Playing the Post Card

of Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49

The difference between a collector of post cards and another [...] is

that he can communicate with other collectors with the help of post

cards, which enriches and singularly complicates the exchange. In the

bookstore I felt that between them [collectors of post cards] they

formed, from State to State, from nation to nation, a very powerful

secret society in the open air. -- The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond, Jacques Derrida.

For many readers, the primary attraction of Thomas Pynchon's second novel, The Crying of Lot 49

(published in 1966) is the fact that it is short, a mere "novella,"

only 138 pages long in the paperback edition. By contrast, Pynchon's

first and third novels, V. (1963) and Gravity's Rainbow (1973), are quite long, especially the latter, which is over 700 pages. Furthermore, the plot of The Crying of Lot 49

is relatively simple and straightforward, while those of the other two

are not. And so, Pynchon's novella appears to obey what Herbert Spencer

calls an "economy of creative effort." In The Philosophy of Style, Spencer states: "To so present ideas that they may be apprehended with the least possible mental effort, is the desideratum."

For Pynchon, who is, like William Burroughs,

commonly regarded as -- indeed, praised for being -- a writer of

"difficult" fiction, there must have been risks involved in writing an

"economical" book, one without "waste" of any kind. In The Post Card,

Jacques Derrida sketches out the incredible, perhaps even infinite

complexity of the subject to which Pynchon's novella addresses itself

(i.e., the workings of postal systems): "[I] want to write and first to

assemble an enormous library on the courrier [both letter and

delivery person], the postal institutions, the techniques and mores of

telelcommunication, the networks and epochs of telecommunication

throughout history -- but the 'library' and the 'history' themselves are

precisely but 'posts,' sites of passage or of relay among others,

stases, moments or effects of restance [standing or remaining]

and also particular representations, narrower and narrower, shorter and

shorter sequences, proportionally, of the Great Telematic Network, the worldwide connection."

Even if one were able to compress such a huge subject into the pages of a short book (The Post Card

is over 500 pages), one might legitimately wonder if something as

familiar, ordinary and even banal as the post office is fit for

"serious" literature. "We have played the post card against literature,"

Derrida explains; post cards are "inadmissible literature." No doubt

Pynchon didn't want his readers to apply a remark about a play (The Courier's Tragedy) that is contained within or enveloped by The Crying of Lot 49

to the novella itself: "It was written [merely] to entertain people.

Like horror movies. It isn't literature, it doesn't mean anything." And

so Pynchon wrote The Crying of Lot 49 as one would write a post

card, something that is short, easy to read, and yet, despite its

apparent superficiality and "innocence," the carrier of meanings that

are indecipherable to all except those to whom it is addressed.

* * * *

If indeed the novella is a kind of post card, then the picture

-- usually placed on the side opposite the address/message/stamp side

-- is easy to locate. Amid much fanfare, it is unveiled at the end of

the first chapter: "the central painting of a triptych, titled 'Bordando

el Manto Terrestre' . . . by the beautiful Spanish exile Remedios

Varo." According to Pynchon's narrator, this painting depicts the

following scene.

[A] number of frail girls with heart-shaped faces, huge eyes, spun-gold

hair, prisoners in the top room of a circular tower, embroidering a kind

of tapestry which spilled out the slit windows and into a void, seeking

hopelessly to fill the void: for all the other buildings and creatures,

all the waves, ships and forests of the earth were contained in this

tapestry, and the tapestry was the world.

For Oedipa Maas, the novella's protagonist, this painting is deeply

moving and highly relevant to her own situation. She happened to see it

in Mexico City, where her then-lover, a rich man named Pierce

Inverarity, had once taken her on a tryst.

Oedpia, perverse, had stood in front of the painting and cried. No one

had noticed; she wore dark green bubble shades. For a moment she

wondered if the seal around her sockets were tight enough to allow the

tears simply to go on and fill up the entire lens space and never dry.

She could carry the sadness of the moment with her that way forever, see

the world refracted through those tears, those specific tears, as if

indices as yet unfound varied in important ways from cry to cry.

She had looked down at her feet and known, then, because of a painting,

that what she stood on had only been woven together a couple thousand

miles away in her tower, was only by accident known as Mexico, and so

Pierce had taken her away from nothing, there'd been no escape.

(Emphasis added.)

According to Janet A. Kaplan, author of Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys, Pynchon saw Bordando el Manto Terrestre

("Embroidering Earth's Mantle") when, as part of the first full

retrospective of the painter's work, it was displayed at the Palacio de

Bellas Artes in Mexico City in 1964, a year after her death at the age

of 55. Painted in 1961, el Manto (oil on masonite, roughly 40 by

48 inches) is the central panel in an autobiographical triptych. It is

possible that Pynchon, writing Lot 49 in 1965, recalled the painting from memory or incomplete notes, and not with a reproduction of it set in front of him. He gets a lot wrong.

1. Nothing here suggests that the golden-haired girls inside the octagonal (not circular) tower are Rapunzel-like prisoners. (By way of setting the stage for his recollection of Bordando el Manto Terrestre,

Pynchon's narrator says that, prior to her affair with Pierce, Oedipa

had "conned herself into the curious, Rapunzel-like role of pensive girl

somehow, magically, prisoner among the pines and salt fogs.") In Varo's

painting, there are six girls in total, all the same height and build,

all dressed the same way, like identical sisters, a sextuplet. We can

only see the faces of two of them. Though both girls have their eyes

lowered and focused down upon their busy hands, they are clearly smiling. They look so relaxed that they might be asleep and smiling at their dreams.

They might also be smiling because they are plotting their escape. If

viewers look closely enough, they can see -- upside-down and hidden

within one of the folds in the tapestry -- that one of the girls has, in

Varo's own words, "embroidered a trick [right into the tapestry] in

which one can see her together with her lover." This detail leads Janet

A. Kaplan to conclude that, "unlike Rapunzel [...], Varo's young heroine

imprisoned in the tower is not merely a metaphor for confinement, but

also an agent of her own liberation. To free herself [...] she connives

to flee the tower that isolates her from the very life she is expected

to create." (The third part of the triptych, The Escape, shows the girl and her lover fleeing/flying into the mountains.)

2. "Slit windows" is a misleading description, because the openings

in the tower are positioned too low for anyone in the room (either

standing or sitting down) to see out of them. (Kaplan calls them

"battlements.") Strictly speaking, there are no "real" windows in the

tower; no one inside can see out, into the "outdoors"; the tower is in

some sense blind. The only window is the one (imaginary, metaphorical

and/or hypothetical) opened up by the painter, who accomplishes the

trick by "removing" or rendering transparent one of the walls. In a nice

touch, the shape of this dream-like window exactly matches that of the

alcove, which is in the back part of the room, facing us. This echoing

or doubling effect suggests just how far into the "recesses" we (and no

one else) are seeing.

3. The tapestry that comes rolling out of the tower doesn't seek to "fill" any void, nor does it manage to "contain" the whole world. (In addition to "embroidering" or "weaving," Bordando

can also mean "bordering" or "circumnavigating.") There are several

pockets left open, uncovered by fabric, and in each case these pockets

are not empty or "void," but are filled with water, are in fact "bodies"

of water, several of them traveled by boats. And so the tapestry seeks

only to form or fill dry land, the land masses of the world, not the

oceans and lakes, not the entire planet. As in the Bible, (the) land is

only a "mantle" (a piece of clothing or the crust worn by the Earth),

not the original, naked, oceanic Creation itself. Ironically, in his

novel V., Pynchon himself had warned against making a very similar mistake.

Perhaps history this century [...] is rippled with gathers in its fabric

such that if we are situated [...] at the bottom of a fold, it's

impossible to determine warp, woof or pattern anywhere else. By virtue,

however, of existing in one gather it is assumed there are others,

compartmented off in sinuous cycles each of which come to assume greater

importance than the weave itself and destroy any continuity [...] We

are accordingly lost to any sense of a continuous tradition. Perhaps if

we lived on a crest, things would be different. We could at least see.

In seeing or remembering only the tapestry, and not the bodies of water, Pynchon has, as it were, blindly mistaken

the view from "the bottom of a fold" for the view "on a crest." He

doesn't see or has perhaps forgotten the following paradox: bodies of

water make up the pre-existing and "continuous tradition," not the

added-on-later tapestry of the land, which is only a "compartmented"

fold within the (larger) weave.

4. Unaccountably, Pynchon's narrator makes no reference whatsoever to

the two other women in the tower. (Six plus two is eight. There's a

certain symmetry: eight women, eight walls.) One of these women is easy

to miss: she is sitting back in the alcove, where she appears to be

playing a musical instrument, perhaps a recorder. But the other woman

requires a real effort to overlook: she is purple, very tall and

slender, and standing near the epicenter of the room.

(No doubt Oedipa's LSD-crazed, devoutly Freudian psychoanalyst Dr

Hilarius would say that Pynchon has averted his eyes from what she

represents, i.e., mommy's missing phallus.)

A magician or sorceress of some kind, the tall woman holds a small

book in her left hand and, with her right hand, uses a long rod to stir a

turquoise potion. The cauldron is utterly remarkable. Double-bowled,

with one bowl atop the other, connected together by a narrow tube,

around which a magic ring circles -- the cauldron sits at the exact

center of the room. It is the source of two of the three sets of threads

out of which the girls (using both hands) are weaving and embroidering

the tapestry. (The third set of threads is quite obscure: it comes out

of holes in the floor, and it isn't clear how the girls are

incorporating it into the tapestry.) Perhaps the small book contains the

spells, songs or instructions necessary to script the mantle,

and the magician is needed to translate them, sing them or read them

aloud. (Janet A. Kaplan likens the scene Varo has depicted to "a

medieval scriptorium," a monastery for the writing or copying of

manuscripts.)

In a set of curious touches, the magician's face is veiled (and so we

can't see if her mouth is open or closed); and her eyes are averted,

off to her right (and so she doesn't see us, peering "in" at her.) (Her

averted gaze is all the more striking when compared to one of the girls

in the first panel in the triptych, Toward the Tower, who, in

Kaplan's words, "rebels, her gaze reaching out [back to/at the viewers]

defiantly, resisting what Varo termed 'the hypnosis.'"). As viewers, we

see everything; in Embroidering the Earth's Mantle, the viewers are invisible,

unseen by those who are seen. In the case of the magician, we might

have caught her during a pause, interruption or delay in the ceremony,

perhaps a moment of distraction or day-dreaming.

None of this is adequately captured, indeed, most of it changed to the opposite

of what it had previously been, by Pynchon's recollection: "Such a

captive maiden [Oedipa], having plenty of time to think, soon realizes

that her tower, its height and architecture, are like her ego only

incidental: that what really keeps her where she is is magic, anonymous

and malignant, visited on her from outside and for no reason at all."

The lesson for truly attentive readers of The Crying of Lot 49

is easy to see. As we follow Oedipa "from cry to cry" -- from

self-pitying tears to tears of mourning (shed for Pierce Inverarity

after his death), from "crying" (shedding tears) to the "crying"

(auctioning off) of Lot 49 -- we must pay careful attention to the

"economy" or "play" of Pynchon's writing, to his delays as well as to

his deliveries, to what he leaves out, changes or gets wrong. It is

possible that, embroidered into his elaborate yarns, there are designs

of which he himself is not fully aware.

* * * *

By the time Pynchon recalls and displays Bordando el Manto Terrestre for his readers, two things of consequence have already happened:

1). Oedipa has already cried once ("Mucho [her husband], baby," she

cried, in an access [sic] of helplessness"). Over the course of the

novella, Oedipa will cry a total of five times, and two other people --

Dr Hilarius, and Emory Bortz, an author and college professor -- will

cry (out) once each, making a grand total of seven cries. Perhaps this number, the square root of 49 -- itself an echo of the number of days of mourning in the Tibetan Book of the Dead -- is meant to evoke the seven-day-long period of mourning in Judaism called shiva or perhaps the "seven years' bad luck" Oedipa fears she's going to have after she breaks a mirror in her hotel room.

2). the plot has already begun. Hopefully without giving too

much of the game away in advance, it must be said that, here, "the plot"

means "the dramatic action," but also "the burial place" and "the

conspiracy."

This is the novella's very first sentence:

One summer afternoon, Mrs Oedipa Maas came home from a Tupperware party

whose hostess had put perhaps too much kirsch in the fondue to find that

she, Oedipa, had been named executor, or she supposed executrix, of the

estate of one Pierce Inverarity, a California real estate mogul who had

once lost two million dollars in his spare time but still had assets

numerous and tangled enough to make the job of sorting it out more than

honorary.

The narrator's "postal" metaphor ("the job of sorting it out")

foreshadows the fact that Oedipa learns the news of her new duties (ner

"naming") by letter. Sent "from the law firm of Warpe, Wistfull,

Kubitschek and McMingus, of Los Angeles, and signed by somebody named

Metzger," it explains that a codicil to the dead man's will mandates

that, post obit, "Metzger was to act as co-executor and special

counsel in the event of any involved litigation." Together, Oedipa and

Metzger are required, in the words of the narrator, to "learn intimately

the books and the business, go through probate, collect all debts,

inventory the assets, get an appraisal of the estate, decide what to

liquidate and what to hold on to, pay off claims, square away taxes,

distribute legacies. . . ."

Pierce had only been briefly involved with Oedipa, had not seen

her in a very long time, and had attached the codicil a year before his

death. Furthermore, the will itself had "only just now" been found. And

so, troubling questions arise. What accounts for all the delays? Why

wasn't all of this settled ages ago? Why had Pierce named Oedipa

(of all people) to be a co-executor? Didn't Pierce have any siblings,

ex-wives or children? Surely one of his legatees would serve better as

the distributor of his legacies. Oedipa has no experience in such

matters. "If only so much didn't stand in her way," the narrator says:

"her deep ignorance of law, of investment, of real estate, ultimately of

the dead man himself."

To get an answer to this Sphinx-like riddle ("why me?"), Oedipa must

"pierce" the "inveracity" of the death-shroud of Pierce Inverarity, and

thereby learn the naked truth about or standing behind her ex-lover.

Oedipa must dig the dead man, decrypt his meaning. At stake in this

quest for the truth isn't just Oedipa's peace of mind or her bond (her

"word" to the probate court), but also the value of speculating upon a

contemporary, feminized version of Oedipus; the interest of the novella

itself; the way Pynchon is "evaluated" and "appraised" by critics,

professors and other readers, book sales, etc etc.

But what happens if Pierce (declared to be of sound mind and body) didn't

in fact know exactly what he was doing when he named Oedipa

co-executor? A few pages from the novella's end, the narrator asks,

"Might Oedipa Maas yet be his heiress; had that been in the will, in

code, perhaps without Pierce really knowing, having been by then too

seized by some headlong expansion of himself, some visit, some lucid

instruction?" There is no answer, only the following consolation:

"Though she could never again call back any image of the dead man to dress up,

pose, talk to and make answer, neither would she lose a new compassion

for the cul-de-sac he'd tried to find a way out of, for the enigma his

efforts had created" (emphasis added). But finding compassion for blind

stumbling isn't the same thing as seeing the naked truth.

"As things developed," the narrator says, back at the beginning, "she

[Oedipa] was to have all manner of revelations." Some will have

concerned Pierce, some Oedipa herself, still others her husband Wendell

("Mucho") Maas. But the balance of these revelations will have concerned

what the narrator cryptically refers to as "what remained yet had

somehow, before this, stayed away": the possibly apocryphal, semi-secret

existence of an 800-year-old underground postal system that is

sometimes called "the Tristero," other times "WASTE." According to the

narrator,

Much of the [central] revelation was to come through the stamp

collection Pierce had left, his substitute often for her -- thousands of

little colored windows into deep vistas of space and time [...], he

could spend hours peering into each one, ignoring her. She had never

seen the fascination. The thought now that it would all have to be

inventoried and appraised was only another headache. No suspicion at all

that it might have something to tell her. Yet if she hadn't been set up

or sensitized, first by her peculiar seduction [by Metzger], then by

other, almost offhand things, what after all could the mute stamps have

told her, remaining then as they would've only ex-rivals, cheated as she

by death, about to be broken up into lots, [ready to be sent] on route to any number of new masters? (Emphasis added.)

Despite his knowledge that this story is to be short (a "mere" post card), not long (a "proper" letter), the narrator doesn't get to the stamp collection right away. There's a couple of places that must be visited first, before

it can be called upon. "It got seriously under way, this sensitizing,

either with the letter from Mucho or the evening she and Metzger drifted

into a strange bar known as The Scope. Looking back she forgot which

had come first." But the "omniscient" narrator hasn't forgotten the

ordering. (He can be trusted: his business is giving order or "taxis" to the plot.) The letter or, rather, the envelop in which it was mailed, came first.

It may have been an intuition that the letter would be newsless inside

that made Oedpia look more closely at its outside, when it arrived. At

first she didn't see. It was an ordinary Muchoesque envelop, swiped from

the [radio] station [at which Mucho worked], ordinary airmail stamp, to

the left of the cancellation a blurb put on by the government, REPORT

ALL OBSCENE MAIL TO YOUR POTSMASTER.

A set up within a set up: "At first she didn't see." An "economical"

abbreviation, surely: "At first see didn't see [the blurb]." But also,

if only for a flashing moment, there's a suggestion that Oedipa

was blind ("she didn't see [at all]") and then, jarred by the comical

spelling mistake ("potsmaster" for "postmaster"), regained her sight -- a

kind of reversal of the fortunes of Sophocles' Oedipus.

When told of the glaring mistake, Metzger makes a grim joke about two

different kinds of delivery systems that are monopolized by the federal

government (postal, and nuclear weaponry). "So they [the government]

make misprints," Metzger said, "let them. As long as they're careful

about not pressing the wrong button, you know?" Yes, of course: nuclear war

would be an "obscenity" too horrible to report to and, in any case,

well beyond the jurisdiction of the Postmaster General of the United

States of America.

In the very next sentence ("It may have been that same evening that

they happened across The Scope, a bar out on the way to L.A., near the

Yoyodyne [weapons delivery] plant"), the narrator conveys us, post-haste,

to the next stop along the route. While having a drink inside The

Scope, Oedipa witnesses what looks like "mail call" along "an

inter-office mail run" for employees at Yoyodyne. Immediately

afterwards, Oedipa enters the ladies' bathroom, where, "among lipsticked

obscenities," she quickly "noticed the following message, neatly indited in engineering lettering" (emphasis added):

'Interested in sophisticated fun? You, hubby, girl friends.

The more the merrier. Get in touch with Kirby, through WASTE only, Box

7391, L.A.'

It's a "personals" ad, a commonplace, a cliche: horny geek looking for sex.

But there's something else going on, as well. The word "indited" means

more than just written or engraved: it's usually applied to speeches,

poems, announcements and other "open letters," addressed to one-and-all.

It is at variance with the exclusivity of "WASTE only." And what is

WASTE? An economical or abbreviated rendering of W.A.S.T.E. (Later on,

Oedipa -- by pronouncing it "like a word, waste" -- will alienate a user

of the system, who explains, behind "a mask of distrust," "it's

W.A.S.T.E., lady, an acronym, not 'waste.'" The acronym "posts" or

stands for the slogan "We Await Silent Tristero's Empire," but still

remains a pun on "waste," on yet another collection, sorting and

delivery system controlled by the goverment. Looking for and finally

finding a W.A.S.T.E. mailbox, Oedipa sees "a can with a swinging

trapezoidal top, the kind you throw trash in: old and green, nearly four

feet high. On the swinging part were hand painted the initials

W.A.S.T.E. She had to look closely to see the periods between the

letters.")

Back in The Scope's bathroom, the narrator says: "Beneath the notice

[the personals ad], faintly in pencil, was a symbol she'd never seen

before, a loop, triangle and trapezoid [...]. It might be something

sexual [a depiction of genitalia], but somehow she doubted it. She found

a pen in her purse and copied the address and symbol [a post horn with a

mute inserted into its bell] in her memo book, thinking: God,

hieroglyphics." She might have thought, God, again with the hierogylphics.

Oedipa had already divined "a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning"

in the printed circuits (or "cards") in transistor radios, in the

"ordered swirl" of houses and streets in South California, and mostly

vidily in Pierce Inverarity's Fangoso Lagoons, a "new housing

development," which

was to be laced with canals with private landings for power boats, a

floating social hall in the middle of an artificial lake, at the bottom

of which lay restored galleons, imported from the Bahamas; Atlantean

fragments of columns and friezes from the Canaries; real human skeletons

from Italy [...] A map of the place flashed onto the screen, Oedipa

drew a sharp breath [...] Some immediacy was there again, some promise

of hierophany: printed circuit, gently curving streets, private access

to the water, Book of the Dead.

As soon as Oedipa returns from The Scope's bathroom, one of the bar's

patrons "had this funny look on his face" and says to her, "You weren't

supposed to see that." There's a moment of confusion. Did the

bar-patron (Mike Fallopian of the Peter Pinguid Society) mean the

W.A.S.T.E. personals ad, or the inter-office mail run? Did he, having

X-ray machines for eyes, happen to see Oedipa noticing the W.A.S.T.E.

personals ad, right through the bathroom wall? No, of course not; it would be paranoid to think so.

The very next sentence (the narrator is keeping the plot moving): "He

[Fallopian] had an envelop. Oedipa could see, instead of a postage

stamp, the handstruck initials PPS [Peter Pinguid Society]." Fallopian,

trying to reassure Oedipia that "it's not as rebellious as it looks,"

shows her the innocent, post card-like contents of a letter he'd just

received through the W.A.S.T.E. system.

"Dear Mike. How are you? Just thought I'd drop you a note. How's your

book coming? Guess that's all for now. See you at The Scope."

Here it is, then: the message on the post card that is The Crying of Lot 49.

(All we need now is the address, and the stamp, and it will be ready

for the post). Pynchon's narrator explains what Mike Fallopian's book is

about:

[It's] a history of private mail delivery in the U.S., attempting to

link the Civil War to the postal reform movement that had begun around

1845. [Fallopian] found it beyond simple coincidence that in of all

years 1861 the federal government should have set out on a vigorous

suppression of those independent mail routes still surviving the various

Acts of '45, '47, '51 and '55, Acts all designed to drive any private

competition into financial ruin. He saw it all as a parable of power,

its feeding, growth and systematic abuse.

Though he may be paranoid -- for what lies "beyond simple

coincidence," other than conspiracy? -- this Mike Fallopian is

definitely "on the right track," both historically (the international

postal reform movement of the 1840s) and ideologically (the parable of

power). Or at least he's traveling in the same route taken by Jacques

Derrida's The Post Card, in which the following passage appears.

[Y]es, in the "modern" period the country of the Reformation [Germany]

has played a rather important role, it seems to me in postal reform

[...] No, I don't have any big hypothesis about the conjoint development

of capitalism, Protestantism, and postal rationalism, but all the same,

things are necessarily linked. The post is a banking agency. Don't

forget that in the great reformation of the "modern" period another

great country of the Reformation [England] played a spectacular role: in

1837 Rowland Hill publishes his book, Post-Office Reform: Its Importance and Practicability.

He is an educator; and a reformer of the fiscal system. What was he

proposing? the stamp, my love, what would we have done without it? The

sticking stamp, that is, the uniformization of payment, the general

equivalent of the tax, above all the bill before the letter, the payment

in advance (the uniform rate and a system of prepayment, which were adopted in 1840 after great popular agitation).

And so, at the center of it all: pre-paid postage stamps. The

"reformed" Post Office insists on their universal use, and "underground"

groups like the Peter Pinguid Society and the Tristero refuse to use

them at all and, on occasion, make mocking counterfeits of "official"

ones. And, at the center of the plot in The Crying of Lot 49, a whole collection of pre-paid postage stamps.

* * * *

With the opening of Mike Fallopian's book, about a quarter of the way through The Crying of Lot 49,

Pynchon's narrator has completed the necessary detours. We are ready to

precede to the heart of the matter: "So began, for Oedipa, the languid,

sinister blooming of the Tristero." No -- a hesitation on the

narrator's part -- "blooming" mixes the metaphor of the mantle (the

tapestry). And so he tries again:

So began, for Oedipa, the languid, sinister blooming of the Tristero. Or

rather, her attendance at some unique performance, prolonged as if it

were the last of the night, something a little extra for whoever'd

stayed this late. As if the breakaway gowns, net bras, jeweled garters

and G-strings of historical figuration that would fall away were layered

dense [...]; as if a plunge toward dawn indefinite black hours long

would indeed be necessary before the Tristero could be revealed in its

terrible nakedness.

This second try is a complex re-presentation, change and expansion of

the novella's central images (metaphors): the mantle isn't simply a

form of magic that covers parts of the world, but "historical

figuration" (the embroidery of experts), which doesn't seem to be magic

at all, but a neutral science; and it (the mantle) doesn't simply cover

the naked body of the Earth, but also the naked body of the Tristero

conspiracy.

Note as well the apocalyptic tone: "the last of the night," the

"late" hours, the "indefinite black hours," the "terrible" nakedness of

the final truth. A haunting certainly, but not by the shadow or

spectre of nuclear war, something in the looming future, but by the end

of a long-standing epoch. The end of the post (symbolized by the muted

post horn) and the beginning of the telephone, which Pynchon's narrator

refers to as "the horn." Derrida mourns the entire epoch from Socrates

to Freud: "We are writing the last letters [...] We are taking the last correspondance

[letters and correlations]. Soon there will be no more of them.

Eschatology, apocalypse, and teleology of epistles themselves. For the

same reason there will be no more money. I mean bills or coins, and no

more stamps. Of course the [mechanical] technology which is replacing

all that had already begun to do so for a very long time [...] It will

no longer be writing that will be transported, but the perforated card,

microfilm, or magnetic tape. The day will come that, thanks to the 'telepost,' the fundamentals will be transmitted by wire starting from the user's computer."

Incredibly, Pynchon's narrator, instead of moving on to Pierce's

stamp collection (his "proper" destination), does something

uneconomical, even wasteful. He goes backwards, back to the very

beginning, and tries to start the story again. "The beginning of that

peformance [the striptease-like denuding of the Tristero] was clear

enough. It was while she and Metzger were waiting for ancillary letters

to be granted representatives in Arizona, Texas, New York and Florida,

where Inverarity had developed real estate, and in Delaware, where he'd

been incorporated" (emphasis added). Different, but the same story:

waiting for the arrival of letters, more letters, more waiting.

This new thread (the striptease) leads Oedipa to the play The Courier's Tragedy,

a fictional Jacobean revenge play that alludes to the Tristero

conspiracy. From there, the yarn leads to a theatrical performance of

the play, the director of that particular performance (Randy Driblette),

the play's author (a fictional 17th century playwright named Richard

Wharfinger), the script Driblette used (there are, of course, several

different editions of the play, some of which are textually "corrupt,"

one of which is "obscene"), the bookstore at which Driblette purchased

his copy (Zapf), the publisher of that "unaccountable" edition (Lecturn,

based in Berkeley), the author of a preface to one of the rival

editions (Emory Bortz), etc etc.

Like the play-within-the-play in Shakespeare's Hamlet, The Courier's Tragedy

is used to both further and comment upon the plotting of the novella

itself. It is presented as "the landscape of evil Richard Wharfinger had

fashioned for his 17th-century audiences, so preapocalyptic,

death-wishful, sensually fatigued, unprepared, a little poignantly, for

the abyss of civil war that had been waiting, cold and deep, only a few

years ahead of them." There are three civil wars in perspective

here: the English Civil War, circa 1648; the American Civil War, circa

1861 (cf. Mike Fallopian's book); and the (Second) American Civil War,

circa 1965 (the "counter-culture" of Southern California).

Postal systems are central to the plot of The Courier's Tragedy.

(Once again, "the plot" involves dramatic action, burial place, and

conspiracy.) The "courier" of the play's title is Niccolo, who,

Pynchon's narrator says,

is hanging around the court of his father's murderer, Duke Angelo, and

masquerading as a special courier of the Thurn and Taxis family, who at

the time held a postal monopoly throughout most of the Holy Roman

Empire. [Niccolo's father had been the Duke of Faggio; Angelo had him

replaced by Pasquale.] What he [Niccolo] is trying to do, ostensibly, is

develop a new market, since the evil Duke of Squamuglia [Angelo] has

steadfastedly refused, even with the lower rates and faster service of

the Thurn and Taxis system, to employ any but his own messengers in

communicating with his stooge Pasquale over in neighboring Faggio. The

real reason Niccolo is waiting around is of course to get a crack at the

Duke.

In Act IV, Angelo learns that Pasquale has been assassinated, and

that someone named Gennaro has raised an army and declared himself

"interim head of state until the rightful Duke, Niccolo, can be

located." Angelo writes a letter, all the while "explaining to the

audience but not to the good guys, who are still ignorant of recent

developments, that to forestall an invasion from Faggio, he must assure

Gennaro with all haste of his good intentions." When the letter is

completed, Angelo (taking no chances) doesn't give it to one of his own

couriers, but summons someone from Thurn and Taxis to deliver it.

Niccolo shows up, takes the letter and goes off to deliver it to

Gennaro. Angelo doesn't realize that the courier was Niccolo in

disguise, and Niccolo doesn't know that the letter's contents pertain to

him personally. Neither Angelo nor Niccolo realize that the subject of

the letter and its deliverer are one and the same person.

Angelo is the first to make the connection. As soon as he does, he

"orders Niccolo's pursuit and destruction." Once again, Angelo doesn't

use his own men, but he doesn't summon Thurn and Taxis a second time.

Instead, he turns to the Tristero, Thurn and Taxis's sworn enemy. Just

before Niccolo is overtaken and killed by Tristero assassins, he opens

up the letter he's been carrying. Reading aloud, he makes "sarcastic"

comments about what "is blatantly a pack of lies devised to soothe

Gennaro until Angelo can muster his own army." But when Gennaro arrives

on the scene, and reads the letter aloud, "it is no longer the lying

document Niccolo read us excerpts from at all, but now miraculously a

long confession by Angelo of all his crimes [...] In the presence of the

miracle, all fall to their knees, bless the name of God, mourn Niccolo,

vow to lay waste to [Angelo's Dukedom of] Squamuglia." But who

performed the miracle? Who re-wrote and re-sealed the letter? If not the

Tristero, then whom? God?!

Oedipa's pursuit of the truth behind the text of The Courier's Tragedy,

though it turns up several tantalizing clues, takes her further and

further away from Pierce's stamp collection. Eventually, there's a kind

of break-down or catastrophe. At a particular place in the novella, the

narrator sets his readers' sights on a specific destination ("The publisher's up in Berkeley," Oedipa thinks to herself; "Maybe I'll try them directly") and then sends them somewhere else

("next day she drove out to Vesperhaven House, a home for senior

citizens"). Seven pages later, without noticing the lengthy and quite

extraordinary detour he's just pursued, the narrator takes up where he

left off, as if nothing unusual has happened ("She [Oedipa] found the

Lecturn Press in a small office building on Shattack Avenue").

But something unusual did happened. Jacques Derrida might say

that Pynchon intentionally and openly tried to imitate or import into

the form of his narration the truth of all postal operations. Drawing

upon both philosophy (historical figuration) and common sense (personal

experience), Derrida states:

The condition for [the letter] to arrive is that it ends up and even

that it begins by not arriving [...] A letter can always not arrive at

its destination, and that therefore it never arrives. And this is really

how it is, it is not a misfortune, that's life [...] To post is to send

by "counting" with a halt, a relay, or a suspensive delay, the place of

the mailman, the possibility of going astray and of forgetting [...] A

strike [by the employees], or even a sorting accident, can always delay

indefinitely, lose without return.

For these reasons, Derrida is fascinated by "dead letters," pre-paid

missives that never arrive, that enter into and remain in the postal

system.

"Dead Letter Office. -- Letters or parcels which cannot be delivered,

from defect of address or other cause, are sent to the Division of dead

letters and dead parcels post. They are carefully examined on both front

and back for name and address of the sender; if these are found, they

are returned to the sender. If the sender's address is lacking, they are

kept for a period, after which dead letters are destroyed, while dead

parcels are sold at auction." I ask myself, and truly speaking they

could never give me a satisfactory answer on this question, how they

distinguish a letter and a parcel, a dead letter and a dead parcel, and why they did not also sell a so-called dead letter at auction.

All this certainly goes a long way in The Crying of Lot 49,

the ultimate destination of which is a dead man's stamp collection,

parceled and ready to be sold at an auction. But there must be more in

play than just that. Note the abruptness of and confusion caused by the

beginning of the narrator's 7-page-long detour.

"Wait," [Oedipa] said, having just got an idea, "the publisher's up

in Berkeley. Maybe I'll try them directly." Thinking also she could

visit John Nefastis.

She had caught sight of the historical marker only because she'd gone back, deliberately,

to Lake Inverarity one day, owing to this, what you might have to call,

growing obsession, with "bringing something of herself" -- even if that

something was just her presence -- to the scatter of business interests

that had survived Inverarity. She would give them order, she would

create constellations; next day she drove out to Vesperhaven House, a

home for senior citizens that Inverarity had put up around the time

Yoyodyne came to San Narciso. (Emphasis added.)

In sharp contrast to Oedipa's commitment to giving "order" (Taxis)

and constellation-like coherence or legibility to Inverarity's

"scatter," the narrator here creates disorder, a sense of dislocation,

by deliberately going back and forth very quickly. Back to Lake

Inverarity, where, by accident, "on the other side of the lake at

Fangoso Lagoons," Oedipa happened to see "the historical marker," which

proclaimed:

On this site, in 1853, a dozen Wells, Fargo men battled gallantly with a

band of masked marauders in mysterious black uniforms. We owe this

description to a post rider, the only witness to the massacre, who died

shortly after. The only other clue was a cross, traced by one of the

victims in the dust. To this day the identities of the slayers remains shrouded in mystery. (Emphasis added.)

And then, suddenly forward, not to Berkeley and the Lecturn Press, but to Vesperhaven House, a destination that has arrived completely unannounced and totally unexpected.

On the day of Oedipa's visit, neither the residents of Vesperhaven nor

even Pynchon's own readers knew or were told that she was coming. She

had no real reason to go there, in the first place: Yoyodyne is only

peripherally involved in the Tristero conspiracy, and had already been

covered. Oedipa just wandered into Verperhaven one fine day, without

knowing who, exactly, she wanted to talk to. She might have met no one

on that particular day; the whole trip might've ended up a waste of time and effort.

Miraculously, the person Oedipa is lucky enough to meet isn't a "character" in the story, or at least hadn't yet been named, mentioned or alluded to.

In its front recreation room she [Oedipa] found sunlight coming in it

seemed through every window; an old man nodding in front of a dim Leon

Schlesinger cartoon show on the tube; and a black fly browsing along the

pink, dandruffy arroyo of the neat part in the old man's hair. A

fat nurse ran in with a can of bug spray and yelled at the fly to take

off so she could kill it. The cagey fly stayed where it was. "You're

bothering Mr Thoth," she yelled at the little fellow. Mr Thoth jerked

awake, jarring the loose the fly, which made a desperate scramble for

the door. The nurse pursued, spraying poison. "Hello," said Oedipa. "I

was dreaming," Mr Thoth told her, "about my grandfather. A very old man,

at least as old as I am now." (Emphasis added.)

Is it a mere "coincidence" or "accidental correlation" that, in ancient Egyptian mythology, Thoth

was the inventor of numbers and writing (hieroglyphics)? Or that, in

ancient Greek mythology, Thoth was identified with Hermes, herald and

messenger (mailman) of the gods? No, these correlations can't be

accidental, they must be intentional, because this "Mr Thoth" not only

knows about the Tristero, but has definite proof of its existence.

"A Spanish name," Mr Thoth said, frowning, "a Mexican name. Oh, I can't

remember. Did they write it on the ring?" He reached down to a knitting

bag by his chair and came up with blue yarn, needles, patterns, finally a

dull gold signet ring. "My grandfather cut this from the finger of one

of them he killed. Can you imagine a 91-year-old man so brutal?" Oedipa

stared. The device on the ring was once again the WASTE symbol.

Another stunning coincidence: dangling at the end of Mr

Thoth's "blue yarn" is Plato's version of the story of the ring of

Gyges. As Marc Shell points out in The Economy of Literature, the

story of Gyges had been told by many ancient writers, including

Herodotus, Xanthos, Anacreon, Plutarch, Cicero, Archilochus, and Horace.

(Modern writers who have told the story include Montaigne, La Fontaine,

Rousseau, Gautier, Gide and Tolkien.) But Plato was the first ancient

to insist that Gyges was able to commit murder, seize control of Lydia,

and become a tyrant (indeed, the very first tyrant of the ancient world)

because he possessed a magic solid-gold ring, which (another

coincidence!) he'd stolen from the finger of a corpse that'd been

brought up from underground by an earthquake. Is it yet another coincidence that, in Spanish, arroyo means "gulch," but also "mine shaft" (a place from which underground gold is brought to the surface)?

In Marc Shell's account, Plato introduced his novel hypothesis

because Gyges was the first ruler to mint coins and use them as money.

"Rings played several roles in the economic development of money [in

ancient Greece]," Shell notes. Before the invention of coined money,

rings were among the most commonly used symbola (valued items cut

in half and divided between parties who'd entered into a contract,

which was thus both sealed and "symbolized" by the cutting). Some of the

very first coins were actually ring-coins, coins that could circulate

and be worn as rings. And, perhaps most importantly, the seals or

writing on the rings of kings were sometimes used to mint coins (and, it

shouldn't go without mentioning, to seal and provide authentification

for the letters conveyed by the king's couriers).

And there's the hitch or gather in the fabric: you can't separate the

monetary system from the postal system. Mr Thoth's ring (the ring of

Gyges) joins them together. Recall what Derrida said: "The post is a

banking agency." Perhaps there's no need to remind Thomas Pynchon, who

wrote The Crying of Lot 49 the same year (1965) that the U.S.

Post Office announced it was closing all of its postal savings banks,

which had been in operation since 1910. There should have been no

need to remind Oedipa of the connection between letters and money.

According to the narrator, "the probate court," after evaluating "in

dollars [...] how much did stand in her way" -- that is, how likely she

was to bail out of her responsibilities to the court -- had required

Oedipa to "post" a bond. But, no: Oedipa needs to be reminded, again.

That, precisely, is her function, her primary purpose: to remember. She

tells herself: "I am meant to remember. Each clue is supposed to have

its own clarity, its fine chances for permanence." But then, the

narrator says, "she wondered if the gemlike 'clues' were only some kind

of compensation. To make up for having lost the direct, epilectic Word,

the cry that might abolish the night" (emphasis added).

After the miraculous appearance, deus ex machina, of Mr Thoth, Oedipa searches out Mike Fallopian. What does he

make of the historical marker she'd accidently seen? "There's no way to

trace it, unless you want to follow up an accidental correlation, like

you got from the old man," he tells Oedipa, trying to dissuade her from

pursuing the matter any further. Oedipa, ignoring Fallopian's use of the

word "accidential," asks him in response: "You really think it's a

correlation?" It's really a double correlation: a correlation

between the "band of masked marauders in mysterious black uniforms" and

the couriers of the Tristero; and a correlation between the incident

commemorated by the marker and the incident remembered by Mr Thoth (his

grandfather is the post rider who survived to tell the tale). And, of

course, there is also a pun, which Pynchon doesn't hesitate to make, on

"relation," as in family relations or "lines" of kinship. Oedipa, the

narrator says, "thought of how tenuous it was, like a long white hair,

over a century long. Two very old men [grandfather and grandson]. All

these fatigued brain cells between herself and the truth."

Even the narrator thinks that Oedipa should be getting the

hang of the weave (the plot) by now. "If she'd thought to check a couple

lines back in the Wharfinger play," he says, "Oedipa might have made

the next connection by herself." But she didn't. "As it was she got an

assist from Genghis Cohen," "the most eminent philatelist in the L.A.

area," who'd been retained by Metzger, "acting on instructions in the

will," "to inventory and appraise Inverarity's stamp collection [...]

for a percent of his valuation." In this arrangement, a lot, Lot 49

itself, depends on Cohen's "values." If he is an honest man, he will

correctly appraise or evaluate the collection, and get paid "properly,"

according to the stipulated percent (which of course can either be large

or small). But if he's a dishonest or corrupt man, he can intentionally

overestimate the collection's value and thereby collect more money than

he would have otherwise. It's called a "con game," a manipulation of

"confidence." (At the end of the novella, when Oedipa spots him at the

auction, Cohen looks "genuinely embarassed," and knows exactly why he

shouldn't be there: "Please don't call it a conflict of interests," he

tells her. "There were some lovely Mozambique triangles I couldn't quite

resist." He's "conned" himself into believing he's not corrupt, much in

the same way that Oedipa had once "conned herself into the curious,

Rapunzel-like role of pensive girl.")

An indefinite time after her encounter with Mr Thoth ("One rainy

morning"), but still within the narrator's unaccountable, 7-page-long

interruption, "Oedipa got rung up by this Genghis Cohen, who even over

the phone she could tell was disturbed. 'There are some irregularities,

Miz Maas,' he said. 'Could you come over?'" Since this is the

destination to which the entire narrative so far has been heading,

Oedipa gets in her car right away (no delays) and drives straight to

Cohen's office (no detours). Once she's arrived, however, Cohen serves

her "real homemade dandelion wine," and tells her, "I picked the

dandelions in a cemetary, two years ago. Now the cemetary is gone. They

took it out for the East San Narciso Freeway." It's like she's hearing a

post horn, heralding a delivery. Then she blacks out.

She could, at this stage of things, recognize signals like that, as the

epilectic is said to -- an odor, color, pure piercing grace note

announcing his seizure. Afterward it is only this signal, really dross,

this secular announcement, and never what is revealed during the attack,

that he remembers. Oedipa wondered whether, at the end of this (if it were supposed to end),

she too might not be left with only compiled memories of clues,

announcements, intimations, but never the central truth itself, which

must somehow each time be too bright for her memory to hold; which must

always blaze out, destroying its own message irreversibly, leaving an

overexposed blank when the ordinary world came back [...] She glanced

down the corridor of Cohen's rooms in the rain and saw, for the very

first time, how far it might be possible to get lost in this. (Emphasis

added.)

When, exactly, does Oedipa's seizure end? Is it even supposed to end?

Did it end as soon as or a few moments after Cohen started explaining

what he's found? After she leaves his office? After the narrator's

seven-page-long interruption has ended? There's no telling.

The "disturbing" news is the fact that Pierce's stamp collection is

corrupt or, rather, contains several corrupt stamps. Cohen shows Oedipa

"a U.S. commemorative stamp, the Pony Express issue of 1940, 3 cents

henna brown," which, like many other stamps, uses a watermark to verify

and reassure that the stamp itself is legitimate, and to discourage or

trap counterfeiters. But this particular watermark has the W.A.S.T.E.

symbol (a muted post horn) worked into it. "It's obviously a

counterfeit," Cohen tells Oedipa. "Not just an error." There are eight

"counterfeits" in all, each of which, Cohen reports, has "an error like

this, laboriously worked into the design, like a taunt. There's even a

transposition -- U.S. Potsage, of all things."

As Cohen himself notes, "The question is, who did these?" Asked

another way, "Who would want to taunt the U.S. Post Office?" Several

possibilities immediately come to mind: bored, disgruntled or striking

postal employees (insiders); agents from competing postal systems,

possibly the Tristero (infiltrators); and enemies of the United States

government itself, not just its Post Office (in wartime, even a "cold

war," an obviously counterfeit stamp can be circulated in the hopes that

it will destroy public confidence in both the financial and political

legitimacy of the enemy's leadership).

In any case, Oedipa doesn't understand. She thinks that a counterfeit

stamp will be like a counterfeit banknote: valuable only when

overlooked, and worthless when properly identified. "Then it isn't worth

anything," she guesses when Cohen first uses the word "counterfeit."

But she's wrong: a counterfeit stamp remains (valuable), after it has

been identified and exposed. Doubly corrupt, it can be sold or auctioned

off after being seized, while a counterfeit banknote is always

destroyed after being seized. "You'd be surprised how much you can sell

an honest forgery for," Cohen tells Oedipa. "Some collectors specialize

in them." And so this "disturbing" news is actually very good news. It

means that Pierce's stamp collection is probably worth a great deal more

than originally thought, which in turn means that Cohen's fees will in

turn be much higher. The government -- not only the postal inspectors,

but the probate court, as well -- should be notified of these

discoveries. "Do we tell the government, or what?" innocent Oedipa asks

Cohen, who, "nervous or suddenly in retreat," replies, "No, I wouldn't.

It isn't our business, is it?" No, apparently not: Cohen's "business"

lies in not reporting things (sources of income, conflicts of interest, criminal activity) to the government.

So ends the 7-page-long interruption and the first half of the

novella. The transition back to the main thread (the beginning of

Chapter 5) is yet another "postal" relay. A kind of reverse of the

others, this one -- instead of addressing us properly (to Lecturn Press,

in Berkeley) and then sending us to the wrong destination (Vesperhaven)

-- addresses us improperly and then sends us to the right destination:

"Though her next move should have been to contact Randolph Driblette

again, she decided instead to drive up to Berkeley."

* * * *

Marc Shell notes that "the ring of Gyges is a hypothesis that is discarded in the philosophical course" of the Republic,

in which Socrates eventually declares "we have proved [...] that the

soul ought to do justice whether it possess the ring of Gyges or not."

Shell also notes that "the conclusion that the ring of Gyges is finally a

bad thing and ought (if found) to be thrown away influenced many

political philosophers after Plato," especially Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

But what about Thomas Pynchon? He's got the ring of Gyges; he got it

from Tolkien; Mr Thoth (even) showed it to Oedipa. But what's Pynchon

going to do with it: use it and be corrupted, or throw it away? No;

no excluded middles. "[Oedipa] had heard all about [them]; they were

bad shit, to be avoided." Pynchon is going to try to have it both ways:

he's gonna keep the ring, let Oedipa use it in her search for the truth,

but only for a little while; then he'll take it back from her and cashier it.

Cashiered is the name of a disaster movie that Metzger starred

in when a child, and "kasher" (a punning cross between cashier and

kosher) is part of his schtick, his "come on" to women: "My mother was

really out to kasher me, boy, like a piece of beef on the sink, she

wanted me drained [of blood] and white. Times I wonder [...] if she

succeded. It scares me. You know what mothers like that turn their male

children into." In our usage of the word, "cashiering" means

dismissing the ring (as one might dismiss a disgraced person from a high

post), rejecting and discarding it (as one might refuse a ring

consummating or offered in proposal of a marriage), and annuling and

discharging it (as one might "break" a contractual agreement, vow or

bond).

For most of the second half of the novella, Oedipa is or at least

feels "invisible." As a result, she is able to go to commonplace

locations and see and hear "secret," even forbidden (Oedipal), things.

Out at the airport Oedipa, feeling invisible, eavesdropped on a poker

game whose steady loser entered [posted] each loss neat and

conscientious in a little balance-book decorated inside with scrawled

post horns [...] Catching a TWA flight to Miami was an uncoordinated boy

who planned to slip at night into aquariums and open negotiations with

the dolphins, who would succeed man. He was kissing his mother

passionately goodbye, using his tongue. "I'll write, ma," he kept

saying. "Write by WASTE," she said, "remember. The government will open

it if you use the other. The dolphins will be mad." "I love you, ma," he

said. "Love the dolphins," she advised him. "Write by WASTE." So it

went. Oedipa played the voyeur and listener.

Thanks to the powers of the ring, Oedipa, "with her own eyes,"

"verified a [whole] WASTE system: [she'd] seen two WASTE postmen, a

WASTE mailbox, WASTE stamps, WASTE cancellations. And the image of the

muted post horn all but saturating the Bay Area" (emphasis

added). She was also able "to fit together" a credible "account" of how

the Tristero organization began, back in the 16th century, as a rival to

the (quite real) Thurn and Taxis postal monopoly, the symbol of which

was an open or unmuted post horn. But, most importantly, Oedipa was to

able to understand how and why the Tristero survived, how and why it

became today's W.A.S.T.E.

For here were God knew how many citizens, deliberately choosing not to

communicate by U.S. Mail. It was not an act of treason, nor possibly

even of defiance. But it was a calculated withdrawal, from the

life of the Republic, from its machinery. Whatever else was being denied

them out of hate, indifference to the power of their vote, loopholes,

simple ignorance, this withdrawal was their own, unpublicized, private. Since they could not have withdrawn into a vacuum (could they?), there had to exist the separate silent, unsuspected world. (Emphasis added.)

There's been an exchange of "withdrawals" that, tragically, leaves a

kind of vacuum in the middle. Ignored, denied and excluded from the

Republic by the rich and powerful people of America, the poor and

powerless have responded by going silent or only speaking in code. But,

on both sides of the exchange, the withdrawals keep something back or

take away something with them. The "machinery" of America's putatively

democratic society (despite the absence of real citizens) keeps its

"life," and the network of the excluded (despite being given a kind of

death sentence) keep their dignity and sense of self as people who

"belong." Indeed, they identify with D.E.A.T.H.: "Don't Ever Antagonize

the Horn" is a graffito Oedipa sees accompanying a muted post horn.

Towards the end of the novella, Oedipa herself suddenly starts to withdraw from or cry off

her quest for the truth, though she risks losing her bond and having

the probate court revoke her "letters testamentary." Perhaps the

corruption of the ring has begun to seize her (); perhaps the ring's no

longer in her possession (Pynchon having withdrawn it). Instead of being

curious, even zealous, she becomes "anxious that her revelation not

expand beyond a certain point. Lest, possibly, it [like the ocean] grow

larger than she and assume her to itself." She tells one of her sources

of information, "It's over, they've saturated me. From here on

I'll only close them out. You're free. Released" (emphasis added). And

then, "her isolation complete," Oedipa "tried to face toward the sea.

But she'd lost her bearings." She, too, has been "released," set "free."

The indefinitely long period of mourning for Pierce Inverarity --

seven days? seven weeks, that is, 49 days? whatever -- it's over. Images

of Varo's Bordando el Manto Terrestre and "the continuous tradition" of "the weave itself" itself are clearly recalled at the crucial moment:

San Narciso at that moment lost (the loss pure, instant, spherical, the

sound of stainless orchestral chime held among the stars and struck

lightly), gave up its residue of uniqueness for her; became a name

again, was assumed back into the American continuity of crust and mantle. Pierce Inverarity was really dead. (Emphasis added.)

Oedipa can now see what had previously escaped her notice:

Every access route to the Tristero could be traced back to the

Inverarity estate [...] The whole shopping center that housed Zapf's

Used Books [...] had been owned by Pierce. Not only that, but the Tank

Theatre [where Driblette's production of The Courier's Tragedy had been staged], also [...] Even Emory Bortz, with his copy of Blobb's Peregrinations

(bought, she had no doubt he'd tell her in the event she asked, also at

Zapf's), taught now at San Narciso College, heavily endowed by the dead

man. Meaning what? That Bortz, along with Metzger, Cohen, Driblette,

Koteks, the tattoed sailor in San Francisco, the W.A.S.T.E. carriers

she'd seen -- that all of them were Pierce Inverarity's men? Bought? Or

loyal, for free, for fun, to some grandiose practical joke he'd cooked

up, all for her embarassment, or terrorizing, or moral improvement?

Oedipa has realized that the Sphinx-like riddle of the Tristero ("why me?") might not be a conspiracy, but a hoax,

and that it isn't being played on the U.S. government and its

Potsmaster, but, once again, on her personally and her alone. Thinking

aloud for Oedipa, the narrator speculates on the following possibility:

"A plot has been mounted against you, so expensive and elaborate,

involving items like the forging of stamps, and ancient books, constant

surveillance of your movements, planting of post horn images all over

San Francisco, bribing of librarians, hiring of professional actors and

Pierce Inverarity only knows what-all besides, all financed out of the

estate, in a way either too secret or too involved for your non-legal

mind to know about even though you are co-executor, so labyrinthine that

it must have meaning beyond a practical joke."

Perhaps Pierce's cryptic motivations concerned not so much Oedipa's

behavior as what she symbolized: "Though he had never talked business

with her, she had known it to be a fraction of him that couldn't come

out even, would carry forever beyond any decimal place she might name;

her love, such as it had been, remaining incommensurate with his need to

possess, to alter the land, to bring new skylines, personal

antogonisms, growth rates into being." It's also possible that the hoax

wasn't on Oedipa so much as on Death:

She just didn't know. He himself [Pierce] might have discoverd The Tristero, and encrypted that into the will, buying into just enough

to be sure she's find it. Or he might even have tried to survive death,

as a paranoia; as a pure conspiracy against someone he loved. Would

that breed of perversity prove at last too keen to be stunned even by

death, had a plot finally been devised too elaborate for the dark Angel

to hold at once, in his humorless vice-president's head, all the

possibilities of? Had something slipped through and Inverarity by that

much beaten death? (Emphasis added.)

And so, "the plot" of The Crying of Lot 49 comes down to four

distinct, mutually exclusive possibilities. The Tristero/WASTE system is

either (1) a conspiracy against the pre-paid postal stamp or (2) a hoax

that counterfeits such a conspiracy; and if "the plot" is a hoax, the

motivation for perpetrating it is either (3) pay-back for an unwanted

remainder (an "odd" fraction of Pierce's personality, or Oedipa's

"incommensurate" love), or (4) an investment in a highly prized

remainder (life after death, or immortality). There's a thread that runs

through or connects each one: money, which doesn't simply

corrupt people, their motivations and their behavior; it also corrupts

their minds, thinking and language. It stamps everything.

Pynchon's narrator also comes up with four symmetrical possibilities, but his list varies from ours.

Either (1) you [Oedipa] have stumbled [...] onto a network by which X

number of Americans are truly communicating whilst reserving their lies,

recitation of routine, arid betrayals of spiritual poverty, for the

official government delivery system [...] Or (2) you are hallucinating

it. Or (3) a plot has been mounted against you, so expense and elaborate

[...] that it must have meaning beyond a practical joke. Or (4) you are

fantasying some such plot, in which case you are a nut, Oedipa, out of

your skull. (Numbers added.)

Note that the narrator has substituted psychology

(possibilities 2 and 4) for money. As a matter of fact, the word "money"

is only used once in the whole novella: "No one could begin to trace

it," the narrator says of Driblette's decision to add two lines to The Courier's Tragedy.

"A hundred hangups, permuted, combined -- sex, money, illness, despair

with the history of his time and place, who knew." Money is just one

"problem" or thread among many, and not the principle or dominant one.

Who has the authority to choose one of these possibilities and

exclude the others, to make a "finding of fact" or other legally

binding decision? As co-executor of Pierce's estate, Oedipa Maas

does. But, "saturated," she's "freed" and "released" those who had felt

bound to give information, and has vowed to "close them out" thereafter.

Who does that leave, next in the order of succession? The narrator.

And he does not fail to deliver or deposit Oedipa at the auction,

though she is, like Wharfinger's 17th century audiences, "death-wishful,

sensually fatigued, [and] unprepared" for the drama about to unfold.

To make sure that the estate makes as much money as possible and that

there's no conflict of interest (no "hidden" deals, no price-fixing),

the stamps are auctioned off, in a public ceremony, rather than simply

sold in the usual fashion, i.e., privately. Despite the fact that the

auction is open to "you, hubby, girl friends," anyone, the mood is exclusive ("WASTE only," men only).

The men inside the auction room wore black mohair and had pale, cruel

faces. They watched her [Oedipa] come in, trying each to conceal his

thoughts. Loren Passerine [the auctioneer], on his podium, hovered like a

puppet-master, his eyes bright, his smile practiced and relentless. He

stared at her, smiling, as if saying, I'm surprised you actually came.

Oedipa sat alone, toward the back of the room [...] An assistant closed

the heavy door on the lobby windows and the sun. She heard a lock snap

shut; the sound echoed a moment. Passerine spread his arms in a gesture

that seemed to belong to the priesthood of some remote culture; perhaps

to a descending angel. The auctioneeer cleared his throat. Oedipa

settled back, to await the crying of Lot 49.

This scene, the novella's very last, has its echo in Derrida's The Post Card.

When I enter the post office of a great city I tremble as if in a sacred

place, full of refused, promised, threatening pleasures. It is true

that inversely I often have a tendency to consider the great temples as

noisy sorting centers, with very agitated crowds before the distribution

begins, like the auctioning of an enormous courrier. Occasionally the preacher opens the epistles and reads them aloud. This is always the truth.

But that's just it. At the Lot 49 auction, the crier clears

his throat but doesn't get to open his mouth, open and read aloud from

the epistles (testaments mailed by the apostles), or reveal the truth.

He's interrupted or silenced by Pynchon's narrator, or perhaps by

Pynchon himself, who has given out, given up, or dropped the ball

("Keep it bouncing," Pierce, "talking business," had once told Oedipa,

"that's all the secret [is], keep it bouncing"). The last word is "END,"

not "THE END," not "TO BE CONTINUED" (which would have more "bounce"). Just END, no bounce at all.

And so, despite the post card-like "economy" of the narration, and despite the (implicit) promise to "deliver," nothing

gets confirmed, decided or resolved. The reader has waited until the

end, only to find that, in the end, more waiting (an "afterlife")

awaits. All four symmetrical possibilities remain in play, cancelling

each other out. Or, rather, the whole "lot" of them have been cancelled,

but not redeemed ("made good"); they've been addressed and stamped (Lot 49 on route to auction), but haven't arrived, won't ever arrive, God only knows.

-- Written by Bill Brown, 27 February 2004.

Authors cited:

Derrida, Jacques. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond,

originally published in French in 1980; translated into English by Alan

Bass and published by the University of Chicago Press in 1987.

Kaplan, Janet A. Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys, published by Cross River Press, 1988. Edition used: first paperback edition, 2000.

Pynchon, Thomas. The Crying of Lot 49, originally published by the J.B. Lippincott Company, 1966. Edition used: 19th ("Windstone") printing by Bantam, 1982.

Pynchon, Thomas. V., originally published by the J.B. Lippincott Company, 1963. Edition used: 4th printing by Bantam reprint, 1968.

Shell, Marc. The Economy of Literature, published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978. Edition used: 2d printing, 1979.

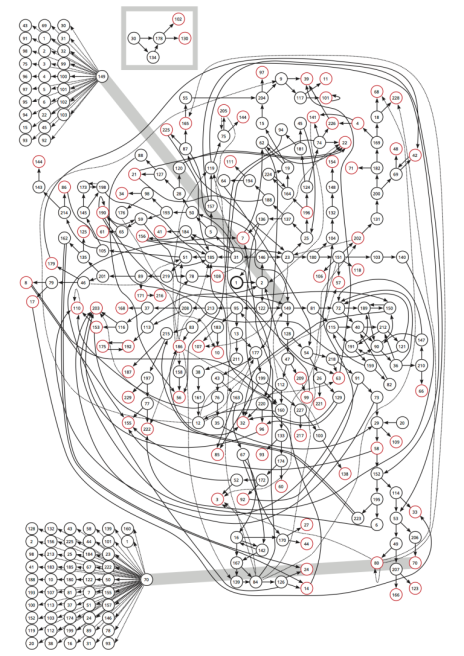

The problems with Yili-Juonikas’ experimental 650-page novel Neuromaani start already with the title. According to translator Doug Robinson, who mentions this book in an interview for The Collidescope, the ambiguous title can be translated as Neuronovel, Neuromaniac, or My Neurocountry.

Once you get past that, it gets only worse. There are at least three

degrees of inaccessibility you have to reckon with when it comes to Neuromaani.

Firstly, and most obviously, if you, like myself, don’t know Finnish,

you cannot hope to read the novel even in theory, and all you are left

with is the impressions of other people shared in a language you

understand. The second degree is applicable to you if you know the

language but have just learnt about the existence of Neuromaani.

You still won’t be able to read the novel because it is out of print

and is impossible to get in any online used bookstores. The third degree

of inaccessibility is for the lucky ones: you are not only proficient

in Finnish but also managed to buy your copy when it was still

available. But even you can’t possibly read the book in its entirety. Of

course, you can try and read all the pages from first to last, but

instead of following the story, you will be exposed to a jumble of

incoherent episodes without rhyme or rhythm. Such a stab at the

old-fashioned linear method of reading will leave you frustrated and

suffering from a headache. All you can hope for is to experience some

parts of Neuromaani by undertaking a series of non-linear journeys through the novel, making choices at the end of each chapter.

The problems with Yili-Juonikas’ experimental 650-page novel Neuromaani start already with the title. According to translator Doug Robinson, who mentions this book in an interview for The Collidescope, the ambiguous title can be translated as Neuronovel, Neuromaniac, or My Neurocountry.

Once you get past that, it gets only worse. There are at least three

degrees of inaccessibility you have to reckon with when it comes to Neuromaani.

Firstly, and most obviously, if you, like myself, don’t know Finnish,

you cannot hope to read the novel even in theory, and all you are left

with is the impressions of other people shared in a language you

understand. The second degree is applicable to you if you know the

language but have just learnt about the existence of Neuromaani.

You still won’t be able to read the novel because it is out of print

and is impossible to get in any online used bookstores. The third degree

of inaccessibility is for the lucky ones: you are not only proficient

in Finnish but also managed to buy your copy when it was still

available. But even you can’t possibly read the book in its entirety. Of

course, you can try and read all the pages from first to last, but

instead of following the story, you will be exposed to a jumble of

incoherent episodes without rhyme or rhythm. Such a stab at the

old-fashioned linear method of reading will leave you frustrated and

suffering from a headache. All you can hope for is to experience some

parts of Neuromaani by undertaking a series of non-linear journeys through the novel, making choices at the end of each chapter.

Explore

Explore