate, and hated for her scandalous past at the hands of a pimp that saw her beauty as profitable. “A cheap whore that got lucky,” they called her.

And yet, the four years of her tenure as official mistress of the king were the best years of her life. She was never hungry. She slept in grandeur, drank chocolate for breakfast, and had closets full of lovely clothing and jewelry.

Four years later, when Louis XV died of smallpox Marie Antoinette and her husband became king and queen of France. Madame Du Barry was publicly disgraced and banished from the Court.

Written by

2/19/2021

15 mots japonais

Dépaysement, affriolant, retrouvailles, emberlificoter… Ces mots sont banals pour n’importe quel francophone. Pourtant, pour les étrangers, ils sont diaboliques, car ils ne possèdent aucun équivalent dans aucune autre langue de la planète. Mais l’inverse est aussi vrai : chaque langue possède un vocabulaire bien à elle, qui transcrit une manière de voir le monde, une géographie ou une culture, et qui ne trouve pas de traduction directe ni exacte. Ces mots exotiques qui expriment en à peine quelques syllabes ce que le français ne parvient à dire qu’en une ou plusieurs phrases sont des casse-tête pour nos traducteurs, mais des trésors pour les amoureux des voyages.

Le sens aigu de l’esthétisme, la sensibilité à la nature, aux émotions et aux petits plaisirs de la vie, mais aussi l’importance de la maîtrise de soi… Le japonais, parlé par cent trente millions de personnes dans le monde et écrit avec des kanjis (sortes d’idéogrammes), des katakanas et des hiraganas (espèces de signes phonétiques), offre une infinité de nuances difficiles à cerner pour un étranger. Voici quinze mots retranscrits en rōmaji (alphabet latin), et qu’on aimerait bien adopter dans la langue de Molière.

Tsundoku : ce terme désigne cette manie compulsive d’acheter des livres qu’on n’aura pas le temps de lire, et qui vont donc juste s’entasser dans la bibliothèque.

Mono no aware : à la fois esthétique et spirituel, ce concept renvoie à cette douce tristesse que l’on ressent lorsque l’on prend conscience de la fugacité des choses de la vie. S’applique par exemple à la floraison des cerisiers, que les Japonais apprécient d’autant plus qu’elle ne dure guère. C’est une sensibilité pour l’éphémère, en quelque sorte.

Irusu : caractérise le fait de se faire le plus discret possible et de prétendre ne pas être chez soi lorsque quelqu’un sonne à la porte.

Komorebi : l'attention que portent les Japonais aux plus infimes beautés de la nature s’exprime à merveille avec ce mot faisant référence à la lumière du soleil qui filtre à travers les feuilles des arbres.

Age otori : expression très utile, qui pointe cette désagréable sensation que l’on éprouve parfois en sortant de chez le coiffeur : celle d’être plus horrible après qu’avant !

Kawaakari : ce mot s’applique aux reflets particuliers que peut prendre l’eau au crépuscule ou une fois la nuit tombée, par exemple le miroitement de la lune sur l’onde d’un lac ou d’une rivière.

Yoko meshi : littéralement, pourrait se traduire par "avaler de travers". Mais cette formule fait en réalité référence à cette montée de stress qui peut nous étreindre quand nous sommes contraints de parler une langue étrangère, cette indescriptible angoisse de ne pas réussir à comprendre et/ou à se faire comprendre.

Baku shan : un mot plutôt cruel, puisqu’il sert à qualifier une femme considérée comme plus jolie de dos que de face.

Natsukashii : cet adjectif s’emploie lorsque le passé refait brusquement surface, via un objet, un souvenir, une mélodie… Mais attention, aucune peine n’est ressentie : ce qui est natsukashii rend nostalgique, mais sans regret, plutôt avec bonheur.

Kyōiku mama : correspond à une mère qui exerce une pression et un contrôle excessifs sur ses enfants en matière d’études et d’orientation professionnelle. Clairement péjoratif.

Shoganai : pourrait être plus ou moins traduit par "il n’y a rien à faire". Mais ce mot renvoie en réalité à toute une philosophie de l’existence, fondée sur l’importance de l’acceptation : les Japonais l’utilisent pour remonter le moral de quelqu’un qui connaît un épisode difficile en lui signifiant qu’on ne peut pas tout contrôler dans la vie, que parfois, certaines choses négatives adviennent sans qu’on n’y puisse rien. S’inquiéter, culpabiliser ou regretter n’a alors aucun sens. Shoganai est donc une espèce d’incitation au détachement.

Boketto : ce nom exprime le fait de regarder distraitement au loin, signe qu’on est physiquement présent, mais mentalement absent.

Arigata meiwaku : désigne l’aide offerte par quelqu’un sans qu’on lui ait rien demandé. Une initiative qui peut s’avérer totalement contre-productive, et pour laquelle on se sent, malgré tout, obligé d’afficher sa reconnaissance. En résumé, c’est une bonne intention… indésirable !

Koi no yokan : c'est une sorte de prémonition amoureuse. Toutes ces sensations exaltantes que l’on ressent lorsque l’on rencontre pour la première fois quelqu’un dont on devine que l’on va, immanquablement, s’éprendre. Pas tout à fait le coup de foudre, mais déjà une ébauche de passion.

Tatemae : un concept fondamental dans la culture nippone, que l’on pourrait traduire par "façade". Tatemae, c’est ce que l’on laisse transparaître de soi-même en société, les opinions et les sentiments que l’on ose exposer en public. Cette position consensuelle, adoptée en général pour éviter de faire des vagues ou de froisser un tiers, ne peut donc pas forcément toujours correspondre à ce que l’on pense ou ce que l’on désire réellement, qui se traduit par honne. Le paraître versus l’être, en quelque sorte.

© PRISMA MEDIA 2018 TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉSLOST IN TRANSLATION. Chaque premier lundi du mois, GEO vous invite à découvrir un petit lexique de mots intraduisibles aussi savoureux que dépaysants. Aujourd’hui, direction le Japon.

2/18/2021

Chandler's feud with Alfred Hitchcock

Why Did Raymond Chandler Hate Strangers on a Train So Intensely?

Chandler's feud with Alfred Hitchcock had a special venom, but why?

Raymond Chandler had a complicated relationship with Hollywood. If you’re inclined to dig around there are any number of interesting and sometimes shocking anecdotes about his time working around movies, and he certainly left behind a litany of quips on the subject. (“Its idea of ‘production value’ is spending a million dollars dressing up a story that any good writer would throw away.”) My own personal favorite has a slightly lighter air than most of the matter on offer. It’s the now legendary, possibly apocryphal story about William Faulkner, hired for a script adaptation, desperately trying to work out the plot of The Big Sleep and inquiring of Chandler which of his characters killed Sternwoods’ chauffeur, to which Chandler replied, “I don’t know.” There’s a lesson in there for writers. Not necessarily a good or coherent lesson, but it just may get you through a few difficult days wrestling with a work in progress.

But there’s a slightly more bitter feud that’s always gripped my imagination. In 1950, Alfred Hitchcock, after failing to secure Dashiell Hammett’s services, approached Chandler with the job of adapting Strangers on a Train, a debut novel by the then-unknown Patricia Highsmith. The concept was a stroke of dark genius: two men, meeting on a train, agree each to commit a murder on the other’s behalf. Chandler took the job and after some consultation with the director went about writing a first draft of the script. Hearing little to nothing from Hitchcock, he took a stab at another version and sent that one along, too. Remember, at this time, Hitchcock was fairly celebrated, but not yet the master of suspense, Hollywood titan he would later become. He had made Rebecca, Notorious, and other admired films, but we’re still in the period before his masterpieces here, before Dial M for Murder, Vertigo, The Birds, Psycho and the rest. Surely Chandler knew that he was working with a skilled craftsman, but maybe we can allow that he believed himself worthy of at least a considered response from the man who hired him to do all that work.

Well, that wasn’t to be. Chandler never heard back from Hitchcock about the scripts he’d commissioned. In fact, Hitchcock had taken the drafts and, as he was want to do, quite famously in later years, arranged for a complete dismantling and evisceration of the work performed to date. Pretty standard Hollywood, you might argue, and you’d probably be right. But this is Chandler we’re talking about. A trembling wire of brilliance and resentment. Late in the year, Chandler was able to arrange a screening of the film, ultimately made from the script by Czenzi Ormonde. Ormonde was the protégée of Ben Hecht (renowned as the “Shakespeare of Hollywood”). The screening, well, it left Chandler pretty hot. Not the good kind of hot. After stewing on the matter for a while, he decided to write to Hitchcock, his one-time supposed employer, whom he addressed affectionately as “Dear Hitch,” then proceeded to lambast in utterly Chandler fashion.

Are Chandler’s objections warranted? Probably not. Strangers on a Train, released the following year, has generally been recognized as a classic of the form. It launched Hitchcock into a new stratosphere of acclaim and helped make Highsmith into a celebrity, though she didn’t much care for the movie herself.

Whatever you think of film’s bona fides, you might also admire the little bits of poetry Chandler dripped into his poisoned pen letter to Hitchcock. That letter, swinging wildly between self-effacement and grandiosity, understanding and condemnation, imploration and outright insult, is really a marvel.

Here’s the missive, in full:

December 6th, 1950

Dear Hitch,

In spite of your wide and generous disregard of my communications on the subject of the script of Strangers on a Train and your failure to make any comment on it, and in spite of not having heard a word from you since I began the writing of the actual screenplay—for all of which I might say I bear no malice, since this sort of procedure seems to be part of the standard Hollywood depravity—in spite of this and in spite of this extremely cumbersome sentence, I feel that I should, just for the record, pass you a few comments on what is termed the final script. I could understand your finding fault with my script in this or that way, thinking that such and such a scene was too long or such and such a mechanism was too awkward. I could understand you changing your mind about the things you specifically wanted, because some of such changes might have been imposed on you from without. What I cannot understand is your permitting a script which after all had some life and vitality to be reduced to such a flabby mass of clichés, a group of faceless characters, and the kind of dialogue every screen writer is taught not to write—the kind that says everything twice and leaves nothing to be implied by the actor or the camera. Of course you must have had your reasons but, to use a phrase once coined by Max Beerbohm, it would take a “far less brilliant mind than mine” to guess what they were.

Regardless of whether or not my name appears on the screen among the credits, I’m not afraid that anybody will think I wrote this stuff. They’ll know damn well I didn’t. I shouldn’t have minded in the least if you had produced a better script—believe me. I shouldn’t. But if you wanted something written in skim milk, why on earth did you bother to come to me in the first place? What a waste of money! What a waste of time! It’s no answer to say that I was well paid. Nobody can be adequately paid for wasting his time.

—Signed, ‘Raymond Chandler’

***

“Written in skim milk.” When did you ever read a more withering piece of criticism?

Why did Chandler hate Strangers on a Train so intensely? We can puzzle over the letter, searching for answers, and I have. I imagine what it comes down to is this, the movie wasn’t his. Chandler, especially later in his life, was an unforgiving correspondent and often cruel. Shortly after this time, he would begin work on The Long Goodbye. In my view, it’s his greatest work, maybe the greatest crime novel ever written, and it may also be his most disenchanted. There’s a deep, rich vein of resentment running underneath it. In that late world of Marlowe and Terry Lennox, Los Angeles has a special kind of stain on it.

I don’t know if this sordid little episode with “Hitch” had anything to do with The Long Goodbye, but I’d like to think so. In any case, that’s one hell of a letter. Petty, nasty, and possibly wrong, with glimmers of genius.

Flannery O’Connor’s Mayonnaise and Her Mother

Flannery O’Connor’s Two Deepest Loves Were Mayonnaise and Her Mother

A Southern Gothic Writer, a Very White Condiment

In her short lifetime, Flannery O’Connor wrote more than 600 letters to her mother. To read them, you must travel to the 10th floor of Emory University’s Woodruff Library, where they’re filed in a manuscript collection measuring almost 19 feet. If you make this journey, as I have, you will discover, among details of a more literary nature, the vigor of the author’s appetite.

In her first year as a graduate student at the University of Iowa, she wrote of sampling Triscuits at the local A&P and dining on ham—baked and boiled—at the school’s cafeteria. She reported eating a couple of eggs each day and declared her preference for Vienna sausages, vanilla pudding, and prunes costing a mere 27 cents. By spring of 1946, six months into her Iowa career, her purple dress no longer fit.

Of all the edibles that appear in the author’s correspondence with her mother, one inspires her most enthusiastic commentary: mayonnaise. She loves the thick, eggy spread, although she cannot spell its name. “Mayonaise” is as close as she gets. More often, she opts for “mernaise.” She considered the condiment a staple and lamented its scarcity in Iowa City at the time. The canned pineapple she chilled on her windowsill seemed lackluster without the familiar white dollop. Her tomatoes were all but naked. Where her sausages were concerned, mustard was a poor companion. She requested that her mother send her the homemade mayonnaise of her childhood, but instead, she received a store-bought jar, which arrived at her dorm on a Wednesday evening just in time for dinner.

My own fondness for mayonnaise matches O’Connor’s. She used it the way I do, which is the way my mother does and the way my grandmother did: as an all-purpose ingredient. Atop the dining tables of my youth, it served as both a spread and a garnish. It was a hero of family picnics, the critical binding agent for deviled eggs, pimento cheese, tomato pie, and potato salad. My mother, a Duke’s loyalist, creates recipes that call for the brand by the cupful; and when I stand at the kitchen counter, dip crackers into a jar and declare it lunch, I remind myself of her.

Perhaps this is why I did not immediately associate O’Connor’s love of mayonnaise with other banal particulars of her letters—travel itineraries and plumbing mishaps, ripped stockings and roommates with loud radios. I was not surprised to discover our shared affection. Though two generations apart, we both originated in the American South, a region with liberal ideas about the functions of mayonnaise. And I enjoyed learning that the master of grotesque Southern fiction dreamed of meals made perfect by the most polarizing of condiments. (In the US, the chasm between haters and devotees reaches beyond preference to ideology.) But despite my personal interest in the pages the author devoted to mayonnaise, I doubted their greater significance.

I believed, instead, that I was searching for juicier content. As a graduate student studying O’Connor’s work and life, my reason for reviewing her private papers was mostly scholarly. I wanted to better understand the intense matriarchy that shaped her early years and informed her fiction, and I hoped to uncover secrets that would reveal deep truths about the bond between mother and daughter.

There is much to be said of this close pair. Young Flannery began calling her mother Regina at age six, reportedly of her own volition. They shared an address for 34 of the author’s 39 years of life because of her struggle with lupus. While she was pursuing her literary career far from home—in Iowa City, New York and Connecticut—O’Connor exchanged letters with her mother almost every day. (This practice seems to have evolved as much from Flannery’s devotion as from Regina’s insistence on high-frequency communication.)

O’Connor’s fiction captures shades of her mother’s overbearing nature and preoccupation with propriety. Her published letters reinforce such impressions, painting the elder O’Connor as supportive yet comical in her rigidity and hopeless in her understanding of her daughter’s literary pursuits. So, in the sunlit reading room of Emory’s archives, I sought new insight into their rapport. I had read through nearly every letter in the collection before I found my way back to mayonnaise.

Ten times or more O’Connor writes about her appreciation of the sauce. In most of these musings she indicates that she learned its utility from her mother, just as I learned it from mine. As I examined this correspondence, I considered the breadth of local and familial interpretations for which mayonnaise allows. It is an ingredient that offers equal opportunities to delight and confound, depending, it seems, as much on your upbringing as your taste buds. The idea of pairing it with peanut butter may disgust the diner who spoons it into his omelets. Someone who blends it with crushed pineapple may recoil at its presence in a grilled-cheese sandwich. Like its appeal, its applications are personal and often regional.

I could read O’Connor’s requests for mayonnaise as evidence of homesickness, the kind of nostalgia favorite foods are intended to cure. And yet, the author never communicated any such longing. Rather, she wrote to her mother of thriving in Iowa and her intentions to develop her literary career outside of Georgia. (Had she not fallen ill at 25, she might have remained permanently beyond the borders of her home state.) Amid these declarations of her ambitions, O’Connor’s penned testimonials to mayonnaise are, to me, small attempts at connection. A thousand miles from her mother’s kitchen, the absence of the ingredient could become a shared curiosity and an acknowledgment of maternal influence. I imagine her wishing to affirm her love of home and family, even as she anticipated leaving both behind. The mayonnaise, she wrote to her mother, was a great help.

Caroline McCoy

Caroline McCoy is a writer and editor based in Boston. Her work appears in Blackbird, Electric Literature, The Washington Post, Paste, The Bitter Southerner and others.

2/13/2021

The Untold Story of the Highway Code

The Untold Story of the Highway Code

The British Highway Code – ‘…a guide to the proper use of the highway and a code of good manners…’ – celebrates the 90th anniversary of its first publication in 2021.

Here we look back at the evolution of the Code which tells the story of the development of road safety, driving and British roads over the decades.

The early years of driving

The first Highway Code cost one old penny and contained 21 pages of advice and information. It carried adverts for the RAC (founded 1897), AA (founded 1905), Castrol Motor Oil, BP Plus petrol, motor insurance and journals such as ‘Autocar’.

The late 19th century saw the first motorcars in Britain – a country whose roads had evolved for horse-drawn traffic.

In the early years of the 20th century anyone could drive a vehicle – the minimum driving age of 17 was not introduced until 1930.

When the Highway Code was first launched in 1931, there were 2.3 million motor vehicles on British roads, along with tens of thousands of horse-drawn vehicles.

To be on the road was glamorous. Drivers put their foot down. Pedestrians were often considered in the way; at fault if they became a casualty. In this dangerous heady world, around 7,000 people lost their lives in accidents every year. (By comparison, in 2019, there were over 40 million vehicles on British roads and 1,870 deaths).

Little had been done in terms of control or legislation. The Highway Code of 1931 was a first attempt to educate early motorists about driving carefully and responsibly.

Speed limits, driving tests and pedestrian crossings

Leslie Hore-Belisha’s 1934 Road Traffic Act introduced a 30mph speed limit in built-up areas (the speed limit of 20mph had been controversially removed by the 1930 Road Traffic Act after it was universally flouted and court cases built up). There were also stronger penalties for reckless driving and cyclists were required to have rear reflectors.

In addition, the Act instituted a compulsory driving test that came into force in 1935, but only for new drivers. Around one quarter of a million candidates applied.

The first driver to pass the half hour test of basic driving abilities and knowledge of the Highway Code was a Mr R. Beare of Kensington, 16 March 1935. Tests were suspended four years later for the duration of the Second World War (1939-1945), not resuming until 1946.

9,000 pedestrian crossings, with their distinctive flashing yellow globes (‘Belisha’ beacons), were erected in London in 1934, with the scheme extended to the provinces in the November. Initially crossings were marked with steel studs; zebra markings not appearing until 1949.

Other early road developments included white lines, which came into widespread use in the 1920s, prototype roundabouts and traffic lights dating from around the mid to late 1920s (the red/amber/green traffic light system began to be more widely adopted from 1933), and ‘catseyes’, patented in 1934, which came into their own during the blackouts of the Second World War and have been a common feature of roads ever since.

Early Road Signs

The second edition (1934) of the Highway Code also carried diagrams of road signs for the first time – just 10 in all – along with a warning about the dangers of driving when affected by alcohol or fatigue.

Stopping distances – broadly similar to today’s, despite huge advances in braking technology – made their first appearance in the third edition, published just post-war in 1946, along with new sections giving advice on driving and cycling.

The 1954 Highway Code carried brand new colour illustrations. There was an expanded traffic sign section which included an extended section on road signs, while the back cover gave instructions about first aid.

The first motorway

England’s first completed motorway, a revolutionary development in British roads – the 8 mile Preston bypass, later part of the M6 – was opened by the Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan in 1958.

The first 50 mile stretch of the M1 – from St Albans to Rugby – opened a year later in 1959, constructed by world-renowned contractors John Laing & Sons, who built much of post-Second World War Britain’s pioneering infrastructure, including housing, nuclear power stations, hospitals, factories and London’s Westway.

To reflect how motorways would radically affect motorists, the 1961 Highway Code was updated in its fifth edition with a section on motorway driving, including how to avoid drowsiness.

It also included a sombre, hand-written and signed introduction from Ernest Marples: ‘Casualties killed and injured (on the roads) are as high as for a major war’, ending with: ‘DO keep to the Code – and keep alive.’

There was no speed limit on motorways. Drivers were free to go as fast as they wanted. ‘Doing the ton’ (100mph) was a badge of honour, especially for motorcyclists. Marples was shocked by the speed of driving and introduced a national speed limit of 70mph in December 1965.

Built in 1964-1965, Forton evoked the glamour of early motorway driving – its Tower Restaurant offered waitress service and a vantage point with spectacular views. The restaurant closed in 1989.

Calvert and Kinneir’s motorway signs were modern, simple and easy to read when driving fast. The government became concerned that these signs made other British road signs – a chaotic mix of different words, styles and fonts – seem inadequate and outdated and asked them to redesign and rationalise the whole national road sign system.

The new signs came into force 1 January 1965 and the designs are still in use today on Britain’s roads and motorways.

The evolution of the highway code

The completely modernised 1968 version was the first to use photographs and 3D illustrations. It also introduced the ‘mirror – signal – manoeuvre’ routine when overtaking.

With mounting pedestrian casualties, the 1978 edition introduced the Green Cross Code to educate pedestrians about road safety (children were taught it in school, helped by superhero the ‘Green Cross Man’). The safety mantra was: ‘Think, Stop, Use Your Eyes and Ears, Wait Until It Is Safe to Cross, Look and Listen, Arrive Alive.’

This edition also launched new orange badges for people of disability, as well as having a section on vehicle security in response to rising car thefts.

As vehicles became more sophisticated, and roads busier and more complex, the Highway Code – most of whose rules are legal requirements – responded over the years with new instructions and advice in ever-growing sections.

Among them the use of seats belts, using mobile phones while driving, in-vehicle distractions such as Sat Nav, driving with illegal drugs in the system, remote control parking, smoking in vehicles, using mobility scooters, and the Theory Test – introduced in 1996 and replacing questions about the Highway Code that were originally posed during the driving test itself.

Today’s Highway Code is now 189 pages long and sells around 1 million copies annually. It is always listed in the annual best-seller list.

Header image: Motoring just outside Ludlow in Shropshire in the mid-1930s. The car is an Austin 7 (‘Baby Austin’) © Historic England BB70/09719.

Written by Nicky Hughes