The New

Reprints: A Voyage of Discovery to the Golden Age of Comic Books

Part 6: DC from

the 1930s and the Originals of Marvel, Part I

This Chapter was too long so I have to present it in two parts.

This project will be presented in twelve parts. Unfortunately, I can’t change

the order, so later posts will appear first. Please try to check this out

in order! And your comments are important. Please post how you became

aware of comics and their history!

- Introduction/Comics in "real" books.

- 1960s: Reprints from the Comic Companies: 80 Page Giants

& Marvel Tales!

- 1960s: The Great Comic Book Heroes

- 1960s: The Paperback Era

- 1970s: The Comic Strips AND the Comic Book Strips!

- 1970s: DC from the 1930s and the Origins at Marvel Part I

- 1970s: DC from the 1930s and the Origins at Marvel Part II

- 1980s until Today: Horror We? How's Bayou! The EC Age of Comics

- 1990s until Today: The Archives and Masterworks

- How The West Was Lost

- When Comics Had Influence: Public Service, Education & Promotion

- Journeys End, What We Leave Behind: A Century of Comics

So let us continue our voyage to and from the

1960s and discover the world of comics once almost forgotten. Our expedition is

mostly into the world of reprints that were available OUTSIDE the

newsstands and comic book stores but we will have a few detours on the way.

While the 1970s began the earnest reprinting of comic

strips, the humble comic book was still the prodigal son who had not yet returned.

The decade began with a major event:

the comic book shot heard around the world. Jim Steranko

created and produced a remarkable two part collection of “

The History of Comics”

which was just brilliant. The super-large, black and white books, told

the story of comics in great detail, going back to their pulp

beginnings. Steranko

gave us superb images, in black and white, and told the early stories of

both DC

and Marvel. Volume 2, published in 1972,

picks up where the first volume left off, using terrific images to tell

us about

Blackhawk comics,

Plastic Man, Captain Marvel and his family. A

highlight of the second volume is a full

Spirit

story, all seven

pages. It also had a compendium of the fascinating Steranko pages from

his Marvel work. I had expected and hoped for a part 3, but it is

now 40 years later and no dice. But, in

all this time, nothing has topped this work, or the beautiful covers

created by

Steranko. And what was the price for this gorgeous huge paperback book?

$1.98.

“All in Color For a Dime” edited by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson, was published in 1972, and it featured

mostly essays that concentrated on Comic Books. Popeye, the first super-hero of them all, is also

featured. Here, in eleven chapters, authors such as Roy Thomas, Ted White and

Harlan Ellison discuss the original Captain Marvel, the war comics of the

1940s, and the second-banana heroes such as Johnny

Quick. What a great and important

read! While the book is almost all text, there is a small color section of

covers mostly from the Golden Age. The book cost $11.25 in hardcover then! Three

years later it was followed by a sequel, “The Comic

Book Book,” which covered topics such as Jack Cole and Plastic Man, Will Eisner and The Spirit, Tarzan, EC comics and Frankenstein.

|

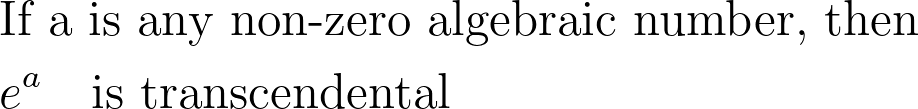

| This page is from the Color section of All in Color for a Dime.

It was important to me because I had heard that Marvel's Daredevil got

his name from this character, but I had never seen a picture of him. |

I recently asked Roy Thomas about his involvement

in “All in Color…”: “Jerry Bails sent me

Julie Schwartz's copies of the early XERO (probably #1-3), which alas were lost

in the mail when I sent them back. I

contacted the Lupoffs to get #4 forwarded, and Dick asked me to do the article about

the non-Marvel Fawcett heroes, using a few comics I had and a number that he

sent me, plus my memories... not much more.

He even gave me a title, "Captain Billy's Whiz Gang," and a

first paragraph or so of history about Fawcett, which I used virtually intact,

though he didn't seem to care to be credited for it. I was too busy when the book version was done

to revise the article at all, but I'm happy to have been a part of the

series... even though I gave Dick conniption fits with my lateness, as I related

back in AE #18. See that issue for more

quotes from me re XERO. I had to decline

being in the second book (THE COMIC BOOK BOOK), as well... I think I was

supposed to write about the "commercial" super-heroes in the old

comics, like Captain Tootsie and Volto, etc... not dissimilar to what was

eventually done in ALL-STAR COMPANION, VOL. 2.”

“Jerry Robinson’s The Comics, An Illustrated History of Comic

Art,” (1974) was a wonderful, detailed look at the

history of comic strip art, by an artist himself. This was a 250 page, highly

illustrated black and white book which had wonderful color section. It was a bit of a disappointment

in only one way, Robinson was one of the greatest and most important comic book

artists, the first to draw the Joker and Robin in the Batman

series. Yet, there isn’t a piece in here about comic books. Sigh.

Robinson discussed the artists and even the technology that

drove the art form at the beginning of the century. He divides the book into several

chapters, such as “A New Art Form.” “The Golden Age” (which for him was 1910-1919)

and the “Cavalcade of Color.” In each chapter he allows artists including,

Milton Caniff, John Hart, Leonard Starr to leave their comments about the era.

Charles Schulz: When people talk about "putting

meaning" into comic strips, too often they mean political meaning or refer to crime. In the first case, it seems

to me that the meaning is directed into too narrow an area; in the second, it

deals with something which plays a relatively minor role in the lives of most

people.

It is

surprising, therefore, that so many cartoonists working in such a marvelously

flexible medium have not dealt more closely with the real essential aspects of

life such as love, friendship, and day-to-day difficulties of simply living and

getting along with other people.

Comic strip language is notoriously simple, and, of course, this is

understandable when one considers the small space to which we are confined in

the newspaper. As strips have been reduced in size, due to newsprint shortage

and other such difficulties, dialogue has been reduced and real conversations

have all but disappeared.

Comic strip language is notoriously simple, and, of course, this is

understandable when one considers the small space to which we are confined in

the newspaper. As strips have been reduced in size, due to newsprint shortage

and other such difficulties, dialogue has been reduced and real conversations

have all but disappeared.

Lack of

space, however, is not the only reason for this. I believe that a more

important reason is simply a lack of desire and imagination. One of the most

delightful aspects of life is conversation. Talking with a new friend,

discovering new ideas, and learning about each other can be one of the great

experiences of life.

Good writers know this and make use of it in other

media. I have been trying to introduce this into the Peanuts strip for the past several years because I feel it is an

area that has not been well cultivated.

Dark Horse, in 2011 published an updated and totally redone version of this book. of this one entitled, “Jerry

Robinson’s The Comics, An Illustrated History of Comic Art 1895-2010.” Wow, this a very different book, in

full color throughout. There is so much added, including the strips that gained

popularity since the first addition such as Doonesbury. Robinson, in the second edition also touches

on certain themes that were taboo in the past, such as the integration of

comics, an important subject.

After Robinson's volume, comic books would no longer be dismissed. Pierre Couperie’s “A History of the Comic Strip”

(1968), was written with Maurice Horn. This book doesn’t just reference

comic strips that were

American, it acknowledges and explains the European influence on the

media. This

had been ignored in most other books, including the ones I presented in

the

introduction. For some reason, the progression of comic illustrated

storytelling

is most often presented as a totally American art form, and creators

consistently looked to England to have their

efforts validated partially because of an inferiority complex and

because Europe had developed their own comics. To fully understand the

evolution comic

books this book takes us to the mid 1800s. Rodolphe Topffer, a

Frenchman, was an early innovator

of the

comic strip and he was able to foresee the future: the “comic book” and

the “graphic novel:” In describing the comic book as a novel he wrote:

“The drawings

without their text, would have only a vague meaning; the text, without the

drawings, would have no meaning at all. The combination of the two makes a kind

of novel, all the more unique in that it is no more like a novel than it is like

anything else.”

Topffer understood that the drawings and the text must be

symbiotic. Some may dispute this, but it makes no difference whether the text

is in balloons or at the bottom of the page. What is important is that they are

dependent on each other, not where they are placed.

|

| This scan is from

"Rodolphe Topffer, The Complete Comic Strips" Compiled, Translated and

Annotated by David Kunzle. University Press of Mississippi, 2007. $65 on

Amazon |

|

|

|

|

Les Daniels authored,“

Comix, A

History of Comic Books in America”

in 1971. By today’s standards, this would not be considered great

reprint book. It is

in black and white, with a small color section, and the comic pages

printed

two on a page that had to be turned 90 degrees to read. But it was truly

a gold mine then of Golden Age material. Daniels fully discusses the

history of comic BOOKS. Of course, he leads

off with what will become the obligatory essay on the

Yellow

Kid (featured at the beginning of all books about comics), but he swiftly gets into

Superman, comic books and the Golden Age.

He doesn’t just discuss the well known characters such as

Batman, but he discusses

Blackhawk and Chop-Chop,

The Spirit and Ebony

, Captain Marvel

and Steamboat Willie, and many others. Daniels

writes about the genre of Funny Animals, which he calls Dumb Animals,

and the 1960s and 1970s Underground comics. He also examines EC comics

and crime comics, such as Lev Gleason’s “

Crime Does Not Pay” that

led up to them. The book contains many stories and, finally, a

Crime Does Not

Pay tale is one of them.

Daniels writes: “Gleason

and Biro also brought a new and very controversial slant to comic books with

Crime Does Not Pay. Beginning in 1942, this comic book featured factual

accounts of conflicts between criminals and the law. In a broad sense, this was

the same theme the superheroes had explored. Conflict is, after all, the basis

of plot, but Crime Does Not Pay, minus the fantasy element, really sharpened

the impact. The tone was sternly, even dogmatically realistic, and grim details

were never lacking. The story reprinted here, "Baby Face Nelson vs. The U.

S. A." (No. 52, June 1947) represents this publication during its period

of greatest popularity. The artwork is by George Tuska. It seems certain that

the intention of this comic book was sincere; certainly its new approach was

successful, as it gained huge circulation during the postwar years. Perhaps as

a result of the mixed emotions it inspired, perhaps because comic books had

been around long enough to gain general recognition, there were rumbling

resentments against the industry as a whole.”

|

| These are not two pages put together by me, this is how the pages were printed, two on a sheet. |

Daniels then looks at the aftermath of the Comics Code and discusses how publishers tried to reinvent adult comics with Humbug and the Warren Publications titles of Creepy and Eerie. It would take until 2009 for

Humbug to be reprinted. Creepy, which was widely available in the 1960s, began being reprinted in 2008 by Dark Horse.

On the left is a copy of the original

page from Humbug #9, 1958. The image on the right is from the Humbug

book from Fantagraphics, 2009.

This is as good a place as any to bring up this point. I

know many of us are collectors and having the originals is a good thing. Many originals are worth a lot of money. But keeping and reading the reprint books

do have a few advantages:

- Often, the reprint

books are clearer, sharper and just plain easier to read.

- All the issues are in one

place.

- The books are not fragile

like old comics. Old comics also may lose some value with use and they tear

and stain easily.

- They are cheaper

than buying the originals. Further, if you like the comics and want to

keep them to read, keep the reprints and sell the comics! Of course, for collectors,

you’d only sell the comics you are not attached to.

- Many dealers have told us that when a Masterwork or reprint comes out the comis in those titles go down greatly in value.

Oh, yes, there is a chapter on Marvel!

Sadly, Les Daniels died on Nov. 5, 2011, at his home in

Providence, R.I. He was 68.

I don’t want to underestimate the importance of these volumes;

they were the beginning of a long list of successful and interesting books

about COMIC BOOKS! And the Golden Age!

DC Travels from the

1930s to the 1970s

Bonanza Publishing published four books in 1971 that

finally brought us back to the Golden Age of

Superman, Batman, and Captain Marvel (Shazam). These three had volumes

released which presented stories “From The 30s to the 70s.” Superman and Batman were DC characters;

Captain Marvel was a creation of Fawcett Publications, purchased by DC. What a

treasure it was to get these books! The

volumes contained stories that were spread out over 30 years, mostly in black

and white. There were some color features, (“36 Pages in Full Color”), but these older

stories were just wonderful. The books presented many of the origin stories, not

just of the heroes, but also of the villains such as the Joker, and the supporting

characters, such as Alfred the butler. Some of the tales in the Batman volume (including his first appearance from Detective Comics #27, as well as the Alfred story

referred to above) were reprints from anniversary and 80 page

giant issues from the '60s, which had been traced from their original Golden

Age printings.

The introductions, all by E. Nelson Bridwell, were very

interesting. Perhaps the most compelling part of the books was to see how the

characters changed, especially after the Comics Code was introduced. Batman, for example, became less dark and the stories

got lighter. Superman became less of a wise-guy and more interplanetary.

|

This was an important reprint. If you recall I wrote in chapter 3, The Great Comic Book Heroes that a lawsuit had prevented anyone from printing the Origin of Captain Marvel, or any other of his marvel tales.

Finally, I get to read his complete origin! |

All in color for $11. Bonanza Books in 1976 also gave

us

“Secret Origins of the Super DC Heroes.” At

first glance, I was happy to see another book that had Golden Age stories in

it. Sadly, there were far too many Silver Age origin stories, including

Superman from 1975. Many of the Golden

Age origins, including the ones of the

Flash, Green Lantern, Superman, Plastic Man, Captain Marvel

and Batman had shown up in other reprints, including the

The Great Comic Book Heroes. This book of secret origins had previously “unreprinted” stories

from

Batman #47, and the Golden Age origins of

Green Arrow, Hawkman and the Atom. Carmine Infantino wrote the introduction.

When published, these were the only Golden Age reprints available in

bookstores. They were placed in the "Humor" section. And, with two

exceptions, it would remain that way for the rest of the decade.

The next book of Golden Age reprints to be found in bookstores during

the 1970s was probably more famous for its introduction than its

stories. Gloria Steinem, a leader for the civil rights for women, wrote

the

introduction to Wonder Woman, typing her into

the ongoing “woman’s movement.” She wrote that Wonder

Woman “symbolizes many of the values of the woman’s culture that

feminists are now trying to introduce into the mainstream.” Ms. Steinem never mentions bondage as one of

their goals.

Here's another small detour from the book store. By the mid 1970s, Comic Book Stores were

becoming common. Soon there would be 10,000 of them, now we have less than 3,000. Since they had

more space for comic book related material, more reprint comics began to come

out. Marvel was now regularly publishing,

Where

Monsters Dwell, Beware and other comics featuring stories from

their 1950s Atlas Era. By the mid 1970s about 25% of Marvel’s output

were reprints. None were from their Golden

Age of the 1940s.

As the new Comic Books stores opened they all had their own price lists,

which

would later be called price guides. These lists were rexographed or

mimeographed using the cheapest forms of reproduction available at the

time. The lists were not

made to last long, their inventory and pricing changed almost daily.

Their lists became invaluable, revealing important information!

In 1979 and 1980 DC gave us a taste of the Golden Age with

three trade paperbacks: America and War,

Mysteries in Space and Heart Throbs. These comics feature the “best” of

war, science fiction and romance comics respectively. The volumes also featured

complete checklists for their respective genres.

Not all the stories were from the Golden Age of the 1940s

and early 1950s, some were Silver Age Tales.

But we are running out of space, so I have to divide this topic into two

chapters. Too bad, I won't have the space to explain the importance of

the next two panels to our voyage of discovery until next time.

Or how a few stamped, self-addressed envelopes began to uncover the mysteries of the Golden Age.

Things are really beginning to heat up now, Barry. Roll on the next instalment. I'm surprised you haven't had more comments about these labours of love, but I'm sure your readers are appreciating them none-the-less.

ReplyThanks Kid, and thanks for you help again.

ReplyI notice people respond on other sites, I guess they are shy about responding here. I am very interested in finding our about their experiances, especailly those in other countries.

Wonderful. The original Steranko history, though, did not have the title on the cover. That was added for later printings.

I just recently sold my copy of the Batman volume. Never had or even saw the Wonder Woman or Secret Origins volumes.

I can't tell you how influential ALL IN COLOR...was for me! I was able to tell Dick Lupoff a few years back though, and Don Thompson some years before that.

Here's a piece I published 6 years back on a few of my influences. http://booksteveslibrary.blogspot.com/2006/01/comic-book-books.html