11 Life Lessons From History’s Most Underrated Genius

Insights on work and creativity from the life of mathematician Claude Shannon, the most influential figure you’ve never heard of

By Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni, co-authors of A Mind at Play

For five years, we lived with one of the most brilliant people on the planet.

Sort of.

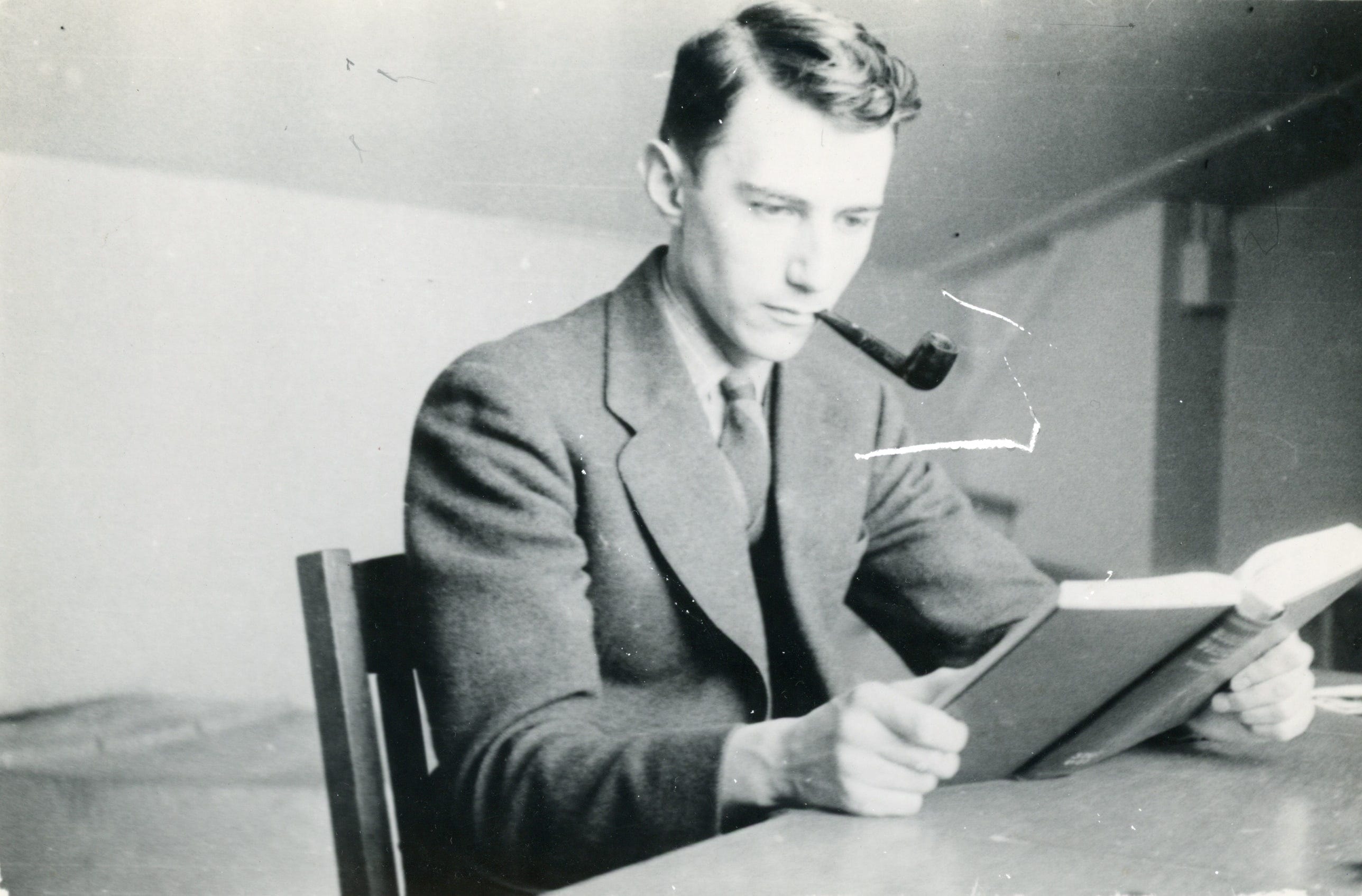

See, we spent those all-consuming five years writing our biography of American mathematician Claude Shannon, whose work in the 1930s and ’40s earned him the title of “father of the information age.” That’s how long it took us to understand the influence of the most important genius you’ve never heard of, a man whose intellect was on par with that of Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton.

During that time, we spent more time with the deceased Claude Shannon than we have with many of our living friends. He became something like the roommate in the spare bedroom of our minds, the guy who was always hanging around and occupying our headspace.

Geniuses have a unique way of engaging with the world, and if you spend enough time examining their habits, you discover the behaviors behind their brilliance. Whether or not we intended it to, understanding Claude Shannon’s life gave us lessons on how to better live our own.

That’s what follows in this essay. It’s the good stuff our roommate left behind.

Claude who?

His name may not ring a bell. Don’t worry—we initially didn’t know much about him, either.

So, who was Claude Shannon?

Within engineering and mathematics circles, Shannon is a revered figure. At 21, he published what’s been called the most important master’s thesis of all time, explaining how binary switches could do logic and laying the foundation for all future digital computers. At the age of 32, he published A Mathematical Theory of Communication, which Scientific American called “the Magna Carta of the information age.” Shannon’s masterwork invented the bit, or the objective measurement of information, and explained how digital codes could allow us to compress and send any message with perfect accuracy.

But Shannon wasn’t just a brilliant theoretical mind — he was a remarkably fun, practical, and inventive one as well. There are plenty of mathematicians and engineers who write great papers. There are fewer who, like Shannon, are also jugglers, unicyclists, gadgeteers, first-rate chess players, codebreakers, expert stock pickers, and amateur poets.

Shannon worked on the top-secret transatlantic phone line connecting FDR and Winston Churchill during World War II and co-built what was arguably the world’s first wearable computer. He learned to fly airplanes and played the jazz clarinet. He rigged up a false wall in his house that could rotate with the press of a button, and he once built a gadget whose only purpose when it was turned on was to open up, release a mechanical hand, and turn itself off. Oh, and he once had a photo spread in Vogue.

Think of him as a cross between Albert Einstein and the Dos Equis guy.

Asking the questions he probably wouldn’t

We aren’t mathematicians or engineers; we write books and speeches, not code. That meant we had a steep learning curve in making sense of Shannon’s work.

Because we approached this book as learners, we were particularly interested in a broader, more generalist set of questions: How does a mind like Shannon’s work? What shapes a mind like that? What does a mind like that do for fun? What can we take from it to be just a bit more brilliant in our own pursuits, whatever they happen to be?

Shannon was never especially interested in offering direct answers to questions like those. If he were alive to read this piece, he’d probably laugh at us. What got him up in the morning was dissecting how things worked, not digressions into creativity and productivity. Still, he has plenty to teach us in those areas. To that end, we’ve distilled what we’ve learned from Shannon over these past few years into this piece. It isn’t a comprehensive list by any means, but it does begin, we hope, to reveal what this unknown genius can teach the rest of us about thinking — and living.

Cull your inputs, inbox zero be damned

We know that staying focused is considerably more difficult now, with the constant distractions of smartphones and social media, than it was in Shannon’s mid-20th-century America (and yes, we suppose he bears some inadvertent blame for this). But distractions are a permanent feature of life in any era, and Shannon shows us that shutting them out isn’t just a matter of achieving random bursts of concentration. It’s about consciously designing one’s life and work habits to minimize them.

For one, Shannon didn’t allow himself to get caught up in clearing out his inbox. Letters he didn’t want to respond to went into a bin labeled “Letters I’ve Procrastinated On for Too Long.” In fact, we pored over Shannon’s correspondence at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., which keeps his papers on file, and we found far more incoming letters than outgoing ones. All that time saved was more time to plow into research and tinkering.

Shannon extended the same attitude to his time in the office, where his colleagues regularly expected to find his door closed (a rarity in Bell Labs’ generally open-door culture). None of Shannon’s colleagues, to our knowledge, remembered him as rude or unfriendly, but they do remember him as someone who valued his privacy and quiet time for thinking.

On the other hand, colleagues who came to Shannon with bold new ideas or fascinating engineering puzzles remembered hours of productive conversations. That’s just to say that Shannon was deliberate about how he invested his time: in stimulating ideas, not in small talk. Even for those of us who are more extraverted than he was—and, to be honest, that’s nearly all of us—there’s something to learn from how intentionally and consistently Shannon turned his work hours into a distraction-free zone.

Big picture first, details later

In his mathematical work, Shannon had a quality of leaping right to the central insight and leaving the details to be filled in later. As he once explained it, “I think I’m more visual than symbolic. I try to get a feeling of what’s going on. Equations come later.” It was as if he saw solutions before he could explain why they were correct.

As his graduate student Bob Gallager, who went on to become a leading information theorist himself, recalled, “He would say, ‘Something like this should be true’… and he was usually right… You can’t develop an entire field out of whole cloth if you don’t have superb intuition.”

Occasionally, this got Shannon into trouble: Academic mathematicians sometimes accused him of being insufficiently rigorous in his work. Usually, though, their critiques were misguided. “In reality,” said mathematician Solomon Golomb, “Shannon had almost unfailing instinct for what was actually true.” If the details of the journey needed filling in, the destination was almost always correct.

Most of us, of course, aren’t geniuses, and most of us don’t have Shannon-level intuition. So, is there anything to learn from him here? We think there is: Even if our intuitions don’t lead us to anything groundbreaking, they often have a wisdom that we can choose to tune in to.

Worrying about missing details and intermediate steps is a sure way to shut down our intuitions and miss out on some of our best shots at creative breakthroughs. Expecting our big ideas to unfold logically from premise to conclusion is a misunderstanding of the way creativity usually works in practice. Waiting for a neat and tidy epiphany usually means waiting for a train that’s never arriving.

Don’t just find a mentor—allow yourself to be mentored

A lot of writing about mentorship tends to treat a mentor as something you acquire: Find the right smart, successful person to back your career and you’re all set.

It’s not that simple. Making the most of mentorship doesn’t just require the confidence to approach someone whose guidance can make a difference in your development. It requires the humility to take that guidance to heart, even when it’s uncomfortable, challenging, or counterintuitive. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Shannon’s most pivotal mentor was probably his graduate school adviser at MIT, Vannevar Bush, who went on to coordinate the American scientific effort in World War II and became the first presidential science adviser. Bush recognized Shannon’s genius, but he also did what mentors are supposed to do: He pushed Shannon out of his comfort zone in some productive ways.

For instance, after the success of Shannon’s master’s thesis, Bush urged him to write his PhD dissertation on theoretical genetics, a subject Shannon had to pick up from scratch and that was far afield from the engineering and mathematics he had spent years working on. That Bush pushed Shannon to do so testifies to his trust in his protégé’s ability to rise to the challenge; that Shannon agreed testifies to his willingness to stretch himself. Bush knew what he was doing, and Shannon was humble enough to trust his judgment and let himself be mentored.

Accepting real mentorship is, in part, an act of humility: The best of it comes when you’re actually willing to trust that your mentor sees something you don’t. There’s a reason, after all, that you sought them out in the first place. Be humble enough to listen.

You don’t have to ship everything you make

Bush left his imprint on Shannon in another way: He defended the value of generalizing over specializing. As he told a group of MIT professors:

In these days, when there is a tendency to specialize so closely, it is well for us to be reminded that the possibilities of being at once broad and deep did not pass with Leonardo da Vinci or even Benjamin Franklin. Men of our profession — we teachers — are bound to be impressed with the tendency of youths of strikingly capable minds to become interested in one small corner of science and uninterested in the rest of the world… It is unfortunate when a brilliant and creative mind insists upon living in a modern monastic cell.

Bush encouraged Shannon to avoid cells of all kinds — and Shannon’s subsequent career proves how deeply he absorbed the lesson.

We know: Bush’s advice would probably sound unfashionable these days. So many of the pressures in our professional lives push us to specialize at all costs, to cultivate that one niche skill that sets us apart from the competition, and to keep hammering away at it. In this view, people whose interests are broad rather than deep are basically unserious. What’s worse, they’re doomed to be overtaken by rivals who know how to really focus.

It’s a view that would have exasperated Shannon. Bush’s generalist gospel struck such a deep chord with him, we think, because it accorded with Shannon’s natural curiosity. He was so successful in his chosen fields not just because of his raw intellectual horsepower, but because of how deliberately he kept his interests diverse. His remarkable master’s thesis combined his interests in Boolean logic and computer-building, two subjects that were considered entirely unrelated until they fused in Shannon’s brain. His information theory paper drew on his fascination with codebreaking, language, and literature. As Shannon once explained to Bush, “I’ve been working on three different ideas simultaneously, and strangely enough it seems a more productive method than sticking to one problem.”

While he was diving into these intellectual pursuits, Shannon kept his mind agile by taking up an array of hobbies: jazz music, unicycling, juggling, chess, gadgeteering, amateur poetry. He was a person who could have used his talents to burrow ever deeper and deeper into a chosen field, wringing out variations on the same theme for his entire career. But we’re fortunate that he chose to be a dabbler instead.

Chaos is okay

When he partnered with Shannon in 1961 to build a pioneering wearable computer to beat the house at roulette, mathematician Ed Thorp got to see Shannon’s work environment up close — in particular, the huge home workshop where Shannon did the bulk of his tinkering.

Thorp later described the workshop as “a gadgeteer’s paradise… There were hundreds of mechanical and electrical categories, such as motors, transistors, switches, pulleys, gears, condensers, transformers, and on and on.” Shannon had no qualms about getting his hands dirty, leaving machine parts and half-finished projects scattered all over the place, and jumping from project to project as he followed his curiosity.

Shannon’s more academic pursuits also resembled that workshop. His attic was stuffed with notes, half-finished articles, and “good questions” on ruled paper.

On one hand, we can regret the amount of unfinished work Shannon never got around to sending out into the world. On the other hand, we can recognize that chaos was the condition of the remarkable work he did do: Rather than pouring mental energy into tidying up his papers and workspace, Shannon poured it into investigating chess, robotics, or investment strategies. Call him an early adopter of The Joy of Leaving Your Shit All Over the Place.

Time is the soil in which great ideas grow

Shannon’s breadth of interests meant that his insights sometimes took time to come to fruition. Often, unfortunately, he never got around to publishing his findings at all. But if Shannon’s tendency to follow his curiosity sometimes rendered him less productive, he also had the patience to keep coming back to his best ideas over the course of years.

For instance, his 1948 information theory paper was nearly a decade in the making: He was just finishing grad school in 1939 when he first conceived the idea of studying “some of the fundamental properties of general systems for the transmission of intelligence, including telephony, radio, television, telegraphy, etc.” The years between the first inkling of the idea and its publication would take Shannon not only deeper into the study of information but also into work aiding America’s World War II effort, including research on anti-aircraft gunnery and cryptography. All along, Shannon’s information theory continued to germinate, even when he had to work on it in his free time.

This is probably the hardest lesson for us to swallow, living in the age that we do. We bathe in instant gratification. But for people in the creative, entrepreneurial, and idea-making worlds, there may be no more useful advice we need to hear: Genius takes time.

Remember also: Shannon wasn’t working on information theory full-time for 10 years. It was, for many of those years, his side hustle. Maybe the ultimate side hustle. But his endurance in sticking with it yielded the most important work he’d ever produce.

What could we do in our spare time if we stuck with something for long enough?

Consider the content of your friendships

Shannon was never one to get caught up in jockeying for status, play office politics, or try to win over every critic. The pleasure of problem-solving was worth more to him than all of that, and so when it came to choosing his relatively small number of friends, Shannon deliberately chose those who took pleasure in the same thing and who helped bring out the best in him.

During World War II, those friends included Alan Turing, with whom Shannon struck up a lively intellectual exchange during Turing’s fact-finding trip to study American cryptography on behalf of the British government. At Bell Labs, Shannon also bonded with fellow engineers Barney Oliver and John Pierce, each of whom was a pioneering figure in the history of information technology in his own right.

Shannon grew smarter and more creative because he chose to surround himself, almost exclusively, with people whose smarts and creativity he admired. More than most of us, he was deliberate in his friendships, choosing only the friends who drew out his best.

What does that mean for the rest of us nongeniuses? It means asking yourself not just who your friends are but also what you do together. Think more deliberately about the substance of your time with them, and if you find it lacking, change it.

Put money in its place

There’s a great line from stoic philosopher Seneca: “He is a great man who uses earthenware dishes as if they were silver; but he is equally great who uses silver as if it were earthenware. It is the sign of an unstable mind not to be able to endure riches.” Seneca’s point: The pursuit of money is a powerful distraction from the pursuit of what truly matters. Money is neither the root of all evil nor the solution to all of our problems. The question is whether it gets in the way of what’s morally important.

Shannon, who was a successful investor in early Silicon Valley companies and pursued stock-picking as one of his many hobbies, is an excellent example of what it looks like to be wealthy without being consumed by the pursuit of wealth. He saw his financial success as an opportunity, not to live lavishly, but to spend more time on the gadgeteering projects he loved. His investment returns funded, for instance, his research into the physics of juggling, as well as his invention with Thorp of their roulette-beating wearable computer.

None of us need to be told that the pursuit of money can obscure what’s important and valuable. But it is useful to remind ourselves that wealth nearly always comes as an indirect effect of incredible work rather than as the end goal. Silicon Valley entrepreneur Paul Graham has put it like this: “I get a lot of criticism for telling founders to focus first on making something great, instead of worrying about how to make money. And yet, that is exactly what Google did. And Apple, for that matter. You’d think examples like that would be enough to convince people.”

Fancy is easy. Simple is hard.

Shannon wasn’t impressed by his colleagues who wrote the most detailed tomes or whose theories were the most complex. What impressed him the most — in a way that reminds us of Steve Jobs — was radical simplicity.

In a 1952 talk to his fellow Bell Labs engineers, Shannon offered a crash course in the problem-solving strategies that had proven most productive for him. At the top of the list: You should first approach your problem by simplifying.

“Almost every problem that you come across is befuddled with all kinds of extraneous data of one sort or another,” Shannon said, “and if you can bring this problem down into the main issues, you can see more clearly what you’re trying to do.”

Gallager, Shannon’s graduate student, saw this process of radical simplification in action when he came to Shannon’s office one day with a new research idea. As Gallagher recalled:

He looked at it, sort of puzzled, and said, “Well, do you really need this assumption?” And I said, “Well, I suppose we could look at the problem without that assumption.” And we went on for a while. And then he said, again, “Do you need this other assumption?”… And he kept doing this, about five or six times… At a certain point, I was getting upset, because I saw this neat research problem of mine had become almost trivial. But at a certain point, with all these pieces stripped out, we both saw how to solve it. And then we gradually put all these little assumptions back in, and then, suddenly, we saw the solution to the whole problem. And that was just the way he worked.

A lot of us are trained to think that our ability to grapple with ever-more-complex concepts is the measure of our intelligence. The more complicated the problem, the smarter the person needed to solve it, right? Maybe. Shannon helps us see how the opposite might also be true. Achieving simplicity may actually be the more intellectually demanding endeavor.

Never confuse simplicity with simplemindedness. It takes work to distill, to get at the essence of things. If you stop yourself from saying something in a meeting because you’ve just thought, “Well, that’s just too simple,” you might want to think again. It may be that it’s the very thing that needs to be said.

Value freedom over status

Reflecting on the arc of his career, Shannon confessed, “I don’t think I was ever motivated by the notion of winning prizes, although I have a couple of dozen of them in the other room. I was more motivated by curiosity. Never by the desire for financial gain. I just wondered how things were put together. Or what laws or rules govern a situation, or if there are theorems about what one can’t or can do. Mainly because I wanted to know myself.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. Shannon was regularly given awards that he wouldn’t go to the trouble of accepting. Envelopes inviting him to give prestigious lectures would arrive; he’d toss them into the “Procrastination” bin we mentioned earlier. He accumulated so many honorary degrees that he hung the doctoral hoods from a device that resembled a rotating tie rack (which he built with his own hands). Whether the awarding institutions would have found that treatment fitting or insulting, it speaks to the lightness with which Shannon took the work of being lauded.

There were, of course, certain strategic and personal advantages to being immune to the pull of trophies and plaques. For Shannon, it gave him the ability to explore areas of research that no other “respectable” scientist might have ventured into: toy robots, chess, juggling, unicycles. He built machines that juggled balls and a trumpet that could breathe fire when it was played. Time and again, he pursued projects that might have caused others embarrassment, engaged questions that seemed trivial or minor, and then managed to wring breakthroughs out of them.

Would Shannon have been able to do all of that while chasing a Nobel? Possibly. But the fact that he didn’t give much thought to those external achievements allowed him to devote far more thought to the work itself.

We admit: It’s easier to write those words than to live by them. We’re all conscious of our status, and for the ambitious and talented, it’s especially tough to be indifferent to it. Shannon can help us break that hold, though, because his example points us to the rich prize on the other side of indifference: freedom. Even when it risked his status, Shannon pointedly did not stay in his lane. He gave himself the freedom to explore whichever discipline caught his fancy, and that freedom came, in part, from not caring what other people thought of him.

When we’re in the midst of chasing awards and honors, we often forget the way they can crowd out freedom. Nothing weighs you down like too many pieces of flair.

Don’t look for inspiration—look for irritation

How many of us, in search of a breakthrough, sit around waiting for inspiration to strike? That’s the wrong way to go about it.

One of the people who explained this the most trenchantly was painter Chuck Close. As he put it, “Inspiration is for amateurs — the rest of us just show up and get to work… If you hang in there, you will get somewhere.”

Shannon believed something quite similar when it came to looking for a great “science idea.” The idea might come from a good conversation, tinkering in the workshop, or the kind of aimless play he indulged in for much of his life — but above all, it came from doing, not waiting.

As Shannon told his fellow Bell Labs engineers, the defining mark of a great scientific mind is not some ethereal capacity for inspiration, but rather a quality of “motivation… some kind of desire to find out the answer, the desire to find out what makes things tick.” That fundamental drive was indispensable: “If you don’t have that, you may have all the training and intelligence in the world, [but] you don’t have the questions and you won’t just find the answers.”

Where does that fundamental drive come from? Shannon’s most evocative formulation of that elusive quality put it like this: It was “a slight irritation when things don’t look quite right,” or a “constructive dissatisfaction.” In the end, Shannon’s account of genius was a refreshingly unsentimental one: A genius is simply someone who is usefully irritated. And that useful irritation doesn’t come until, somewhere in the midst of the work, you stumble onto something that troubles you, pulls at you, doesn’t look quite right.

Don’t run away from those moments. Hold onto them at all costs.

A final thought: The internet, the digital age, the technologies that underlie it all — these are remarkable human achievements. But we can too easily forget what their origins are, where they sit in the flow of our history, and what kinds of people brought them about. We think there is something important in beginning to learn these things.

Learning isn’t just about understanding the substance of what’s been built—it’s also about understanding the spirit in which it was built. So many of the great sparks of innovation that made our world possible grew from the spirit of curiosity and creativity. They came from minds that, like Claude Shannon’s, saw their work as a game.

We think that’s a spirit worth remembering. More than that, we think it’s one worth living by.

The inspiration for this post comes from a marvelous essay by author and entrepreneur Ben Casnocha. In 2015, he wrote a piece summarizing the lessons he took from spending several years at the elbow of LinkedIn founder and Greylock partner Reid Hoffman. It’s a fantastic read.

We’d love to hear from readers. Rob can be contacted at goodman1@gmail.com and Jimmy at jimmysoniwriting@gmail.com. We promise not to put you in the “Procrastination” folder. You can also subscribe to our articles here.

Written by

Co-Author, A MIND AT PLAY: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age (http://amzn.to/2pasLMz)

- Claude who?

- Asking the questions he probably wouldn’t

- Cull your inputs, inbox zero be damned

- Big picture first, details later

- Don’t just find a mentor—allow yourself to be mentored

- You don’t have to ship everything you make

- Chaos is okay

- Time is the soil in which great ideas grow

- Consider the content of your friendships

- Put money in its place

- Fancy is easy. Simple is hard.

- Value freedom over status

- Don’t look for inspiration—look for irritation