When Alan Turing and Ludwig Wittgenstein Discussed the Liar Paradox

Alan Turing attended Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ‘Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics’ in Cambridge in 1939. The following is one account of those lectures:

“For several terms at Cambridge in 1939, Ludwig Wittgenstein lectured on the philosophical foundations of mathematics. A lecture class taught by Wittgenstein, however, hardly resembled a lecture. He sat on a chair in the middle of the room, with some of the class sitting in chairs, some on the floor. He never used notes. He paused frequently, sometimes for several minutes, while he puzzled out a problem. He often asked his listeners questions and reacted to their replies. Many meetings were largely conversation.”

In relevance to this essay, Alan Turing (1912–1954) strongly disagreed with Ludwig Wittgenstein’s argument that mathematicians and philosophers should happily allow contradictions to exist within mathematical systems.

In basic terms, Wittgenstein stressed two things:

1) The strong distinction which must be made between accepting contradictions within mathematics and accepting contradictions outside mathematics.

2) The supposed applications and consequences of these mathematical contradictions and paradoxes outside mathematics.

As for 1) above, Wittgenstein said (as quoted by Andrew Hodges):

“Why are people afraid of contradictions? It is easy to understand why they should be afraid of contradictions in orders, descriptions, etc. outside mathematics. The question is: Why should they be afraid of contradictions inside mathematics?”

Wittgenstein can be read as not actually questioning the logical validity or status of these paradoxes and metatheorems. He was making a purely philosophical point about their supposed — and numerous — applications and consequences outside of mathematics. (These consequences — if not always applications — usually include stuff about consciousness, God, human intuition, the universe, human uniqueness, religion, arguments against artificial intelligence, meaning, purpose, etc.)

Thus Wittgenstein’s position on mathematical contradictions and paradoxes was largely down to his (as it has often been called) mathematical anthropocentrism. That is, to his belief that mathematics is a human invention. More concretely, in his “middle period” Wittgenstein stated that “[w]e make mathematics”; and some time later he said that we “invent” mathematics.

It can be seen, then, that Wittgenstein was clearly an anti-Platonist. Thus it’s not a surprise that he also said that

“the mathematician is not a discoverer: he is an inventor”.

Indeed the later Wittgenstein even went so far as to say that

“[i]t helps if one says: the proof of the Fermat proposition is not to be discovered, but to be invented”.

One other very concrete way in which Wittgenstein expressed his anti-Platonism was when he made the point that it’s wrong to assume that because

“a straight line can be drawn between any two points [that] the line already exists even if no one has drawn it”.

Wittgenstein consequently made the ironic comparison (which many may find ridiculous) that “chess only had to be discovered, it was always there!”.

In terms of contradictions and paradoxes again.

All the above means that if mathematics is a human invention, then any contradictions and paradoxes there are (within mathematics) must be down to… us. And if they’re down to us, then they aren’t telling us anything about the physical world (which includes Turing’s bridge — see later) or even about a platonic world of numbers — because such as thing doesn’t even exist.

Yet many of Wittgenstein’s remarks on paradoxes, Gödel's theorems, mathematical contradictions, etc. have been seen — by various commentators — as being almost (to use my own word) philistine in nature. (Much has been written on Wittgenstein’s remarks on Gödel's theorems — see here.)

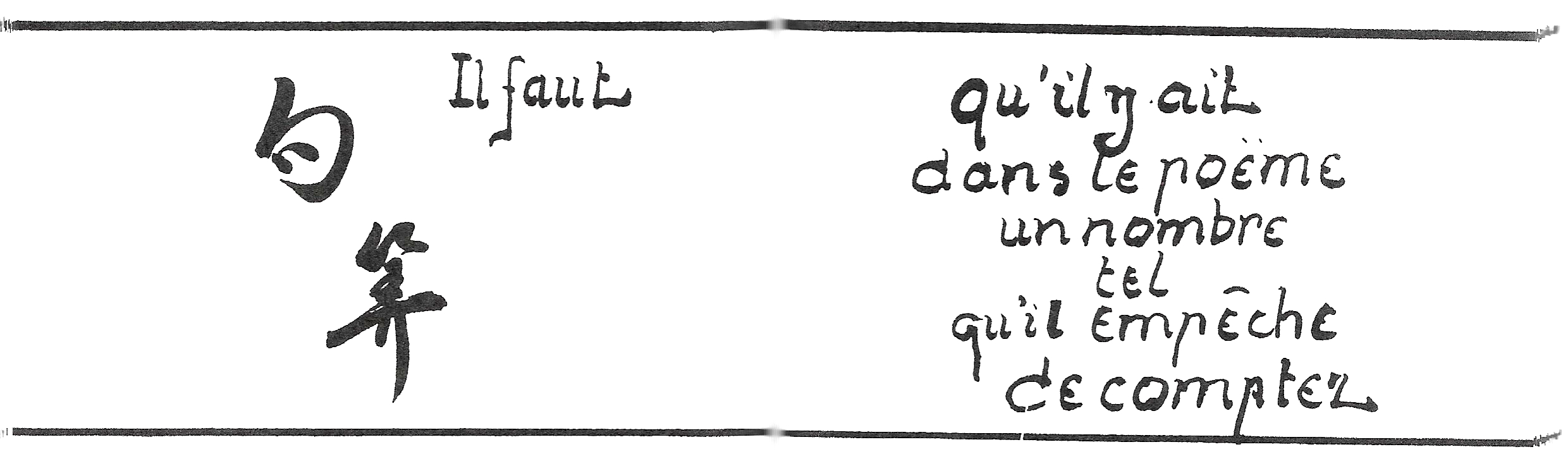

The Liar Language Game

Wittgenstein tackled the most famous of all paradoxes — the Liar Paradox. In a discussion with Turing, he said:

“Think of the case of the Liar: It is very queer in a way that this should have puzzled anyone — much more extraordinary than you might think… Because the thing works like this: if a man says ‘I am lying’ we say that it follows that he is not lying, from which it follows that he is lying and so on. Well, so what? You can go on like that until you are black in the face. Why not? It doesn’t matter. …it is just a useless language-game, and why should anyone be excited?”

At first glance it seems that Wittgenstein was perfectly correct to use the philosophical term (his own) “language-game” to refer to the Liar Paradox — as well as to many of the other paradoxes thrown up in what’s often called the foundations of mathematics. (More correctly, these paradoxes were seen to arise within various language games.) After all, the Liar paradox is internal to a language (game) which allows such a kind of self-reference. Indeed in which other language (game) would you ever find the statement, “This sentence is false”? (Even it’s supposed everyday translation - “I am a liar” — seems somewhat contrived.) These sentences simply don’t belong to everyday languages at all. Thus they must belong to a specific technical language game. (As do, for example, Gödel sentences.)

(Of course everyday language does allow other kinds of self-reference which don’t generate — obvious? — contradictions or paradoxes; such as merely referring to oneself when one says “I am happy”.)

So Wittgenstein’s position can be summed up by saying that the Liar language game doesn’t so much as display (or spot) a contradiction or paradox — it creates one.

Wittgenstein was basically stressing the artificiality of the Liar paradox. Now that artificiality doesn’t automatically mean that it has nothing to offer us. In that case, then, the word “artificiality” needn’t be negative in tone. It may simply a reference to something which is… artificial. As it is, though, Wittgenstein did mean it in an entirely negative way. After all, he said that the Liar paradox “is just a useless language-game”.

Alan Turing, on the other hand, seemed to be interested in the Liar paradox for purely intellectual reasons. (Although he will later refer to the construction of bridges.) He replied:

“What puzzles one is that one usually uses a contradiction as a criterion for having done something wrong. But in this case one cannot find anything done wrong.”

In basic terms, Turing was arguing that, unlike many other cases of contradiction, the Liar paradox doesn’t simply uncover a contradiction: it makes it the case that both x and not-x must be accepted. That is, when a (Cretan) liar utters “I am lying”, and it leads to it being interpreted as making the speaker both a liar and not a liar (i.e., at one and the same time), then “in this case one cannot find anything done wrong”.

One can almost guess Wittgenstein’s reply to this. He said:

“Yes — and more: nothing has been done wrong [].”

Wittgenstein’s argument (at least as it can be seen) was that the Liar paradox does indeed lead to this bizarre conclusion because — in a strong sense - it was designed to do so. That is, it is part of a language-game which was specifically created to bring about a paradox. And because it’s a self-enclosed and artificial language-game, then Wittgenstein also asked “where will the harm come” from allowing such a contradiction or paradox?

Alan Turing’s Bridge

It was said a moment ago that Alan Turing appeared to be interested in the Lair paradox for purely formal reasons. However, he did then state the following:

“The real harm will not come in unless there is an application, in which a bridge may fall down or something of that sort [] You cannot be confident about applying your calculus until you know that there are no hidden contradictions in it.”

On the surface at least, it does seem somewhat bizarre that Turing should have even suspected that the Liar paradox could lead to a bridge falling down. That is, Turing believed — if somewhat tangentially — that a bridge may fall down if some of the mathematics used in its design somehow instantiated a paradox (or a contradiction) of the kind exemplified by the Liar paradox.

Yet it’s hard to imagine the precise route from the Lair paradox to practical (or concrete) applications of mathematics of any kind — let alone to the building of a bridge and then that bridge falling down.

Indeed many (pure) mathematicians have often noted the complete irrelevance of much of this paradoxical and foundational stuff to what they do. Thus if it’s irrelevant to many mathematicians, then surely it would be even more irrelevant to the designers who use mathematics in the design of their bridges.

This metamathematics/the applications of mathematics opposition is summed up by the mathematician and physicist Alan Sokal in two parts. Firstly, Sokal stresses the difference between “metatheorems” and “conventional mathematical theorems” in the following way:

“[] Metatheorems in mathematical logic, such as Gödel's theorem or independence theorems in set theory, have a logical status that is slightly different from that of conventional mathematical theorems.”

And it’s precisely because of this substantive difference that Sokal continues in this way:

“It should, however be emphasized that these rarefied branches of mathematics have very little impact on the bulk of mathematical research and almost no impact on the natural sciences.”

So if such metatheorems have (to be rhetorical for a moment) almost zero “impact on the natural sciences”, then surely they have less than zero impact on the design of bridges.

Again, it’s hard to see how there could be any (as it were) concrete manifestation of the Liar paradox. That said, perhaps Turing’s argument is that there couldn’t be such a concrete manifestation. And that’s precisely because if there were such a manifestation — then some bridges would fall down!

So what about Wittgenstein's response to this line of reasoning?

Wittgenstein responded to Turing by saying that “[b]ut nothing has ever gone wrong that way yet”. That is, no bridge has ever fallen down due to a paradox or contradiction in mathematics.

The Principle of Explosion

As already hinted at, all the above can be boiled down to Alan Turing predicting (or simply conceiving of) concrete and design-related manifestations of what is called (by logicians) the principle of explosion.

Yet it was Wittgenstein who noted what Turing was actually getting at. He said:

“Suppose I convince [someone] of the paradox of the Liar, and he says, ‘I lie, therefore I do not lie, therefore I lie and I do not lie, therefore we have a contradiction, therefore 2x2 = 369.’…”

In other words, “from a contradiction, anything follows”. Or to put that as Wittgenstein himself put it:

If we allow the sentence

“I lie, therefore I do not lie, therefore I lie and I do not lie…”

then we must also allow this equation:

2 x 2 = 369

But in the case of 2 x 2 = 369, Wittgenstein argued that “we should not call this ‘multiplication’ at all”. And surely he was right. Yet this conclusion is seen to be a logical consequence of accepting the legitimacy of the Liar paradox.

Finally, it can also be added, in a Wittgensteinian manner, that we are free to invent a language (game) in which 2 x 2 (or, perhaps more accurately, “2 x 2”) does indeed equal 369 (or “369”)!